What Is ADHD? A Brain and Nervous System Regulation Disorder — Not a Lack of Attention

How sleep, stress hormones, brain energy, and metabolism shape focus, motivation, and executive function in ADHD

If you live with ADHD, you’ve likely heard some version of this:

“You just need to focus.”

“Try harder.”

“Be more disciplined.”

Over time, those statements stop feeling like advice and start feeling like identity. They shape how you interpret your intelligence, your reliability, and even your self-worth.

But ADHD rarely feels like a lack of ability. It feels like unpredictability.

Clear-headed one day. Foggy the next.

Motivated in the morning. Mentally drained by afternoon.

Capable of intense hyperfocus on something meaningful — yet unable to begin something routine (1).

That pattern is confusing because the common explanation of ADHD is incomplete.

ADHD is not simply a deficit of attention. It is a disorder of regulation — specifically executive regulation within a highly dynamic brain–body system (2).

Executive function depends on stable sleep, balanced stress signaling, consistent metabolic energy, and integrated nervous system tone. When those foundations are stable, attention becomes more reliable. When they are unstable, focus fluctuates — sometimes dramatically.

ADHD involves more than alterations in dopamine and norepinephrine signaling pathways. Nervous system signaling, cortisol rhythms, circadian timing, mitochondrial energy production, inflammatory tone, and environmental load all influence how effectively the brain can sustain goal-directed behavior (3).

In other words, attention does not operate in isolation. It operates within context.

When regulatory systems are overloaded, performance becomes inconsistent — even in individuals who are intelligent, motivated, and capable.

Viewing ADHD through a regulation-based lens reframes the diagnosis. It moves the conversation away from character flaws and toward systems biology. It explains why symptom-only approaches often plateau — and why long-term stability requires looking at physiology, not just behavior (4).

In this article, we’ll examine:

What ADHD is beyond DSM behavioral labels

How executive dysfunction differs from lack of intelligence or motivation

Why ADHD symptoms fluctuate based on sleep, stress, inflammation, and metabolic stability

The role of brain energy and nervous system tone

Why ADHD often presents differently in adults and women

Why dopamine alone does not fully explain ADHD

What a systems-based evaluation considers when symptoms persist

What Is ADHD, Really? Beyond DSM Criteria and Behavioral Labels

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) defines ADHD by observable behaviors: inattention, impulsivity, and hyperactivity (5). That framework serves an important purpose. It standardizes diagnosis. It improves access to care. It allows clinicians to communicate within a shared system.

But it describes patterns — it does not explain mechanisms.

It tells us what ADHD looks like.

It does not explain why the brain behaves that way.

It doesn’t explain why someone can maintain intense concentration in one context and lose it completely in another.

It doesn’t explain why symptoms worsen during sleep deprivation, hormonal shifts, illness, or chronic stress.

And it doesn’t explain why ADHD may look dramatically different in childhood versus adulthood.

At a functional level, ADHD is best understood as a disorder of executive regulation — not intelligence, not motivation, and not effort.

Executive regulation refers to the brain’s ability to initiate, sustain, shift, and inhibit behavior in response to changing internal and external demands. It is dynamic. It requires coordination between prefrontal networks, reward systems, autonomic signaling, and metabolic energy delivery.

When those systems are synchronized, attention feels stable.

When they are fragmented, performance becomes unpredictable.

That distinction changes everything.

Because when ADHD is framed as a behavior problem, the solution becomes pressure and discipline.

When ADHD is understood as a regulation problem, the solution becomes system stability.

