Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity: What It Is and How to Manage It

Understanding symptoms, mechanisms, and practical strategies when celiac disease is ruled out

Many people experience clear and reproducible symptoms after eating gluten despite negative celiac testing—an experience that often leaves them confused, dismissed, or without clear clinical direction. When standard labs come back “normal,” symptoms such as bloating, fatigue, brain fog, joint pain, or headaches are frequently attributed to stress, IBS, or nonspecific food intolerance rather than a distinct physiological response.

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity (NCGS) describes a biologically mediated reaction to gluten that occurs without the autoimmune intestinal damage characteristic of celiac disease. Although once controversial, NCGS is now recognized as a condition that can affect digestive function, immune signaling, and neurological health through mechanisms that differ from classic autoimmunity.

Unlike celiac disease, NCGS does not involve villous atrophy or positive celiac antibodies. However, symptoms can still be persistent, systemic, and disruptive, often continuing for years while individuals cycle through testing, elimination diets, and unanswered questions after conventional evaluations come back normal (1).

This article examines what non-celiac gluten sensitivity is, how it differs from celiac disease, the mechanisms believed to drive symptoms, and practical, evidence-informed strategies for identifying and managing gluten sensitivity within a broader gut and immune health framework.

Celiac Disease vs. Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

How Celiac Disease and Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Differ

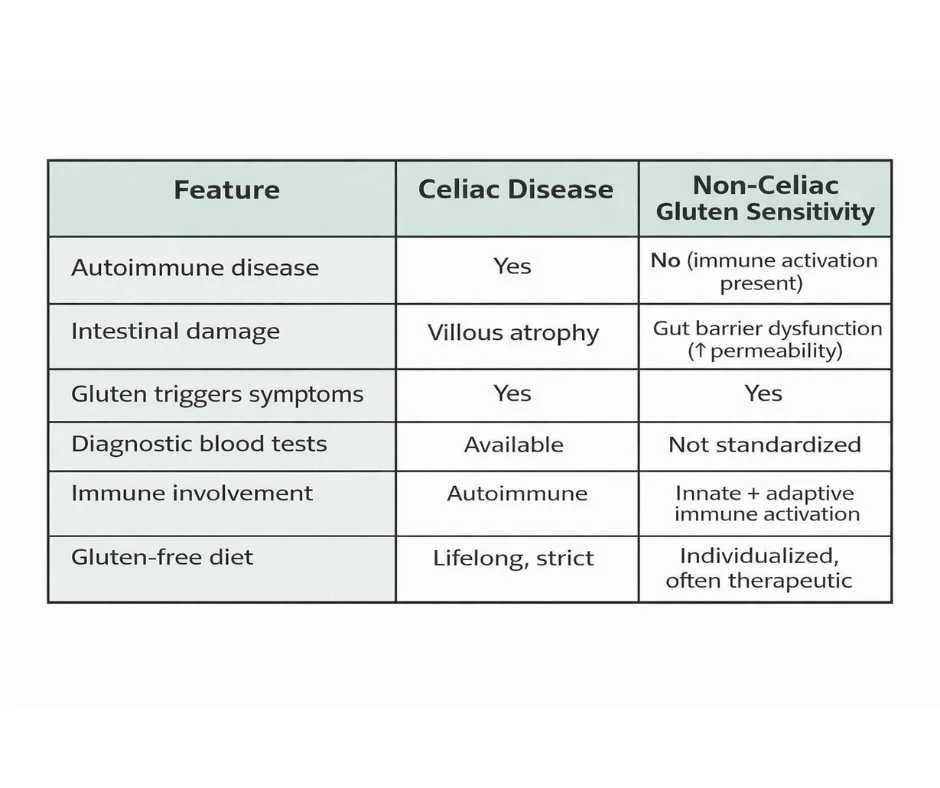

Celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity are both triggered by gluten exposure, but they involve fundamentally different immune mechanisms and clinical consequences.

Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition in which gluten ingestion triggers an immune attack on the lining of the small intestine, leading to villous atrophy, malabsorption, and measurable autoimmune markers. Diagnosis is supported by specific antibodies and confirmed by intestinal biopsy when gluten exposure is ongoing (2).

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity, by contrast, causes symptoms without autoimmune destruction of intestinal tissue. Individuals with NCGS do not develop villous atrophy or classic celiac antibodies, yet they may still experience significant digestive, neurological, musculoskeletal, and inflammatory symptoms following gluten exposure.

Proposed Mechanisms Behind Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Although NCGS does not meet criteria for autoimmune disease, current research indicates that it is not a benign or imaginary condition. Evidence suggests NCGS may involve:

Immune activation without autoimmunity

Alterations in gut microbiome composition

Increased intestinal permeability following gluten exposure

These mechanisms help explain why individuals with NCGS can experience systemic symptoms—including brain fog, fatigue, joint pain, headaches, and skin reactions—even in the absence of visible intestinal damage.

Why the Difference Between Celiac Disease and NCGS Matters Clinically

Understanding the distinction between celiac disease and non-celiac gluten sensitivity is critical. Individuals with NCGS may be incorrectly reassured when celiac testing is negative, despite ongoing symptoms that reflect immune activation and gut barrier dysfunction.

Recognizing NCGS as a distinct clinical pattern helps shift the focus away from dismissing symptoms and toward identifying the physiological processes driving them—an essential step for appropriate evaluation and management.

Common Symptoms of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Why Symptoms of Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Are Often Delayed

Symptoms of non-celiac gluten sensitivity are often delayed, variable, and systemic, appearing hours to days after gluten exposure rather than immediately (3–5). This delayed response is one of the primary reasons NCGS is frequently overlooked or misattributed to unrelated conditions.

Because reactions are not immediate or consistent, individuals may struggle to connect symptoms to gluten intake, particularly when digestive symptoms are mild or absent.

Symptom Patterns Associated With Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity can affect multiple systems simultaneously. Common presentations include:

Bloating, gas, or abdominal discomfort

Brain fog or difficulty concentrating

Fatigue or persistently low energy

Headaches or migraines

Joint or muscle pain without a clear cause

Mood changes such as anxiety, irritability, or low mood

Skin conditions including rashes, acne, or eczema

Diarrhea or constipation

Symptoms may fluctuate in severity and frequency and are not always digestive in nature. Some individuals primarily experience neurological, musculoskeletal, or immune-related complaints, while others notice a combination of systemic and gastrointestinal symptoms.

Why Pattern Recognition Matters More Than Individual Symptoms

Because reactions are often inconsistent and delayed, identifying non-celiac gluten sensitivity relies more on recognizing patterns over time than on single exposures or isolated lab results. Tracking symptom timing, intensity, and recurrence in relation to gluten intake provides more meaningful insight than focusing on individual reactions.

This pattern-based presentation underscores the importance of evaluating symptoms within their broader physiological context, rather than dismissing them when conventional testing fails to provide clear answers.

Is Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity a Real Condition?

Why Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Was Historically Questioned

For many years, non-celiac gluten sensitivity was debated due to the absence of clear diagnostic markers and the overlap of symptoms with other functional or inflammatory conditions. Without villous damage, autoimmune antibodies, or a definitive lab test, NCGS was often framed as a diagnosis of exclusion rather than a distinct physiological process.

More recent research, however, has helped clarify the biological mechanisms involved, moving non-celiac gluten sensitivity beyond speculation and toward measurable immune and gut-related changes.

What Research Shows About Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

A well-known study from Columbia University evaluated individuals who experienced reproducible symptoms with gluten exposure despite negative celiac testing. Researchers identified measurable biological changes that distinguished NCGS from both celiac disease and placebo responses (6).

Key findings included:

Increased intestinal permeability, indicating compromised gut barrier function

Low-grade immune activation, even in the absence of classic autoimmune markers

Structural epithelial cell injury following gluten exposure

Improvement in inflammatory markers after sustained adherence to a gluten-free diet

Why These Findings Matter for Clinical Care

Importantly, these changes occurred without the villous atrophy characteristic of celiac disease, helping define non-celiac gluten sensitivity as a distinct clinical entity rather than a mild or early form of celiac disease.

