Why Poor Sleep Is More Harmful Than You Think for Gut, Hormones, and Metabolic Health

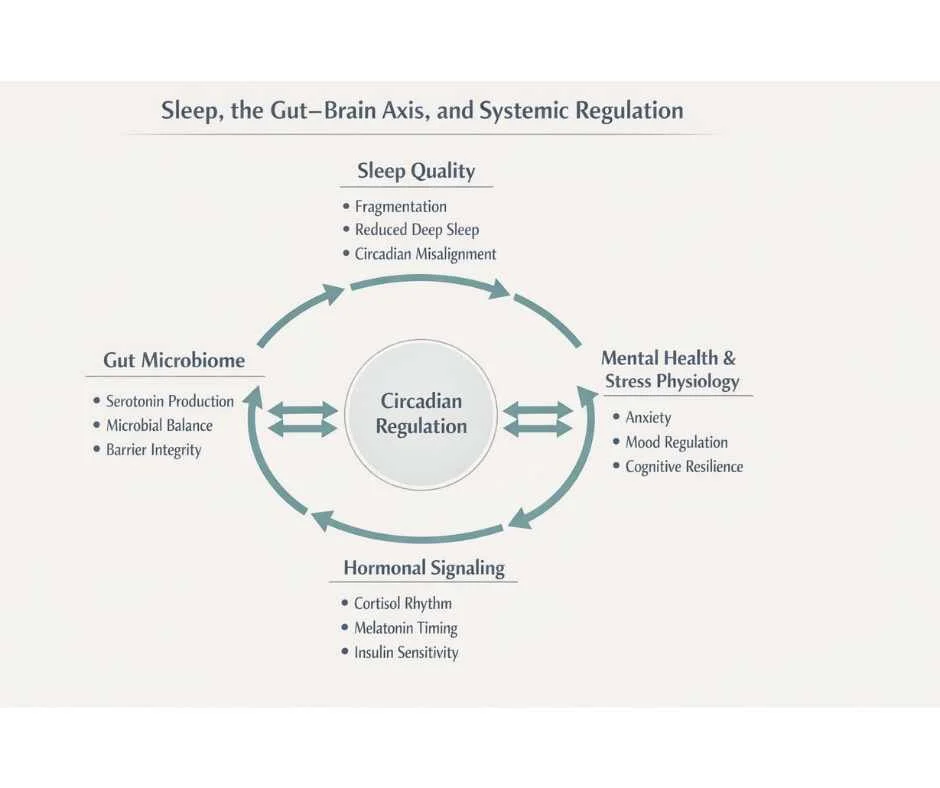

How Disrupted Sleep Alters Gut Health, Hormonal Signaling, Metabolism, and Mental Health Through Circadian Dysregulation

Sleep is not a passive state of rest—it is an active biological process that regulates nearly every system in the body. Yet in modern healthcare and daily life, sleep is often treated as optional, secondary, or easily sacrificed in favor of productivity, exercise, or diet. This assumption is not only incorrect—it is biologically costly.

Chronic poor sleep disrupts the body’s ability to regulate hormones, stabilize blood sugar, maintain gut integrity, modulate inflammation, and support cognitive and emotional resilience. Over time, these disruptions compound, increasing the risk of metabolic disease, cardiovascular events, immune dysfunction, mood disorders, and neurodegenerative decline. In many cases, sleep disturbance is not a symptom—it is a primary driver of systemic imbalance.

Sleep disorders and suboptimal sleep patterns are now widespread. Estimates suggest that up to 40% of adults experience insomnia symptoms, while an additional 20–30% report poor sleep quality that falls short of restorative needs. Importantly, damage does not require total sleep deprivation. Fragmented sleep, circadian misalignment, and insufficient deep sleep can impair physiological repair even when total sleep hours appear “normal.”

Understanding why poor sleep is so harmful requires moving beyond the idea of sleep as simple rest. During sleep, the body coordinates tissue repair, hormone synthesis, immune surveillance, toxin clearance, and neural recalibration. When sleep quality or timing is disrupted, these processes become inefficient or incomplete—shifting the body toward stress physiology rather than recovery.

This article examines how poor sleep affects the body at a systems level, including its impact on gut health, hormonal regulation, metabolic stability, and mental health—and why restoring circadian balance is foundational to long-term health.