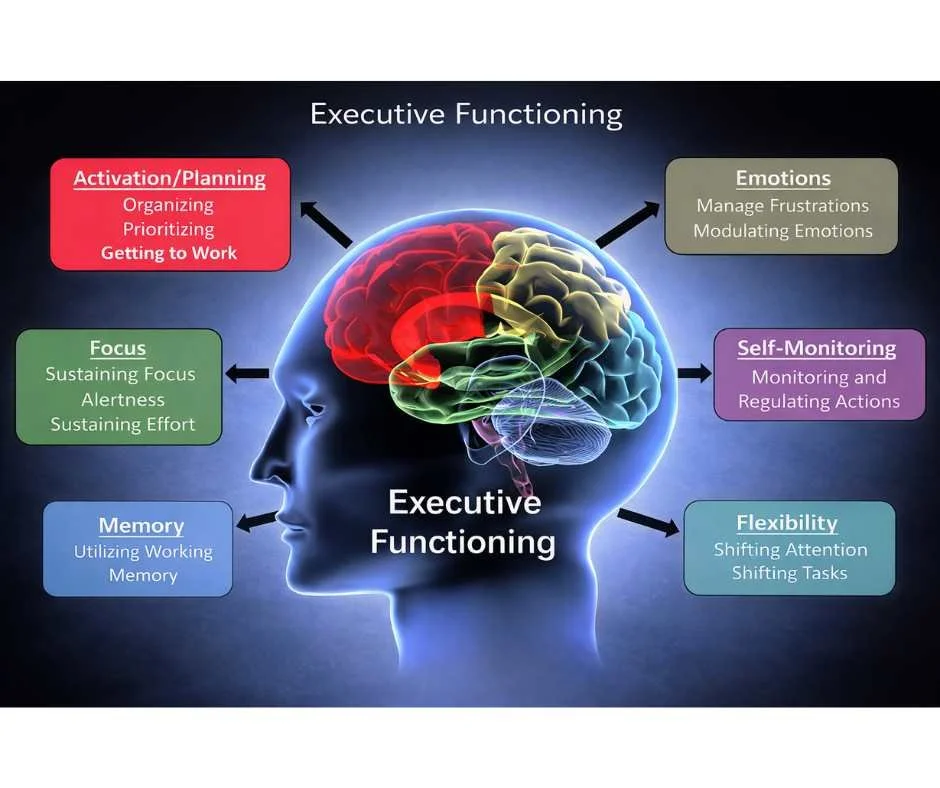

ADHD and Executive Dysfunction: It’s About Regulation, Not Intelligence

Executive functions are the brain’s management systems. They coordinate:

Task initiation

Sustained attention

Working memory

Impulse control

Emotional regulation

Cognitive flexibility

These capacities depend heavily on prefrontal cortical integration and balanced neurotransmitter signaling — particularly dopamine and norepinephrine pathways that support effort allocation and attentional filtering.

In ADHD, these abilities are not absent. They are inconsistent.

That inconsistency reflects fluctuating regulatory capacity.

For example, under conditions of urgency or novelty, dopamine signaling increases, reward circuits activate, and executive networks synchronize. Performance may become sharp and sustained.

But in low-stimulation or delayed-reward conditions, executive regulation requires more metabolic energy and stronger top-down control. If sleep has been poor, stress load is high, or blood glucose is unstable, that control weakens.

The result is not inability.

It is variability.

That’s why someone with ADHD can produce exceptional work under deadline pressure — and then struggle to initiate a routine task the next day.

It’s not a capacity issue.

It’s a regulation issue (6).

And regulation is state-dependent.

ADHD Brain Differences: Prefrontal Cortex, Reward Networks, and Inhibitory Control

Neuroimaging research links ADHD to altered activity in networks responsible for attention regulation, inhibitory control, and reward processing — particularly within the prefrontal cortex and its connections to subcortical structures such as the basal ganglia and striatal reward circuits (7).

The prefrontal cortex is the brain’s executive control center. It integrates information, suppresses distractions, prioritizes goals, and coordinates long-term planning. For these systems to function smoothly, they depend on precise timing of dopamine and norepinephrine signaling, efficient communication between cortical and subcortical regions, and stable metabolic support.

In ADHD, research suggests differences in network connectivity, signal timing, and neurotransmitter modulation — not structural damage.

The architecture is intact.

The wiring is present.

But the signaling can be less efficient and more sensitive to physiological stress.

Small shifts in sleep, stress hormones, blood glucose, or inflammatory load may disproportionately affect prefrontal function. When that happens, inhibitory control weakens, distractibility increases, and sustained effort becomes harder to maintain.

This does not reflect lower intelligence.

It reflects a system that is more vulnerable to load.

The brain works — but it works best under very specific internal conditions.

Why People With ADHD Can Hyperfocus — But Struggle With Consistency

Hyperfocus is often misunderstood as a contradiction to ADHD. In reality, it is one of the clearest demonstrations that ADHD is not a true deficit of attention.

Many individuals with ADHD can concentrate intensely when a task is:

Novel

Urgent

Time-sensitive

Personally meaningful

Under these conditions, reward networks activate strongly. Dopamine signaling increases. Prefrontal circuits synchronize. Attention becomes deep, sustained, and immersive.

In these moments, the brain is not deficient — it is optimized.

The difficulty arises when stimulation drops.

Routine, repetitive, or delayed-reward tasks require sustained top-down regulation without strong reward signaling to drive them. That type of regulation is metabolically demanding. It depends on stable energy availability, intact inhibitory control, and consistent neurotransmitter modulation (8).

