Functional Medicine for Depression: Understanding Root Causes Beyond SSRIs

How stress physiology, inflammation, gut–brain signaling, nutrient status, environment, and genetics influence depression beyond serotonin

Depression is often described as a problem of brain chemistry—most commonly framed as a deficiency of serotonin or other neurotransmitters. This narrative has shaped decades of mental health treatment and has contributed to the widespread use of antidepressant medications, particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs).

For some individuals, this approach provides meaningful symptom relief. For many others, however, depressive symptoms persist, recur, or only partially improve despite appropriate medication use. Fatigue, low motivation, brain fog, sleep disruption, anxiety, digestive issues, chronic pain, and inflammatory conditions frequently coexist—suggesting that depression rarely develops in isolation.

Research increasingly shows that depression is not a single disease with a single cause. Instead, it reflects the cumulative effects of stress physiology, immune activation, metabolic strain, gut–brain communication, nutrient availability, environmental exposures, and individual biological vulnerability. Changes in neurotransmitter signaling often represent downstream effects of these processes rather than the original source of imbalance.

Functional medicine approaches depression through this broader physiological lens. Rather than focusing solely on symptom suppression, it seeks to understand why depressive symptoms developed and which underlying systems are contributing to ongoing dysregulation. This perspective does not reject conventional care or medication use. Instead, it recognizes that sustainable improvement often requires identifying and addressing upstream contributors that influence brain function, emotional regulation, and resilience over time.

This article explores why depression is rarely “just a chemical imbalance,” why antidepressants may not fully resolve symptoms on their own, and which biological systems are most commonly involved. Treatment strategies are addressed separately to ensure clarity, accuracy, and individualized care rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

How Depression Is Typically Treated in Conventional Medicine

In conventional healthcare settings, depression is primarily diagnosed based on symptom patterns and severity rather than underlying biological drivers. Once diagnostic criteria are met, treatment typically centers on psychotherapy, pharmacologic intervention, or a combination of both. For many individuals, this approach provides meaningful symptom support—particularly during periods of acute distress.

However, this model is largely symptom-focused, meaning treatment decisions are often guided by how depression presents rather than why it developed.

The Role of Antidepressant Medications in Standard Care

Antidepressant medications—most commonly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs)—are frequently prescribed as a first-line treatment for depression. These medications are designed to increase the availability of serotonin in the brain by inhibiting its reuptake at the synapse.

Other commonly used classes include serotonin–norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), atypical antidepressants, and tricyclic antidepressants. Each class targets neurotransmitter signaling in slightly different ways, with the goal of reducing depressive symptoms such as persistent low mood, anxiety, and impaired concentration (3).

From a conventional perspective, these medications are intended to correct presumed neurotransmitter imbalances associated with depression.

When Antidepressants Can Be Helpful

Antidepressant medications can be beneficial for some individuals, particularly those with moderate to severe depression, acute symptom burden, or significant functional impairment. In certain cases, medication may reduce symptom intensity enough to allow engagement in therapy, lifestyle changes, or daily responsibilities.

Importantly, positive responses vary widely. Some individuals experience substantial improvement, others experience partial relief, and some experience little benefit or intolerable side effects. This variability reflects the biological heterogeneity of depression rather than inconsistency in the medications themselves (4).

Limitations of a Symptom-Centered Treatment Model

While antidepressants may reduce symptoms, they do not inherently explain why depression developed or why it may persist or recur. Many individuals continue to experience fatigue, low motivation, cognitive fog, sleep disruption, or emotional blunting despite medication use (5).

Additionally, antidepressants can produce side effects that affect quality of life, including gastrointestinal symptoms, weight changes, sexual dysfunction, sleep disturbance, and emotional flattening. In some cases, these effects limit long-term tolerability or adherence (6).

These limitations do not suggest that antidepressants are inappropriate or ineffective. Rather, they highlight that symptom relief does not always equate to resolution of underlying biological stressors—a distinction that becomes important when symptoms persist despite treatment.

Why Depression Often Doesn’t Fully Improve With Antidepressants Alone

Antidepressant medications are designed to modify neurotransmitter signaling, not to resolve the upstream biological conditions that influence how the brain functions over time. For some individuals, this distinction matters little—symptom relief may be sufficient. For many others, however, depressive symptoms persist, recur, or plateau despite appropriate medication use.

This pattern does not indicate treatment failure or patient noncompliance. It reflects the biological complexity of depression.