Why Poor Sleep Is a Systems-Level Health Risk

Poor sleep is often framed as a lifestyle inconvenience, but biologically it reflects a failure of regulation across multiple interconnected systems. Sleep is the primary window during which the body shifts from environmental engagement into internal repair, recalibration, and recovery. When sleep is disrupted—by insufficient duration, fragmented architecture, or circadian misalignment—the consequences are not isolated. They cascade across the body.

Sleep Regulates Hormones, Metabolism, Immunity, and Brain Function

During healthy sleep, the brain and body coordinate multiple high-demand processes simultaneously, including:

Autonomic nervous system balancing

Hormone synthesis and signaling

Glymphatic and cellular detoxification

Immune surveillance and repair

Memory consolidation and emotional processing

These processes are interdependent. Disruption in one domain amplifies dysfunction in others, which explains why chronic sleep disturbance rarely presents as a single symptom and instead appears as clusters of seemingly unrelated issues—such as fatigue with anxiety, digestive dysfunction with mood changes, or metabolic instability alongside hormonal imbalance (1).

Why Even Mild Sleep Problems Have Serious Health Effects

Poor sleep does not need to be extreme to be biologically damaging. Research shows that chronic, subclinical disruptions—including reduced deep (NREM) sleep, frequent nighttime awakenings, and inconsistent sleep–wake timing—can impair glucose regulation, elevate inflammatory signaling, and dysregulate stress hormone rhythms over time (2). These changes often develop silently and may precede diagnosable disease by years, making sleep disturbance an early but underrecognized driver of long-term health decline.

Why Sedation Is Not the Same as Restorative Sleep

This systems-level impact explains why symptom-based approaches—such as sedatives, alcohol, or behavioral suppression—frequently fail to produce lasting improvement. These strategies may induce unconsciousness without restoring the physiological repair processes that define healthy sleep.

True sleep restoration requires addressing the upstream regulatory networks that govern circadian rhythm, stress physiology, and nervous system tone—rather than forcing sleep in a body that remains locked in a stress-adapted state.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

Sleep, the Nervous System, and Stress Physiology

Sleep and the nervous system are inseparable. Healthy sleep depends on the body’s ability to shift out of a state of vigilance and into one of safety, repair, and restoration. When this shift does not occur, the nervous system remains biased toward threat detection rather than recovery, making deep, restorative sleep physiologically difficult—even when fatigue is extreme.

Autonomic Nervous System Imbalance and Hyperarousal

Under normal conditions, sleep onset is accompanied by a transition from sympathetic (fight-or-flight) dominance to parasympathetic (rest-and-digest) activity. This shift allows heart rate, blood pressure, muscle tone, and cognitive alertness to decrease in preparation for deep sleep.

In individuals with chronic poor sleep, this transition often fails to occur. Instead, the nervous system remains in a state of hyperarousal, characterized by elevated alertness, racing thoughts, shallow sleep, and frequent nighttime awakenings. This pattern is common in people with chronic stress exposure, anxiety, trauma histories, pain syndromes, and inflammatory conditions (3).

HPA Axis Dysfunction and Cortisol Rhythm Disruption

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis plays a central role in regulating sleep–wake cycles through its control of cortisol. In a healthy circadian rhythm, cortisol levels peak in the early morning to promote alertness and gradually decline throughout the day, reaching their lowest point in the evening to allow melatonin-driven sleep initiation.

In people with insomnia or chronic sleep disruption, this rhythm is often altered. Common patterns include elevated nighttime cortisol, flattened daily cortisol curves, or delayed cortisol clearance. These abnormalities are associated with difficulty falling asleep, frequent nighttime waking, early-morning awakening, and non-restorative sleep (4).

Chronic stress further compounds this dysfunction. Repeated activation of the HPA axis reduces its adaptive flexibility, making it harder for the body to downshift into recovery mode at night. Over time, this reinforces a cycle in which poor sleep increases stress reactivity, and heightened stress further degrades sleep quality (5).

Why Nervous System Dysregulation Prevents Deep and REM Sleep

Deep NREM sleep and REM sleep require a state of neurological safety. When the nervous system perceives threat—whether psychological, inflammatory, metabolic, or environmental—it prioritizes vigilance over repair. This results in lighter sleep stages, fragmented sleep architecture, and reduced time spent in the most restorative phases of sleep.