When those systems are even slightly strained — from poor sleep, elevated stress, low stimulation, or cognitive fatigue — sustaining attention becomes harder.

So hyperfocus and distractibility are not opposites.

They are different regulatory states within the same nervous system.

When reward signaling is strong, focus locks in.

When it weakens, executive effort must compensate.

And that compensation is where inconsistency shows up.

Why ADHD Symptoms Fluctuate Day to Day: Sleep, Stress, and Blood Sugar

From a systems perspective, ADHD is context-sensitive.

That means symptoms are not fixed traits. They are expressions of regulatory capacity in a given moment.

Cognitive performance shifts based on:

Sleep quality

Stress exposure

Metabolic stability

Emotional load

Environmental input

These variables directly influence prefrontal cortical function — the brain region responsible for planning, inhibition, sustained attention, and impulse control.

When sleep is adequate, stress signaling is balanced, and energy delivery is stable, executive networks synchronize more efficiently. Attention feels steadier. Tasks feel more manageable.

When those systems are strained, symptoms intensify — even if motivation remains high (9).

This is why “trying harder” often fails. Regulation is not powered by willpower alone. It depends on whether the nervous system has the metabolic and hormonal stability required to sustain executive control (10).

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

ADHD and the Nervous System: Stress, Brain Energy, and Regulation

ADHD is often framed as a purely neurological or psychiatric condition. But cognitive regulation does not occur in isolation from the body.

The prefrontal cortex depends on continuous metabolic support. It is exquisitely sensitive to fluctuations in cortisol, blood glucose, inflammatory signaling, and autonomic tone. Even small disruptions in these systems can reduce inhibitory control and increase distractibility (11).

From a systems perspective, ADHD reflects strain across multiple brain–body regulatory pathways — not simply a dopamine imbalance.

Executive function is not just chemical. It is energetic.

ADHD and Brain Energy: Why Mental Fatigue and Task Avoidance Happen

The brain consumes a disproportionate share of the body’s glucose and oxygen. Sustained focus, impulse control, and emotional regulation require:

Consistent glucose availability

Efficient mitochondrial ATP production

Stable autonomic nervous system signaling

When blood sugar fluctuates — whether from irregular meals, high-glycemic foods, or prolonged stress — prefrontal efficiency declines. That decline may feel like procrastination or “lack of motivation.”

But in many cases, it reflects reduced cognitive endurance (12).

Mental fatigue in ADHD is often misunderstood. It is not laziness. It is the experience of a high-demand system operating under unstable energy conditions.

When energy delivery is inconsistent, executive function becomes inconsistent.

How Chronic Stress Worsens ADHD Symptoms

Stress signaling has direct neurobiological consequences.

Chronic activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis alters cortisol rhythms, reduces prefrontal cortical activation, and increases amygdala reactivity. In practical terms, this shifts the brain toward short-term survival prioritization and away from long-term planning and inhibition (13).

Under sustained stress:

Impulse control weakens

Emotional reactivity increases

Task persistence declines

This is why ADHD symptoms often intensify during burnout, prolonged stress, or emotional overload.

Not because discipline disappeared.

Because regulatory resources are being diverted.

ADHD and Sleep Problems: How Circadian Rhythm Affects Focus

Sleep is foundational to executive regulation.

Adequate sleep supports:

Dopamine and norepinephrine balance

Synaptic plasticity and learning consolidation

Emotional regulation

Attention stability

Delayed sleep phase and circadian misalignment are disproportionately common in ADHD. When circadian rhythm shifts later, morning executive function often suffers. Even modest chronic sleep restriction significantly amplifies inattention, irritability, and cognitive fatigue (14).

For many adults, sleep disruption is not secondary. It is central to symptom variability.

Sleep loss reduces prefrontal efficiency faster than it reduces IQ. The result is executive instability.

Can Inflammation Make ADHD Worse? What Research Suggests

Inflammatory signaling influences neurotransmission and synaptic plasticity.

Low-grade neuroinflammation has been associated with altered dopamine metabolism, reduced executive efficiency, and increased cognitive variability. Environmental toxins, chronic infections, metabolic stress, and immune activation can elevate inflammatory tone (15).

Inflammation does not create ADHD in isolation.

But it can amplify symptom expression by increasing neural noise and reducing signal clarity.

When inflammatory load rises, executive regulation often becomes more fragile.

Why ADHD Gets Worse During Burnout, Illness, and High Stress

Taken together, these mechanisms explain why ADHD symptoms are rarely static.