What Antidepressants Do — and What They Do Not Address

Antidepressants primarily act on neurotransmitter availability or receptor activity, most commonly involving serotonin, norepinephrine, or dopamine pathways. These mechanisms can reduce symptom severity, particularly low mood and anxiety, but they do not directly correct:

Chronic stress physiology and HPA-axis dysregulation

Ongoing inflammatory or immune activation

Disrupted sleep and circadian signaling

Metabolic instability or impaired brain energy production

Gut–brain communication disturbances

When these upstream factors remain active, neurotransmitter-focused interventions may offer only partial or temporary relief (7,8).

Why Symptom Relief Does Not Always Equal Biological Resolution

Depression often reflects an adaptive response to prolonged physiological strain. In this context, symptoms such as low motivation, emotional flattening, fatigue, or withdrawal may emerge as protective signals rather than isolated malfunctions.

Reducing symptom intensity without addressing the conditions that produced them can leave the underlying stress load unchanged. As a result, symptoms may return when medications are adjusted, stressors increase, or adaptive capacity is exceeded again (9).

Why Response to Antidepressants Varies So Widely

Clinical response to antidepressants varies significantly between individuals. Genetics, liver metabolism, gut microbiome composition, inflammatory status, nutrient availability, sleep quality, and nervous system tone all influence how medications are processed and how the brain responds to altered neurotransmitter signaling (10).

This variability helps explain why one person may experience meaningful improvement with minimal side effects, while another experiences little benefit or intolerable adverse effects. It also reinforces that depression is not a uniform condition with a uniform solution.

An Important Safety Note About Antidepressant Use

Because this article discusses antidepressant medications and their limitations, it is important to clarify the role of medical supervision. Antidepressants should never be stopped, tapered, or adjusted without guidance from the prescribing clinician or psychiatrist. Abrupt changes can disrupt neurochemical stability and may lead to withdrawal symptoms, rebound depression or anxiety, sleep disturbance, and significant mood instability.

Functional medicine approaches depression by examining the physiological context in which medications are used, including stress physiology, inflammation, metabolic health, gut–brain signaling, and environmental load. This perspective is intended to inform and support care, not to replace psychiatric oversight. Decisions regarding medication use remain individualized, coordinated with appropriate providers, and grounded in patient safety.

Why Depression Is Multifactorial — Not Just a Neurotransmitter Disorder

Depression is not a single disease with a single biological cause. It is a shared clinical outcome that can arise when multiple regulatory systems influencing brain function are placed under sustained strain. While neurotransmitters such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine are involved in mood regulation, changes in their signaling often reflect downstream effects rather than the original source of imbalance (11,12).

This broader view helps explain why depression presents differently from person to person and why responses to the same treatment can vary so widely. It also challenges the assumption that correcting one neurochemical pathway is sufficient to restore emotional regulation, motivation, and resilience.

Why Depression Rarely Exists as an Isolated Diagnosis

In clinical practice, depression frequently overlaps with other symptoms and conditions, including fatigue, anxiety, sleep disruption, digestive complaints, chronic pain, metabolic dysfunction, and cognitive fog. These patterns suggest that depression is often embedded within broader systemic dysregulation, rather than occurring in isolation.

When several regulatory systems are stressed at once, the brain may shift into a conservation or survival state—prioritizing energy preservation and threat detection over motivation, pleasure, and emotional flexibility. In this context, low mood is not a personal failure or isolated chemical error, but a biological signal that adaptive capacity has been exceeded.

How Overlapping Symptoms Point to Deeper Systemic Strain

Functional medicine focuses on identifying the shared upstream contributors that drive these overlapping patterns. Chronic stress signaling, immune activation, disrupted circadian rhythm, impaired energy production, and altered gut–brain communication can interact in ways that amplify vulnerability to depressive symptoms (13).

Rather than asking which single neurotransmitter is “low,” this approach asks why the internal environment has become unfavorable for stable brain signaling in the first place. Understanding depression as a multifactorial condition creates a more accurate framework for explaining persistence, recurrence, and variability—and prepares the ground for examining the specific biological systems involved.

Which Biological Systems Most Strongly Influence Depression

Depression develops when key regulatory systems that support brain function become strained, dysregulated, or chronically overloaded. These systems do not operate independently. Disruption in one area often amplifies stress in others, creating feedback loops that influence mood, motivation, cognition, and emotional regulation.

Understanding how these systems interact helps explain why depression is heterogeneous—and why addressing only one pathway rarely produces durable improvement.