Together, these findings support NCGS as a biologically driven condition involving immune activation and gut barrier dysfunction, not a psychosomatic response or dietary trend. Recognizing this distinction is essential for guiding appropriate management and avoiding dismissal of persistent, pattern-based symptoms in individuals whose testing does not meet criteria for celiac disease.

The Role of Modern Wheat and Glyphosate in Gluten Sensitivity

How Modern Agricultural Practices Influence Gluten Reactivity

While wheat itself is not genetically modified, modern agricultural practices introduce additional exposures that can influence how the body responds to gluten. In conventional farming, wheat is often sprayed with glyphosate shortly before harvest to accelerate drying, a practice that can leave measurable residues in the final product.

These residues are not inherent to wheat as a plant, but rather reflect changes in how wheat is grown and processed in modern food systems.

Potential Effects of Glyphosate on Gut Barrier and Immune Function

Research suggests that glyphosate exposure may contribute to gut and immune stress through several mechanisms, including:

Disruption of gut microbiome balance

Increased intestinal permeability

Interference with digestive enzyme activity (7)

In susceptible individuals, these effects may compound gluten-related immune activation, increasing symptom severity even when gluten intake itself is relatively modest. This may help explain why some people tolerate traditionally grown or minimally processed grains more easily than modern conventionally produced wheat products.

Why Environmental Factors Can Amplify Gluten Sensitivity

Understanding this context does not imply that glyphosate is the sole cause of non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Rather, it highlights how environmental exposures can act as amplifiers, lowering tolerance thresholds and complicating recovery in individuals who already have underlying gut barrier or immune vulnerabilities.

Recognizing these contributing factors helps shift the focus away from a single-food explanation and toward a broader understanding of how modern dietary and environmental inputs interact with gut and immune health.

Why Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Should Not Be Ignored Clinically

Ongoing Immune Activation and Gut Barrier Dysfunction

Although non-celiac gluten sensitivity does not cause the villous destruction seen in celiac disease, continued gluten exposure in sensitive individuals can perpetuate intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation (8,9). When the gut barrier remains compromised, immune-stimulating particles gain repeated access to circulation, sustaining low-grade inflammatory signaling.

Over time, this pattern places ongoing demand on immune regulatory systems. In individuals with genetic susceptibility or significant environmental stressors, repeated immune activation through a compromised gut barrier may contribute to immune dysregulation rather than resolution (10).

Links Between Gut Permeability, Gluten Sensitivity, and Autoimmune Conditions

Chronic immune activation associated with increased intestinal permeability has been linked to a higher risk of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions. Research has associated this mechanism with disorders such as:

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

Rheumatoid arthritis

Psoriasis

Lupus

Type 1 diabetes

Importantly, these associations do not suggest that non-celiac gluten sensitivity directly causes autoimmune disease. Rather, they highlight how ongoing gut barrier dysfunction and immune stimulation can act as contributing factors in susceptible individuals.

Why Early Recognition of Gluten Sensitivity Matters

Understanding this connection helps explain why symptoms of non-celiac gluten sensitivity often extend beyond digestion and why addressing gluten reactivity can be an important component of long-term immune and metabolic health—even in the absence of celiac disease.

Recognizing and addressing NCGS early allows for intervention before persistent immune activation becomes entrenched, supporting more stable gut barrier function and healthier immune regulation over time.

How Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Is Identified Clinically

There is currently no single diagnostic blood test that confirms non-celiac gluten sensitivity. Instead, identification relies on a combination of clinical history, symptom patterns, targeted testing when appropriate, and dietary response over time.

Because symptoms are often delayed and systemic, context matters. Patterns related to gluten exposure, symptom timing, and response to removal are frequently more informative than isolated lab values viewed on their own.