Executive function reflects the brain’s real-time regulatory capacity. That capacity depends on synchronized input from:

Metabolic energy systems

Stress-hormone signaling

Circadian rhythm stability

Inflammatory tone

Autonomic balance

When these systems are supported, regulation improves.

When they are strained — by stress, sleep disruption, illness, hormonal shifts, or environmental overload — regulation falters.

This variability reflects biological context, not effort or character.

ADHD does not “get worse” randomly.

It becomes more visible when regulatory demand exceeds recovery capacity.

Why ADHD Often Looks Different in Adults

ADHD does not suddenly emerge in adulthood. What changes is demand.

As life becomes more complex, regulatory requirements increase. Executive function must manage long-term planning, financial responsibility, multitasking, emotional labor, and self-directed structure. When those demands exceed available regulatory capacity, symptoms become more visible (15).

In childhood, external systems often compensate for internal instability. In adulthood, that compensation disappears.

What changes is not intelligence.

What changes is load.

This shift explains why many adults feel their ADHD has “worsened,” even if symptoms were present earlier in life. The nervous system is now operating under higher and more sustained pressure.

Why Adult ADHD Feels Worse: Loss of Structure and Executive Load

Childhood environments typically provide scaffolding:

Scheduled classes

Clear deadlines

Parental oversight

Structured expectations

These systems externally regulate time, task initiation, and prioritization.

Adulthood requires internalizing those functions. Individuals must generate structure rather than respond to it.

That transition significantly increases executive load (16).

Self-directed regulation is metabolically expensive. It depends on sustained prefrontal activation, stable dopamine signaling, and consistent energy delivery. Without external structure, small fluctuations in sleep, stress, or motivation can have amplified consequences.

The brain is doing more invisible work.

Adult ADHD and Burnout: The Hidden Role of Chronic Stress

Adult life introduces cumulative stressors that persist rather than resolve:

Career pressure and financial responsibility

Caregiving and relational complexity

Continuous digital input and task-switching

Reduced recovery time

Chronic stress alters hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis signaling, disrupts cortisol rhythms, and reduces prefrontal cortical efficiency. Over time, this shifts the brain toward reactive processing and away from sustained executive control (17).

Planning weakens. Emotional reactivity increases. Task persistence declines.

Burnout and ADHD frequently overlap because both involve depletion of regulatory capacity.

The symptoms may look like “worsening ADHD,” but often they reflect prolonged nervous system overload.

Adult ADHD and Sleep: Delayed Sleep Phase, Insomnia, and Non-Restorative Sleep

Sleep disturbances are disproportionately common in adults with ADHD.

Circadian rhythm misalignment — particularly delayed sleep phase — can shift peak cognitive function later into the day. When work schedules demand early performance, chronic sleep restriction follows.

Sleep supports:

Dopamine receptor sensitivity

Emotional processing

Prefrontal cortical recovery

Working memory consolidation

Even mild chronic sleep debt significantly amplifies inattention, irritability, and cognitive fatigue (18).

Sleep disruption does not just make someone tired.

It destabilizes executive regulation.

For many adults, restoring sleep integrity produces more noticeable improvements than increasing effort.

ADHD in Women: Hormones, Estrogen, and Late Diagnosis

Hormonal modulation adds another layer of complexity, particularly in women.

Estrogen influences dopamine signaling and prefrontal activation. Progesterone modulates GABAergic tone and stress sensitivity. Across the menstrual cycle, postpartum period, and perimenopause, these fluctuations can alter executive stability.

When estrogen declines — such as in the late luteal phase or perimenopause — dopamine signaling efficiency may decrease, making attentional control more fragile.

This helps explain why some women experience cyclical worsening of ADHD symptoms, or why symptoms intensify during hormonal transitions.

Many women are not diagnosed until perimenopause because earlier compensatory mechanisms become insufficient under changing hormonal conditions.

The vulnerability was present.

The physiological context changed.

Adult ADHD Symptoms: Cognitive Overload, Burnout, and Emotional Exhaustion

In adults, ADHD often presents less as visible hyperactivity and more as internal overload.

Common patterns include:

Persistent cognitive fatigue

Difficulty initiating low-stimulation tasks

Emotional reactivity under stress

High effort with inconsistent results

Many adults appear outwardly competent while internally exerting significant effort to maintain organization and follow-through.

That invisible effort is costly.

The mismatch between energy expenditure and output reflects regulatory strain — not a lack of discipline, resilience, or intelligence.

When executive systems operate near their threshold for extended periods, symptoms become more frequent and recovery becomes slower.

That is not character failure.

It is cumulative load.