How Chronic Stress Alters Nervous System Signaling

Chronic psychological or physiological stress places sustained demand on the autonomic nervous system and the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. While short-term stress responses are adaptive, prolonged activation can disrupt cortisol rhythms, impair feedback regulation, and alter how the brain processes threat, reward, and emotional input (14).

Over time, this dysregulation may contribute to symptoms such as emotional blunting, fatigue, impaired concentration, low motivation, and reduced stress tolerance—features commonly associated with depressive states.

How Inflammation Affects Mood and Motivation

Low-grade, chronic inflammation is increasingly recognized as a central contributor to depression. Inflammatory cytokines can interfere with neurotransmitter metabolism, shift tryptophan away from serotonin synthesis, impair dopamine-related reward pathways, and disrupt mitochondrial energy production in the brain (15,16).

This inflammatory pattern is particularly associated with depressive symptoms marked by fatigue, anhedonia, slowed cognition, and reduced motivation, even when overt infection or illness is not present.

How Gut–Brain Communication Shapes Emotional Regulation

The gut and brain communicate continuously through immune signaling, microbial metabolites, endocrine pathways, and the vagus nerve. Alterations in gut microbiome composition or intestinal barrier integrity can increase systemic inflammation and alter signaling to the brain, influencing mood and stress responsiveness (17).

Importantly, gut-driven inflammatory signaling can affect emotional regulation even in the absence of obvious digestive symptoms, making gut–brain disruption an underrecognized contributor to depression.

How Metabolic and Mitochondrial Stress Affects Brain Function

The brain is one of the most energy-demanding organs in the body. Stable mood and cognitive function depend on consistent glucose availability, effective insulin signaling, and efficient mitochondrial energy production.

When metabolic regulation is impaired—through blood sugar instability, insulin resistance, or mitochondrial dysfunction—the brain may experience intermittent energy stress. This can manifest as irritability, brain fog, emotional volatility, low motivation, or depressive lows (18).

The Five Most Common Root Causes of Depression in Functional Medicine

While depression can arise through many biological pathways, clinical patterns tend to cluster around a small number of recurring upstream contributors. Functional medicine refers to these as root causes—not because they are the only factors involved, but because they repeatedly place sustained stress on the systems that regulate mood, motivation, and emotional resilience.

Identifying these root causes helps explain why depression often persists despite symptom-focused treatment and why individuals with the same diagnosis may respond very differently to the same intervention. These contributors frequently interact, amplifying one another over time and altering the internal physiological environment in which brain signaling occurs.

How Chronic Stress and HPA Axis Dysregulation Contribute to Depression

Chronic stress—whether psychological, emotional, inflammatory, or metabolic—places continuous demand on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Over time, this can disrupt normal cortisol signaling patterns, impair negative feedback regulation, and alter coordination between the brain, adrenal glands, and peripheral tissues (19).

As this dysregulation progresses, downstream effects extend beyond stress hormones alone. Altered cortisol rhythms influence sleep architecture, immune signaling, glucose regulation, and neurotransmitter turnover, all of which affect brain function. Rather than producing constant anxiety alone, prolonged stress dysregulation is frequently associated with fatigue, emotional flattening, reduced motivation, impaired concentration, and diminished stress tolerance—hallmark features of depressive states. In this context, depression reflects a nervous system operating under sustained adaptive strain rather than an isolated mood disturbance.

How Gut Dysbiosis and Intestinal Permeability Affect Mood

The gut plays a central role in immune regulation, neurotransmitter precursor metabolism, and inflammatory signaling. Disruptions in gut microbiome balance (dysbiosis) or increased intestinal permeability can elevate systemic inflammatory load and alter gut–brain communication via immune mediators, microbial metabolites, and autonomic pathways (20).

When this signaling becomes chronic, inflammatory cytokines and metabolic byproducts can interfere with neurotransmitter synthesis, stress hormone regulation, and mitochondrial energy production in the brain. These effects may occur even in the absence of prominent digestive symptoms, which is why gut-related contributors to depression are often overlooked in conventional mental health models. Mood changes, fatigue, or cognitive symptoms may be the most visible downstream expression of gut–immune dysregulation.

Which Nutrient Deficiencies Are Most Commonly Linked to Depression

The brain requires a steady supply of specific nutrients to support neurotransmitter synthesis, methylation pathways, antioxidant defense, and mitochondrial energy production. Deficiencies in nutrients such as B vitamins, vitamin D, magnesium, iron, zinc, and omega-3 fatty acids have been repeatedly associated with depressive symptoms (21).