This explains why individuals with chronic insomnia often report profound exhaustion despite spending adequate time in bed. The issue is not a lack of opportunity for sleep, but an inability of the nervous system to permit the depth of sleep required for full physiological recovery.

Circadian Rhythm Disruption and Hormonal Dysregulation

The circadian rhythm functions as the body’s master timing system, coordinating when hormones are released, tissues repair, and metabolic processes shift between energy use and recovery. Sleep disruption does not simply shorten rest—it destabilizes this timing system, leading to widespread hormonal miscommunication throughout the body.

Cortisol and Melatonin Rhythm Inversion

Two hormones sit at the core of circadian regulation: cortisol and melatonin. Under healthy conditions, these hormones follow an inverse rhythm. Cortisol rises in the morning to promote alertness and energy availability, while melatonin rises in the evening to signal darkness, safety, and sleep initiation.

When circadian rhythm is disrupted—through inconsistent sleep timing, nighttime light exposure, chronic stress, or nervous system hyperarousal—this relationship begins to invert. Cortisol may remain elevated late into the evening, while melatonin release becomes delayed, blunted, or fragmented. This pattern makes it difficult to fall asleep, stay asleep, or reach deeper sleep stages even when exhaustion is present (6).

How Poor Sleep Disrupts Insulin, Thyroid, and Sex Hormone Signaling

Circadian disruption does not affect cortisol and melatonin in isolation. Because these hormones act as timing cues for other endocrine systems, their dysregulation can impair broader hormonal signaling, including:

Impaired insulin sensitivity and glucose regulation

Altered thyroid hormone signaling and metabolic rate

Disrupted sex hormone balance, particularly estrogen and progesterone rhythms

These changes help explain why chronic sleep disturbance is frequently associated with weight gain, blood sugar instability, temperature dysregulation, and fatigue that does not resolve with rest alone (7).

Sleep Disruption Across the Female Hormonal Lifespan

Hormonal transitions amplify circadian vulnerability. Many women experience worsening sleep during phases of hormonal fluctuation, including the premenstrual phase, perimenopause, and menopause. Declining or fluctuating estrogen and progesterone levels alter thermoregulation, neurotransmitter balance, and nervous system tone—factors that directly affect sleep continuity and depth (8).

From a Traditional Chinese Medicine perspective, these patterns often reflect deficiencies in yin, blood, or kidney essence, or the presence of heat that disrupts the mind’s ability to settle at night. Although the explanatory frameworks differ, both models recognize that hormonal imbalance and sleep disturbance reinforce one another in a bidirectional loop.

→ Hormone & Metabolic Optimization

Poor Sleep and Gut–Brain Axis Dysregulation

Sleep and gut health are tightly interconnected through bidirectional signaling between the nervous system, immune system, and microbiome. Disruption of sleep alters this communication network, contributing to changes in neurotransmitter production, inflammatory tone, and intestinal barrier integrity. Over time, these shifts can amplify both sleep disturbance and systemic symptoms.

Gut Microbiome and Neurotransmitter Production

Although neurotransmitters are often associated with the brain, a significant portion are produced in the gastrointestinal tract. The gut microbiome plays a central role in synthesizing and modulating compounds such as serotonin, dopamine, and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), all of which influence mood, stress tolerance, and sleep regulation.

Approximately 90 percent of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gut. Serotonin serves as a direct precursor to melatonin, meaning impaired gut function can reduce the body’s ability to initiate and sustain healthy sleep. When microbial balance is disrupted—by stress, inflammation, poor diet, or circadian misalignment—this pathway becomes compromised, making melatonin production less efficient even when sleep opportunity is adequate (9).

Sleep Loss, Inflammation, and Intestinal Barrier Integrity

Poor sleep also increases inflammatory signaling throughout the body, including within the gastrointestinal tract. Elevated inflammatory mediators can weaken tight junctions in the intestinal lining, increasing permeability and immune activation. This process further disrupts microbiome balance and reinforces stress signaling back to the brain, perpetuating a cycle of sleep disturbance and gut dysfunction (10).