The Role of Targeted Testing in Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

In some cases, specialty testing can help clarify whether gluten is acting as a meaningful contributor to symptoms rather than relying solely on trial-and-error.

When used thoughtfully, this type of testing may help evaluate:

Intestinal permeability, which reflects gut barrier integrity

Immune reactivity to gluten and wheat proteins, even in the absence of celiac disease

Cross-reactive food responses that may perpetuate inflammation despite gluten avoidance

Importantly, these tests are not diagnostic in isolation. Their value lies in how results are interpreted alongside symptoms, clinical history, and dietary response rather than as standalone answers.

Gluten Elimination and Reintroduction as a Clinical Tool

A structured elimination of gluten can be a valuable approach for identifying non-celiac gluten sensitivity once celiac disease has been ruled out. In this process, gluten is removed consistently and completely for a defined period—often several months—to allow inflammatory signaling to settle and the gut barrier to stabilize.

During the elimination phase, attention is paid not only to obvious sources of gluten, but also to hidden gluten and cross-contamination, which can otherwise obscure results. Symptom patterns, energy levels, digestive function, skin changes, and immune-related responses are tracked over time rather than day-to-day fluctuations.

Reintroduction is done deliberately and in isolation. Gluten is reintroduced in a controlled manner while other variables remain stable, allowing symptoms to be assessed over several days. Because delayed reactions are common, careful observation over time is often more informative than immediate responses alone.

When performed correctly, this process can provide meaningful insight into whether gluten is acting as a primary trigger, a compounding factor, or is unlikely to be clinically relevant for a given individual. For many people, guidance during this process helps avoid unnecessary long-term restriction while ensuring accurate conclusions.

Gluten Cross-Reactive Foods and Immune Reactivity

Why Symptoms May Persist Despite a Gluten-Free Diet

Some individuals continue to experience symptoms even after removing gluten completely. In these cases, ongoing symptoms may be driven by immune cross-reactivity—a process in which the immune system responds to proteins that share structural similarities with gluten.

When cross-reactivity is present, the immune system may interpret certain non-gluten foods as gluten-like, triggering inflammatory signaling despite strict gluten avoidance. This can create the impression that a gluten-free diet is “not working,” when in reality, additional dietary triggers are continuing to activate the immune response.

Common Gluten Cross-Reactive Foods

Cross-reactivity is highly individual and does not affect everyone with non-celiac gluten sensitivity. However, foods that are more commonly reported as cross-reactive for some individuals include:

Dairy proteins

Corn

Oats, including some products labeled gluten-free

Coffee

Rice

Eggs

Certain grains and seed-based foods

The presence of these foods in the diet does not automatically indicate a problem. Their relevance depends on individual immune response, gut integrity, and overall inflammatory burden.

Why Individualized Evaluation Is Essential for Gluten Sensitivity

Not everyone with non-celiac gluten sensitivity reacts to cross-reactive foods, and unnecessary long-term restriction can create additional nutritional and metabolic stress. Identifying whether cross-reactivity is truly relevant helps reduce persistent inflammation, supports gut barrier repair, and prevents avoidable dietary limitation when these foods are well tolerated.

This is one reason a structured, personalized approach is often more effective than broad elimination alone, allowing dietary strategies to be tailored based on actual physiological response rather than assumptions.

Managing Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity Long Term

Non-celiac gluten sensitivity can be managed effectively with a structured, individualized approach that addresses both symptom triggers and the underlying factors affecting gut and immune resilience. Management is not limited to food avoidance alone, but focuses on reducing overall inflammatory burden while supporting long-term stability.

Foundational Strategies for Managing Gluten Sensitivity

Effective management strategies often include:

A whole-food–based gluten-free diet that emphasizes minimally processed foods rather than packaged gluten-free substitutes

Careful attention to hidden sources of gluten and cross-contamination, which can perpetuate symptoms despite strict avoidance

Nutritional strategies to prevent deficiencies that may arise with dietary restriction

Targeted support for gut barrier integrity to help reduce ongoing immune activation

Stress and nervous system regulation, which plays a meaningful role in gut permeability and immune balance

These strategies work best when applied consistently and adjusted based on individual response rather than rigid rules.