When nutrient availability is insufficient, the brain compensates by prioritizing essential survival functions over higher-order processes such as emotional regulation, cognitive flexibility, and stress resilience. Nutrient insufficiencies may result from poor intake, impaired absorption, chronic stress, inflammation, medication use, or increased metabolic demand, and they often coexist rather than occur in isolation. Over time, this cumulative depletion can reduce the brain’s capacity to maintain stable mood and adaptive response.

How Environmental and Inflammatory Exposures Influence Brain Health

Environmental exposures—including mold toxins, heavy metals, air pollutants, and chemical contaminants—can activate persistent immune and inflammatory responses that affect the brain. These exposures may disrupt neurotransmitter signaling, impair mitochondrial function, and compromise blood–brain barrier integrity, increasing neuroinflammatory burden (22).

In susceptible individuals, ongoing low-level exposure can maintain a background inflammatory state that interferes with emotional regulation, motivation, and cognitive clarity. Because these exposures are often chronic, cumulative, and not immediately apparent, their contribution to depressive symptoms is frequently unrecognized, particularly when standard evaluations focus only on neurotransmitters or mood scales.

How Genetics Increase Risk Without Determining Outcomes

Environmental exposures—including mold toxins, heavy metals, air pollutants, and chemical contaminants—can activate persistent immune and inflammatory responses that affect the brain. These exposures may disrupt neurotransmitter signaling, impair mitochondrial function, and compromise blood–brain barrier integrity, increasing neuroinflammatory burden (22).

In susceptible individuals, ongoing low-level exposure can maintain a background inflammatory state that interferes with emotional regulation, motivation, and cognitive clarity. Because these exposures are often chronic, cumulative, and not immediately apparent, their contribution to depressive symptoms is frequently unrecognized, particularly when standard evaluations focus only on neurotransmitters or mood scales.

Why Depression Can Persist or Return Even After Treatment

Depression often improves with treatment, yet many individuals experience incomplete relief, relapse, or fluctuating symptoms over time. This pattern is not unusual and does not necessarily indicate treatment failure. Instead, it reflects the distinction between symptom suppression and physiological stability.

When the biological conditions that contributed to depression are only partially resolved, symptom improvement may remain fragile. In these cases, depressive symptoms tend to re-emerge during periods of increased demand, rather than disappearing in a permanent or linear fashion.

How Unresolved Upstream Stressors Sustain Depressive Physiology

Treatments that focus primarily on mood symptoms can reduce distress without fully correcting the upstream conditions that originally altered brain regulation. When these underlying stressors remain active, the nervous system continues to operate under elevated load.

Over time, this sustained demand narrows the brain’s adaptive range. Emotional flexibility, motivation, and cognitive endurance become harder to maintain, particularly under additional pressure. In this context, recurrence reflects limited reserve capacity, not a return to baseline dysfunction.

Why Symptom Improvement Does Not Always Restore System Regulation

Improvement in mood does not necessarily mean that regulatory systems have returned to equilibrium. Neural signaling can become more tolerable while deeper coordination across stress response, immune signaling, circadian timing, and cellular energy production remains unstable.

This partial normalization helps explain why individuals may feel “better, but not well.” Residual symptoms such as fatigue, low motivation, cognitive slowing, or reduced stress tolerance often indicate that underlying regulation has not fully re-stabilized, even when core depressive symptoms have eased.

How Stress, Illness, and Life Transitions Trigger Relapse

Relapse most often occurs during periods that increase physiological demand rather than at random. Acute illness, sleep disruption, hormonal transitions, or sustained psychological stress all increase regulatory load at a time when adaptive capacity may already be constrained.

When demand exceeds available reserve, the systems supporting mood regulation lose stability, and symptoms can return. This explains why depression frequently follows an episodic pattern and why recurrence often coincides with identifiable stressors rather than emerging spontaneously.

Why Individual Responses Vary Over Time

Physiology is dynamic rather than fixed. Internal conditions such as inflammatory activity, nutrient availability, sleep quality, and stress exposure shift over time, altering the biological environment in which mood regulation occurs.

As this context changes, the same individual may respond differently to the same intervention at different points in life. From a functional medicine perspective, this variability reflects changes in underlying biological state—not inconsistency of treatment, effort, or diagnosis.

How Functional Medicine Approaches Depression Differently

Conventional approaches to depression are largely organized around diagnosis and symptom severity. Once criteria are met, treatment decisions typically focus on selecting a medication, a therapeutic modality, or both, with the goal of reducing symptom burden. This model can be effective for symptom management, particularly in acute or severe cases.