Over time, this feedback loop may manifest as bloating, food sensitivities, irregular digestion, mood changes, or fatigue that worsens despite adequate time in bed.

The Gut–Brain–Sleep Feedback Loop

At this stage of dysregulation, sleep disturbance is no longer an isolated issue. Instead, it becomes part of a self-reinforcing loop in which poor sleep impairs gut signaling, altered gut signaling increases neuroinflammation and stress physiology, and heightened stress further degrades sleep quality.

This framework helps explain why addressing sleep in isolation often produces limited results, and why lasting improvement frequently requires restoring balance across the gut–brain axis rather than targeting symptoms alone.

→ Gut Health & Digestive Restoration

Metabolic and Inflammatory Consequences of Chronic Sleep Loss

Sleep plays a central role in metabolic regulation and immune balance. When sleep is consistently disrupted, the body shifts toward a state of energy conservation, stress adaptation, and low-grade inflammation. Over time, these changes increase vulnerability to metabolic dysfunction and chronic disease—even in individuals who maintain a healthy diet and exercise routine.

Sleep Loss, Insulin Resistance, and Glucose Dysregulation

Adequate sleep is essential for maintaining insulin sensitivity and stable blood sugar control. Chronic sleep restriction and fragmented sleep have been shown to impair glucose tolerance, increase insulin resistance, and alter appetite-regulating hormones. These effects can occur independently of caloric intake or physical activity levels, underscoring sleep’s role as a metabolic regulator rather than a passive recovery period (11).

As insulin sensitivity declines, the body becomes less efficient at managing post-meal glucose, signaling the pancreas to produce more insulin. Over time, this contributes to metabolic strain, energy crashes, and increased fat storage—particularly when circadian rhythm disruption is present.

How Poor Sleep Drives Chronic Inflammation

Sleep is a critical modulator of immune signaling. During deep sleep, the body downshifts inflammatory activity and prioritizes tissue repair. When sleep is shortened or fragmented, inflammatory mediators remain elevated, leading to a persistent low-grade inflammatory state.

This inflammatory burden contributes to endothelial dysfunction, impaired immune surveillance, and increased pain sensitivity. It also reinforces nervous system hyperarousal, making it more difficult to achieve restorative sleep in subsequent nights and perpetuating a self-reinforcing cycle of stress and inflammation (12).

Why Sleep Disruption Impairs Weight Regulation and Energy Balance

Poor sleep alters the balance of hormones involved in hunger and satiety, including leptin and ghrelin. Reduced sleep duration has been associated with increased appetite, heightened cravings for calorie-dense foods, and reduced energy expenditure. Importantly, these effects are not purely behavioral; they reflect physiological adaptations to perceived energy stress (13).

This helps explain why individuals with chronic sleep disturbance may struggle with weight regulation despite consistent lifestyle efforts. Without restoring sleep quality and circadian alignment, metabolic interventions alone often yield limited or temporary results.

Mental Health, Cognitive Function, and Emotional Regulation

Sleep is essential for cognitive processing, emotional stability, and psychological resilience. During healthy sleep, the brain consolidates memories, processes emotional experiences, and recalibrates stress responses. When sleep quality or timing is disrupted, these regulatory processes become impaired, increasing vulnerability to mood disturbances and cognitive dysfunction.

REM Sleep, Emotional Processing, and Mood Stability

REM sleep plays a critical role in emotional regulation by helping the brain integrate emotionally charged experiences while reducing their physiological intensity. Disrupted or shortened REM sleep has been associated with increased emotional reactivity, irritability, and difficulty modulating stress responses. Over time, this can contribute to symptoms of anxiety and depression, particularly in individuals already exposed to chronic stress or inflammation (14).

Importantly, poor sleep does not directly cause mental health disorders in a linear way. Instead, it lowers the threshold at which emotional stressors become overwhelming, reducing psychological flexibility and resilience.

Sleep, Cognitive Function, and Memory Consolidation

Sleep is also necessary for learning, memory consolidation, and executive function. Both deep NREM sleep and REM sleep contribute to different aspects of cognitive processing, including attention, working memory, and decision-making.

Chronic sleep disruption has been linked to impaired concentration, slower reaction times, reduced problem-solving capacity, and increased error rates. These effects are often subtle at first but accumulate over time, affecting work performance, academic functioning, and daily decision-making (15).