Moving From Dietary Restriction to Long-Term Gut Resilience

When approached thoughtfully, management moves away from strict or fear-based dietary restriction and toward long-term resilience. Supporting gut barrier repair, immune regulation, and nervous system balance allows symptoms to stabilize over time and helps prevent repeated flare–restrict cycles.

This framework supports a more sustainable relationship with food and health while allowing the gut and immune system the opportunity to regain balance.

Personalized Care for Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Persistent symptoms deserve thoughtful evaluation. Clarifying whether gluten is a primary trigger—or one component of a broader pattern involving gut barrier function, immune regulation, and environmental stressors—can make care more effective and sustainable.

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, support is grounded in identifying what is driving ongoing symptoms rather than relying on trial-and-error restriction alone. Care is individualized to address the specific factors contributing to gluten sensitivity and impaired gut resilience.

→ Gut Health & Digestive Restoration

When symptoms persist and answers remain unclear, a brief conversation can help bring direction and next steps into focus.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Non-Celiac Gluten Sensitivity

Is non-celiac gluten sensitivity a real medical condition?

Yes. Although non-celiac gluten sensitivity was debated for many years, research now demonstrates measurable biological changes in affected individuals, including immune activation and increased intestinal permeability after gluten exposure. These findings support NCGS as a biologically mediated condition rather than a psychosomatic response.

How is non-celiac gluten sensitivity different from celiac disease?

Celiac disease is an autoimmune condition that causes immune-mediated damage to the intestinal villi. Non-celiac gluten sensitivity does not cause villous atrophy or meet criteria for autoimmune disease, but it can still trigger immune activation, gut barrier dysfunction, and systemic symptoms.

Can non-celiac gluten sensitivity affect long-term health?

When gluten exposure continues in sensitive individuals, ongoing intestinal permeability and immune activation may contribute to chronic inflammation. Over time, this pattern may increase the risk of immune dysregulation, particularly in genetically or environmentally susceptible individuals.

Is there a test for non-celiac gluten sensitivity?

There is no single standard diagnostic blood test. Identification relies on clinical history, dietary response, and—when appropriate—specialty testing that evaluates gut barrier integrity, immune reactivity to gluten, or food cross-reactivity.

How soon do symptoms appear after eating gluten?

Symptoms may appear within hours or be delayed for one to several days. Delayed reactions are common in non-celiac gluten sensitivity, which is why pattern recognition over time is often more informative than immediate responses alone.

Why do symptoms sometimes persist even after going gluten-free?

In some individuals, immune cross-reactivity, hidden gluten exposure, gut barrier dysfunction, or ongoing stress and inflammation can continue to trigger symptoms despite gluten avoidance. This is why a structured and individualized approach is often necessary.

Does non-celiac gluten sensitivity always require lifelong gluten avoidance?

Not necessarily. Some individuals require long-term avoidance, while others may improve tolerance over time as gut integrity and immune regulation are restored. This varies based on individual biology, triggers, and overall health context.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Nature Reviews Immunology – Celiac disease and transglutaminase 2: post-translational antigen modification and HLA-associated autoimmunity

Gastroenterology – Nonceliac gluten sensitivity

BMC Gastroenterology – Spectrum of gluten-related disorders: clinical and diagnostic aspects

Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology – Effects of gluten on skin and hair: a systematic review

Nutrients – Gluten-induced neurocognitive impairment

Gut – Intestinal cell damage and systemic immune activation in individuals with self-reported wheat sensitivity

Interdisciplinary Toxicology – Glyphosate exposure and its role in celiac disease and gluten intolerance

Gut – Gliadin-induced intestinal permeability mediated by zonulin and CXCR3 signaling

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology – Microbial translocation across the gastrointestinal barrier

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Fatty acid-binding proteins as circulating markers of intestinal and tissue injury