Functional medicine approaches depression from a different starting point. Rather than asking which treatment matches a diagnosis, it asks why the biological systems that regulate mood became dysregulated in the first place. The focus shifts from symptom classification to understanding patterns of physiological strain that influence brain function over time.

Shifting the Focus From Diagnosis to Biological Context

From a functional medicine perspective, depression is not viewed as a single disease entity but as a shared outcome that can arise from multiple underlying pathways. These pathways may involve stress physiology, immune activation, metabolic demand, gut–brain signaling, nutrient status, environmental exposures, or combinations of these factors.

This approach recognizes that two individuals with the same diagnosis may have very different contributing drivers. As a result, the goal is not to apply a uniform solution, but to clarify which systems are under the greatest strain in a given individual and how those imbalances interact.

Understanding Symptoms as Signals, Not Isolated Failures

In functional medicine, depressive symptoms are understood as signals of regulatory stress, rather than isolated chemical errors or personal shortcomings. Low mood, fatigue, reduced motivation, and cognitive slowing are interpreted in the context of how the nervous system, immune system, and metabolic systems are functioning together.

This framing helps explain why symptoms often fluctuate with sleep, illness, stress load, or hormonal changes—and why improvement may require addressing conditions outside the brain itself. The emphasis is not on suppressing symptoms, but on understanding what they reveal about underlying physiological state.

Emphasizing System Interaction Rather Than Single Targets

Functional medicine places particular emphasis on how biological systems interact. Stress signaling influences immune activity; immune activation affects neurotransmitter metabolism; metabolic instability alters energy availability in the brain; sleep disruption amplifies all of the above.

By examining these interactions, this approach aims to identify patterns that sustain depressive physiology rather than focusing on any single target in isolation. This systems-based lens is especially relevant in individuals with persistent, recurrent, or treatment-resistant symptoms.

Individualized Evaluation as a Foundation for Care

Because contributing factors vary widely, functional medicine prioritizes individualized evaluation rather than assuming a single cause. This may include careful assessment of symptom patterns, health history, lifestyle factors, and relevant biological markers to clarify where regulation has been most disrupted.

The intent is not exhaustive testing, but targeted insight—enough information to understand which systems require attention and how interventions should be sequenced to support stability rather than overwhelm.

Understanding how these systems interact provides context for how functional medicine evaluates depression at an individual level.

What Happens After Root Causes Are Identified

Identifying root causes does not immediately change symptoms. What it changes first is clarity. Once the primary sources of physiological strain are understood, depression can be evaluated in terms of system load, reserve capacity, and regulatory stability, rather than symptom severity alone.

At this stage, the focus shifts from explanation to contextual understanding—how different systems are interacting, which pressures are most dominant, and where the nervous system is operating near its threshold.

Why Sequencing Matters More Than Intensity

Physiological systems recover in sequence, not in parallel. When multiple contributors are present, addressing them all at once can increase strain rather than reduce it. Functional medicine emphasizes identifying which systems require stabilization first, particularly those that influence stress tolerance, sleep quality, metabolic regulation, and inflammatory burden.

This sequencing helps explain why interventions that are beneficial in one phase may be poorly tolerated in another. The goal is not to accelerate change, but to support stability so that adaptive capacity can expand rather than collapse under added demand.

How Biological Context Guides Next Steps

Once root causes are clarified, care decisions are informed by biological context rather than diagnosis alone. Patterns such as sleep disruption, inflammatory activity, metabolic instability, or autonomic imbalance help determine where attention is most likely to reduce overall system load.

This approach avoids assuming that depression requires the same strategy at every stage. Instead, it recognizes that effective care depends on timing, system interaction, and individual capacity for adaptation.

Why Improvement Often Occurs Gradually Rather Than Linearly

When underlying contributors are addressed, improvement often appears first in regulatory markers rather than mood alone. Sleep may stabilize, stress tolerance may increase, or energy fluctuations may become less extreme before sustained mood changes occur.

These early shifts indicate that internal regulation is improving, even if depressive symptoms have not fully resolved. Over time, as system coordination strengthens, mood stability becomes easier to maintain with less effort and less volatility.