Sleep Loss and Stress Reactivity in the Brain

When sleep is inadequate, the brain’s stress-response systems become more reactive. The amygdala shows heightened responsiveness to negative stimuli, while prefrontal regulatory control weakens. This neurobiological shift favors threat detection over rational processing, contributing to heightened anxiety, emotional volatility, and reduced coping capacity (16).

This pattern helps explain why individuals with chronic sleep disturbance often report feeling emotionally “on edge,” overwhelmed by minor stressors, or unable to recover from emotionally taxing experiences.

Why Sleep Quality Matters More Than Sleep Duration

Sleep is often reduced to a numbers game, with emphasis placed on achieving seven to eight hours per night. While sleep duration is important, it is only one component of restorative sleep. Sleep quality—defined by depth, continuity, timing, and architecture—ultimately determines whether the body can complete the physiological processes required for repair and regulation.

Sleep Architecture, NREM Sleep, and REM Sleep Restoration

Healthy sleep cycles between non–rapid eye movement (NREM) sleep and rapid eye movement (REM) sleep multiple times throughout the night. Deep NREM sleep supports physical repair, immune regulation, and metabolic balance, while REM sleep is essential for cognitive processing and emotional integration.

When sleep is fragmented, delayed, or misaligned with circadian rhythm, these cycles become disrupted. Individuals may spend adequate time in bed yet fail to achieve sufficient deep or REM sleep, resulting in persistent fatigue, impaired concentration, and poor stress tolerance despite seemingly “normal” sleep duration (17).

Sleep Fragmentation, Micro-Arousals, and Non-Restorative Sleep

Sleep quality is particularly vulnerable to micro-arousals—brief, often unrecognized awakenings that interrupt sleep architecture. These disruptions may be caused by stress physiology, environmental factors, pain, inflammation, or breathing irregularities. Even when the sleeper does not consciously awaken, repeated micro-arousals prevent the brain from sustaining deeper sleep stages.

Over time, fragmented sleep reduces the body’s ability to complete restorative processes, increasing inflammatory signaling and nervous system reactivity. This explains why individuals with poor sleep quality often feel unrefreshed upon waking, regardless of total sleep time (18).

Circadian Timing, Sleep Efficiency, and Biological Alignment

The timing of sleep relative to the circadian clock also plays a critical role in sleep quality. Sleeping at biologically misaligned times—such as late-night bedtimes or rotating schedules—reduces sleep efficiency and alters hormone release patterns. In these cases, even extended sleep duration may fail to provide full restorative benefit.

This reinforces the principle that improving sleep requires attention not only to how long one sleeps, but to when and how sleep occurs within the body’s internal timing system.

Restoring Sleep Requires Regulation, Not Sedation

When sleep becomes difficult, many individuals turn to substances or interventions that suppress wakefulness rather than restore physiological balance. While these approaches may induce unconsciousness, they do not necessarily support the neurological, hormonal, and metabolic processes that define restorative sleep.

Why Sedatives and Alcohol Do Not Restore Healthy Sleep

Alcohol and many sleep medications act as central nervous system depressants. Although they can shorten sleep onset, they alter sleep architecture by reducing time spent in deep NREM sleep and REM sleep. This interference limits tissue repair, immune regulation, and emotional processing—often resulting in fragmented sleep and early-morning awakening (19).

Over time, reliance on sedative strategies can worsen sleep quality by increasing tolerance, rebound wakefulness, and circadian disruption. Rather than resolving the underlying issue, these approaches may reinforce the very dysregulation they are intended to address.

Sleep as a Regulatory Outcome of Nervous System Balance

Healthy sleep emerges when the body perceives safety, timing, and internal balance. This requires coordinated regulation across the nervous system, endocrine signaling, metabolic function, and inflammatory tone. When these systems are overstimulated or misaligned, the brain prioritizes vigilance over recovery, making deep sleep inaccessible regardless of fatigue level.

From this perspective, sleep difficulty is not a failure of willpower or discipline. It is a physiological signal that regulatory systems remain in a state of activation rather than repair.