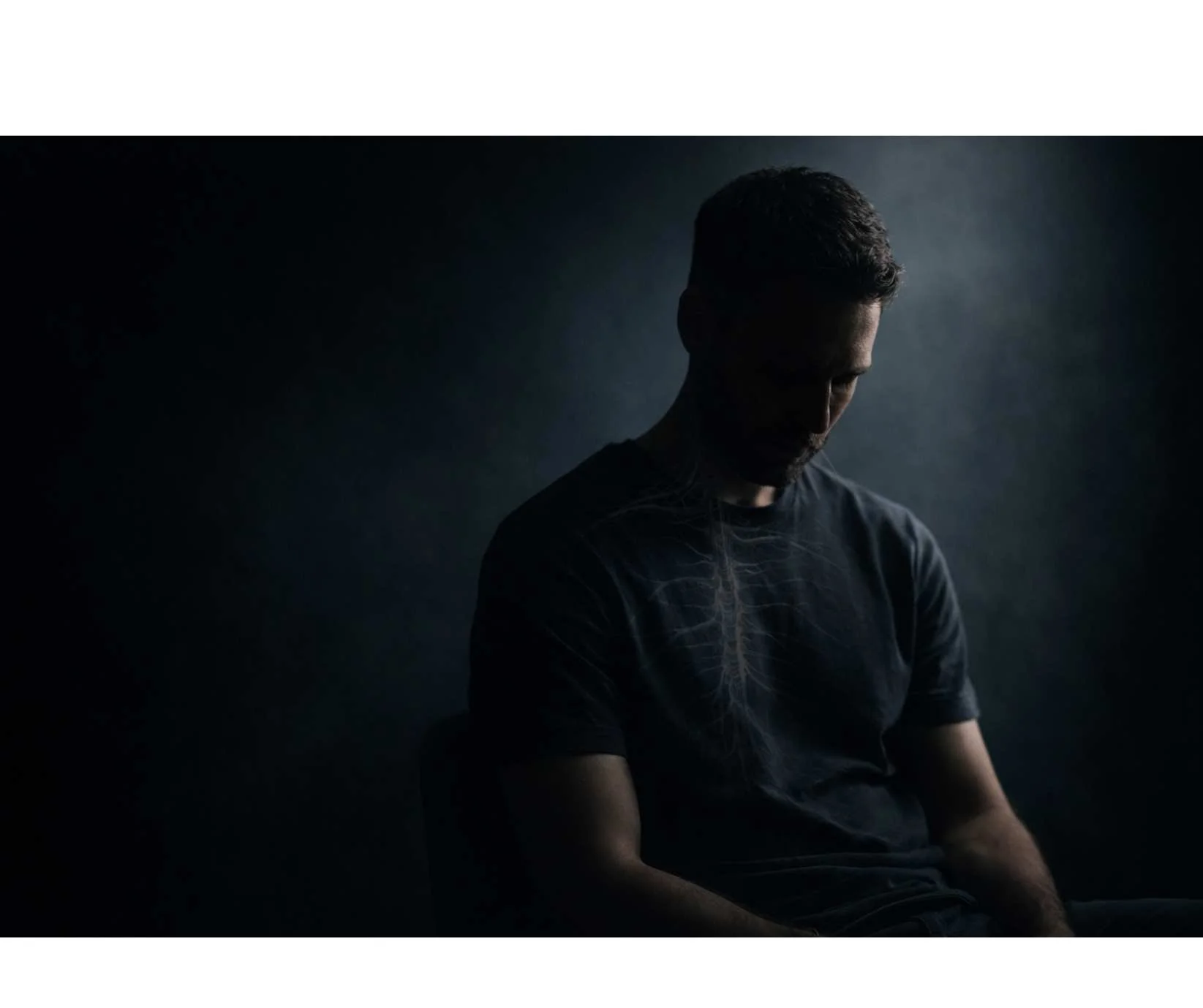

Why Depression Is Not a Personal Failure or Character Flaw

Depression is often internalized as a personal shortcoming—something to overcome with willpower, positivity, or greater effort. This interpretation is understandable, but it is inaccurate. From a physiological perspective, depressive symptoms reflect changes in how the brain and body are regulating stress, energy, and emotional processing, not a failure of character or resilience.

Mood regulation depends on coordinated signaling across multiple systems, including stress response, immune activity, metabolic stability, sleep regulation, and neural energy availability. When these systems are under sustained strain, the brain adapts in ways that prioritize conservation and protection. Reduced motivation, emotional flattening, withdrawal, and fatigue are common expressions of this adaptive shift.

In this context, depression represents a functional response to prolonged demand, not a personal deficit. Symptoms emerge when adaptive capacity is exceeded, not because effort or intention is lacking.

This framing also helps explain why people with depression often report that encouragement to “try harder” or “think positively” feels ineffective or even invalidating. These approaches assume voluntary control over processes that are largely governed by physiology. Improvement typically follows changes in biological context—such as reduced system load or improved regulatory stability—rather than increased self-discipline alone.

Understanding depression in this way can reduce self-blame and clarify why recovery is rarely linear. Fluctuations in symptoms often correspond to changes in stress exposure, health status, sleep quality, or cumulative demand, reinforcing that depression tracks with internal conditions rather than personal worth or effort.

When a Functional Medicine Evaluation May Be Appropriate

A functional medicine evaluation is most appropriate when depressive symptoms are persistent, recurrent, or context-sensitive, rather than isolated or situational. It is particularly relevant when standard approaches have provided partial relief but symptoms continue to fluctuate or return under stress.

This type of evaluation is not based on symptom severity alone. Instead, it considers whether underlying physiological patterns may be contributing to ongoing vulnerability.

Situations Where Additional Evaluation May Be Helpful

A functional medicine perspective may be useful when depression is accompanied by other signs of systemic strain, such as:

Ongoing fatigue or low stress tolerance

Sleep disruption or circadian irregularity

Cognitive fog or slowed mental processing

Digestive symptoms, food sensitivities, or inflammatory conditions

Hormonal transitions or metabolic instability

Mood symptoms that worsen with illness, stress, or poor sleep

These patterns suggest that mood regulation may be influenced by broader biological context rather than neurotransmitter signaling alone.

When Symptoms Do Not Follow a Linear Course

Depression that improves and then relapses—particularly in response to predictable stressors—often reflects limited physiological reserve rather than treatment resistance. In these cases, understanding which systems are operating near threshold can help explain why symptoms remain sensitive to change.

A functional medicine evaluation focuses on identifying where regulatory capacity is constrained and which contributors are most likely to sustain system load over time.

How This Approach Fits Alongside Existing Care

Functional medicine is not positioned as a replacement for psychiatric or primary care. Instead, it provides an additional lens for understanding contributors that may not be captured through symptom-based assessment alone.

This perspective can be especially helpful for individuals seeking a clearer explanation of why symptoms behave the way they do, even when treatment has been appropriate and carefully managed.

How Root-Cause Evaluation Differs From Symptom-Based Assessment

Conventional assessment of depression is largely symptom-driven. Diagnostic criteria and severity scales are used to identify patterns of mood, behavior, and functional impairment, which then guide treatment selection. This approach is effective for classification and risk stratification, but it provides limited insight into why depressive symptoms developed or why they behave differently across individuals.

A root-cause evaluation approaches depression from a different angle. Rather than focusing primarily on symptom clusters, it examines the physiological context in which those symptoms arise. The emphasis is on identifying patterns of system strain that influence brain regulation over time, including stress response capacity, inflammatory burden, metabolic stability, sleep regulation, and other contributors that shape mood resilience.

What Is Evaluated Beyond Symptoms

In a root-cause framework, symptoms are considered signals rather than endpoints. Evaluation looks for factors that may be sustaining depressive physiology even when symptoms fluctuate, such as chronic stress load, immune activation, circadian disruption, nutrient insufficiency, or cumulative environmental exposure.

This broader view helps explain why two individuals with similar symptom profiles may have very different underlying drivers, and why the same intervention can produce variable results depending on biological context.

Why This Perspective Changes Clinical Understanding

By shifting the focus from symptom suppression to system regulation, a root-cause evaluation provides a more precise explanation for persistence, relapse, or partial response. It clarifies whether depressive symptoms are being driven primarily by ongoing physiological demand, limited reserve capacity, or instability across interacting systems.

This does not replace conventional diagnosis or psychiatric care. Instead, it adds an additional layer of understanding that can inform how depression is interpreted over time—particularly in cases where symptoms do not follow a predictable or linear course.

Understanding depression at a root-cause level can clarify why symptoms persist, fluctuate, or respond inconsistently over time. A systems-based evaluation focuses on identifying the physiological contributors that influence mood regulation rather than relying on symptom severity alone.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Functional Medicine for Depression

Do SSRIs work for depression?

SSRIs can reduce symptoms for some individuals, particularly in moderate to severe depression. However, responses vary widely, and many people experience partial benefit, no benefit, or significant side effects, including:

Emotional blunting or feeling “flat”

Fatigue or low energy

Insomnia or disrupted sleep

Weight gain or metabolic changes

Agitation, restlessness, or increased anxiety

Decreased libido or sexual dysfunction

Digestive issues such as nausea, diarrhea, constipation, bloating, reflux, or appetite changes

From a functional medicine perspective, SSRIs are not viewed as inherently “good” or “bad.” Instead, the focus is on understanding why depressive symptoms developed in the first place and identifying the biological, lifestyle, and environmental factors that may be driving or perpetuating them — whether or not medication is part of the care plan.