Addressing the Root Causes of Sleep Disruption

Restoring sleep quality therefore requires identifying and correcting the upstream drivers that interfere with regulation. These may include chronic stress physiology, circadian rhythm disruption, inflammatory burden, metabolic instability, or gut–brain signaling imbalance. When these contributors are addressed, sleep often improves as a downstream effect rather than a forced outcome.

This regulatory approach explains why comprehensive sleep restoration strategies focus on system-wide balance rather than symptom suppression alone.

How to Support Healthy Sleep Regulation at Home

Once the systems that govern sleep are understood, certain foundational behaviors can help reinforce circadian signaling and reduce nighttime physiological stress. These steps do not replace clinical evaluation, but they can support the body’s ability to transition into restorative sleep.

Establish a Consistent Sleep–Wake Schedule

Going to bed and waking at the same time each day helps anchor the circadian clock and improves the timing of cortisol and melatonin release. Irregular schedules—even with adequate sleep duration—can impair sleep quality.

Reduce Evening Neurological Stimulation

Late-night work, emotionally charged conversations, and stimulating media activate stress physiology. Replacing these activities with calming routines—such as reading, gentle stretching, journaling, or quiet reflection—helps signal safety to the nervous system.

Optimize Light Exposure for Circadian Rhythm Support

Darkness is a biological signal for sleep. A fully dark sleeping environment supports melatonin release and sleep depth. In the evening, reducing overhead lighting and screen exposure can further reinforce circadian cues. When screens are unavoidable, blue-light–blocking strategies may reduce disruption.

Be Mindful of Caffeine and Alcohol Intake

Caffeine can impair sleep quality long after its stimulating effects are felt, even when sleep onset appears unaffected. Alcohol, while sedating, disrupts REM sleep and increases nighttime awakenings, leading to non-restorative sleep.

Why Sleep Medications May Worsen Sleep Quality Over Time

Many sleep medications suppress wakefulness without restoring healthy sleep architecture. Long-term reliance may worsen fragmentation and circadian disruption rather than resolve underlying drivers.

Allow Adequate Time Between Eating and Sleep

Late meals increase metabolic demand when the body should be prioritizing repair. Allowing adequate time between eating and sleep supports digestive ease and overnight recovery.

Support the Nervous System and Gut–Brain Axis

Approaches that reduce pain, anxiety, and inflammatory burden—such as acupuncture or targeted microbiome support—may indirectly improve sleep quality by addressing contributors rather than symptoms (11–13).

→ Acupuncture & Nervous System Regulation

Use Sleep Tracking Tools for Awareness, Not Control

Sleep-monitoring apps can help identify patterns in sleep duration and fragmentation, but they should be used as observational tools rather than performance metrics.

When Poor Sleep Signals an Underlying Health Issue

Occasional sleep disruption is common and often resolves with short-term changes in routine or environment. However, when poor sleep becomes persistent, it may reflect underlying physiological imbalance rather than a transient lifestyle issue. In these cases, sleep disturbance functions as an early warning signal rather than an isolated complaint.

Sleep Patterns That Suggest Deeper Physiologic Dysregulation

Sleep issues warrant closer evaluation when they are accompanied by patterns such as:

Difficulty falling or staying asleep most nights

Early-morning waking with inability to return to sleep

Persistent fatigue despite adequate time in bed

Heightened anxiety, mood changes, or cognitive fog

Digestive symptoms, blood sugar instability, or hormonal fluctuations

These combinations suggest that sleep disruption may be embedded within broader nervous system, hormonal, metabolic, or inflammatory dysregulation.

Why Persistent Sleep Problems Require Clinical Evaluation

When sleep disturbance is driven by upstream imbalances, symptom-based approaches alone are unlikely to produce lasting improvement. Without identifying contributing factors—such as circadian rhythm disruption, stress physiology, gut–brain signaling dysfunction, or metabolic instability—interventions may temporarily suppress symptoms while underlying drivers persist.

Early evaluation allows these patterns to be addressed before they consolidate into more entrenched chronic conditions. In many cases, improving sleep quality becomes an indicator of broader system restoration rather than the sole objective of care.

Sleep as a Foundation of Long-Term Health, Not a Lifestyle Hack

Sleep is not a passive state or a productivity tool—it is a foundational biological process that governs regulation across the nervous system, hormones, metabolism, immune function, and mental health. When sleep is disrupted, these systems do not fail independently; they destabilize together, often long before clear disease labels emerge.

Persistent sleep disturbance is rarely about willpower, discipline, or a lack of effort. More often, it reflects underlying dysregulation that prevents the body from shifting out of vigilance and into repair. In this context, improving sleep is not about forcing rest, but about restoring the conditions that allow sleep to occur naturally and deeply.

When sleep quality improves, it often serves as an early indicator that broader physiological balance is being restored. For this reason, sleep deserves attention not as an isolated symptom, but as a central pillar of long-term health, resilience, and recovery.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Poor Sleep

Why is poor sleep so damaging to overall health?

Poor sleep disrupts regulation across multiple systems at once, including the nervous system, hormones, metabolism, immune function, and brain health. Unlike short-term sleep loss, chronic poor sleep prevents the body from completing essential repair and recovery processes, allowing stress physiology and inflammation to dominate over time.

Can you still be unhealthy if you sleep enough hours but wake up tired?

Yes. Sleep quality matters as much as sleep duration. Fragmented sleep, reduced deep sleep, frequent micro-awakenings, or circadian misalignment can prevent restorative processes from occurring even when total sleep time appears adequate. This often results in persistent fatigue, brain fog, and poor stress tolerance.

How does poor sleep affect hormones?

Poor sleep disrupts circadian timing, which alters the normal release patterns of hormones such as cortisol, melatonin, insulin, estrogen, and progesterone. Over time, this dysregulation can contribute to blood sugar instability, weight changes, temperature sensitivity, mood shifts, and worsening sleep quality.

Is poor sleep linked to gut problems?

Yes. Sleep and gut health are connected through the gut–brain axis. Poor sleep can alter the gut microbiome, increase inflammation, and impair serotonin production, which is required for melatonin synthesis. In turn, gut dysfunction can further disrupt sleep, creating a self-reinforcing cycle.

Why does stress make it so hard to sleep even when you’re exhausted?

Stress keeps the nervous system in a state of vigilance. When the body perceives threat—whether emotional, inflammatory, or metabolic—it prioritizes alertness over repair. This makes it difficult to access deep and REM sleep, even when physical exhaustion is present.

Does alcohol really make sleep worse?

Yes. While alcohol may make it easier to fall asleep, it disrupts normal sleep architecture by suppressing REM sleep and increasing nighttime awakenings. This leads to non-restorative sleep and worsened fatigue, often without the person realizing why they feel unrefreshed.

When should sleep problems be evaluated clinically?

Sleep issues should be evaluated when they persist for weeks to months, interfere with daily functioning, or occur alongside symptoms such as anxiety, depression, digestive problems, hormonal changes, chronic pain, or metabolic instability. In these cases, sleep disturbance is often a signal of deeper physiological imbalance.

Can improving sleep help other health issues?

Often, yes. Because sleep regulates so many systems, improvements in sleep quality are frequently accompanied by better mood stability, improved digestion, enhanced energy, and greater metabolic resilience. In many cases, sleep improvement reflects broader system regulation rather than an isolated change.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Sleep Medicine Reviews – Insomnia: prevalence, consequences, and evidence-based treatment approaches

Institute for Functional Medicine – Good sleep hygiene and its role in immune resilience

The Lancet – The cumulative effects of sleep loss on metabolic, cardiovascular, and neurologic health

National Institute of Child Health and Human Development – Inadequate sleep and health consequences

Nature Reviews Immunology – Sleep deprivation and inflammatory signaling pathways

Journal of Personalized Medicine – A functional medicine approach to insomnia

Psychoneuroendocrinology – The HPA axis, stress physiology, and sleep disturbance

Institute for Functional Medicine – Sleep dysfunction and the role of relaxation and nervous system regulation

American Family Physician – Pharmacologic treatment of insomnia disorder

Journal of Translational Medicine – The microbiome–gut–brain axis and sleep regulation

Journal of Neuroinflammation – Sleep deprivation, neuroinflammation, and cognitive dysfunction

Journal of Neuroendocrinology – Circadian rhythm disruption and hormonal dysregulation

Frontiers in Psychiatry – Impact of sleep disturbance on stress reactivity and emotional regulation