Is depression really caused by a chemical imbalance?

Depression is rarely caused by a single neurotransmitter imbalance. While serotonin and other neurotransmitters are involved in mood regulation, they represent only one part of a much larger physiological picture.

Inflammation, chronic stress physiology, gut-brain signaling, nutrient availability, hormonal balance, metabolic health, sleep quality, environmental exposures, and genetics all influence brain chemistry. From a functional medicine standpoint, neurotransmitter changes are often downstream effects, not the original cause.

Why do antidepressants cause such different side effects in different people?

Antidepressants affect neurotransmitter signaling throughout the entire body, not just the brain. Serotonin receptors are found in the gut, immune system, blood vessels, and nervous system, which explains why side effects can involve digestion, sleep, energy, sexual function, and emotional processing.

Individual differences in genetics, liver metabolism, gut health, nutrient status, inflammation, and nervous system tone all influence how a person responds. This variability is why one individual may tolerate an SSRI well, while another experiences significant side effects.

If SSRIs don’t address root causes, why do they help some people?

Depression is not a single condition with a single cause. For some individuals, altered serotonin signaling plays a meaningful role in symptom expression, and SSRIs may provide relief — particularly when other systems such as sleep, inflammation, nutrition, and stress regulation are relatively stable.

For others, depression is driven primarily by factors such as chronic stress, gut dysbiosis, inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, toxin exposure, or nutrient depletion. In these cases, medications alone may not address the underlying drivers of symptoms.

What root causes does functional medicine evaluate in depression?

Functional medicine looks upstream to identify recurring contributors that disrupt mood regulation. These commonly include chronic stress and HPA-axis dysregulation, gut dysbiosis or intestinal permeability, nutrient deficiencies, inflammatory or environmental triggers, metabolic imbalance, and genetic or epigenetic vulnerability.

These factors often overlap and interact, creating biological patterns such as neuroinflammation, impaired neurotransmitter production, altered stress signaling, and reduced brain energy metabolism.

Can gut health really affect mood and depression?

Yes. The gut and brain communicate continuously through immune pathways, the vagus nerve, microbial metabolites, and neurotransmitter precursors. Disruptions in gut bacteria or intestinal barrier integrity can increase systemic inflammation and alter brain signaling.

It is common for digestive symptoms — such as bloating, constipation, diarrhea, reflux, or food sensitivities — to coexist with mood symptoms, reflecting this gut–brain connection rather than separate conditions.

Which nutrient deficiencies are most often linked to low mood?

Several nutrients are essential for healthy brain function and mood regulation. Deficiencies most commonly associated with depression include B vitamins (especially B6, B12, and folate), vitamin D, magnesium, and omega-3 fatty acids.

These nutrients support neurotransmitter synthesis, mitochondrial energy production, nervous system stability, and inflammatory balance. While deficiencies do not explain every case of depression, they are frequent and often overlooked contributors.

Should I stop my antidepressant if I want a functional medicine approach?

No. Antidepressant medications should never be stopped or adjusted without guidance from the prescribing clinician. A functional medicine approach is designed to work alongside conventional care, with a focus on identifying underlying contributors and improving overall resilience.

Any decisions about medication changes should be individualized, gradual, and medically supervised.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

National Institute of Mental Health – Major depressive disorder

Journal of Medical Internet Research – Understanding side effects of antidepressants: a large-scale longitudinal analysis

National Institute of Mental Health – Depression: clinical overview and epidemiology

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – Antidepressant use among persons aged 12 and over in the United States

The Lancet – Antidepressant drug effects and depression severity: a patient-level meta-analysis

BMJ – Initial severity and antidepressant benefits: re-analysis of FDA trial data

The British Journal of Psychiatry – Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors versus placebo in major depressive disorder

Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology – Comparative side-effect profiles of fluoxetine and other SSRIs

Autonomic Neuroscience – Sympathetic–parasympathetic balance, stress physiology, and mental health regulation

Clinical & Experimental Immunology – Psychoneuroimmunology and the intestinal microbiota

Toxicology – Neuropsychiatric effects of mycotoxin exposure

Molecular Psychiatry – Association between MTHFR polymorphisms and psychiatric disorders

American Journal of Psychiatry – Methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase function and psychiatric disease risk