Is ADHD Just a Dopamine Deficiency? The Story Is More Complex

Dopamine is often described as the central driver of ADHD, frequently simplified into a “motivation” or “reward” chemical. That explanation is partially true — but incomplete.

Dopamine signaling plays a central role in attention allocation, learning reinforcement, reward anticipation, and executive persistence. But ADHD cannot be reduced to low dopamine levels alone, nor explained by a single neurotransmitter pathway (19).

The brain does not operate on isolated chemicals. It operates on integrated networks.

Focusing exclusively on dopamine oversimplifies a much broader regulatory system that includes stress signaling, circadian rhythms, metabolic stability, inflammatory tone, and autonomic balance. Dopamine participates in that system — it does not control it independently.

What Dopamine Actually Does in ADHD: Reward, Motivation, and Effort

Dopamine helps regulate:

Signal-to-noise ratio in attention

Reward anticipation and behavioral reinforcement

Task initiation

Effort allocation over time

In ADHD, research suggests differences in dopamine transporter activity, receptor sensitivity, and signaling efficiency — particularly in frontostriatal pathways that connect the prefrontal cortex with reward-processing circuits (20).

This does not necessarily mean dopamine is “low.” It often means the system is less efficient or more context-dependent.

When a task is immediately rewarding or urgent, dopamine signaling increases and executive networks synchronize. When a task is delayed-reward, repetitive, or abstract, greater internal regulation is required to sustain engagement.

If sleep is compromised, stress is elevated, or energy delivery is unstable, that internal effort becomes harder to generate.

So dopamine influences prioritization — not raw intelligence.

Why ADHD Is Not Just About Dopamine

Attention and executive control rely on coordinated interaction between multiple neurotransmitter systems.

In addition to dopamine, ADHD involves altered regulation of:

Norepinephrine, which supports alertness, sustained attention, and working memory

Acetylcholine, which influences learning, focus, and cortical activation

GABA, which modulates inhibition and emotional regulation

These systems interact within larger physiological frameworks shaped by:

Cortisol rhythms and stress-axis regulation

Circadian timing

Glucose metabolism and mitochondrial ATP production

Inflammatory signaling and immune activation

When those foundational systems are unstable, dopamine signaling alone cannot compensate (21).

A person may have adequate dopamine availability — but if stress hormones are elevated, sleep is fragmented, or blood glucose is fluctuating, executive performance will still decline.

Neurotransmitters function within context.

Do ADHD Medications Fix the Root Cause? What They Help—and What They Don’t

Stimulant and non-stimulant medications primarily work by increasing synaptic availability of dopamine and norepinephrine, enhancing signaling efficiency in prefrontal networks. For many individuals, this improves focus, impulse control, and task initiation (22).

These effects are real and clinically meaningful.

However, medications do not directly address:

Brain energy production and mitochondrial efficiency

Chronic stress-axis dysregulation

Sleep and circadian instability

Inflammatory or metabolic contributors

Autonomic nervous system imbalance

This distinction matters.

Medication may improve signaling under existing physiological conditions. But if those underlying conditions remain unstable, symptom variability may persist. That helps explain why response patterns differ between individuals and why benefits sometimes fluctuate (43).

This is not an argument against medication.

It is an argument for understanding the full regulatory picture.

The Big Picture: ADHD Is a Regulation Problem With Multiple Inputs

Recognizing the limits of a dopamine-only narrative does not dismiss neurotransmitters or pharmacologic treatment. It contextualizes them.

ADHD reflects sensitivity to physiological load.

Neurotransmitter signaling matters — but it operates downstream of:

Energy availability

Nervous system tone

Sleep integrity

Hormonal balance

Inflammatory signaling

Environmental demand

When these inputs are stable, executive regulation improves.

When they are unstable, symptoms intensify — even if dopamine signaling is enhanced.

This systems-based framework explains why ADHD can improve in some contexts and deteriorate in others, and why long-term stability often requires more than symptom suppression.

It requires regulatory resilience.

Root Causes and Contributing Factors in ADHD

ADHD does not arise from a single cause, nor does it express itself through a single pathway. It reflects the interaction of multiple regulatory systems that govern energy production, stress adaptation, circadian rhythm, immune signaling, and executive network integration.

Symptoms often intensify when these systems are placed under sustained strain. What appears behaviorally as distractibility or impulsivity may physiologically reflect reduced prefrontal efficiency under cumulative load (23).

These contributors rarely operate in isolation. They interact, amplify one another, and shape how stable — or unstable — executive regulation feels on any given day.

Rather than long, disconnected lists, it is more clinically accurate to group these contributors into interconnected regulatory domains.

Autonomic Nervous System Dysregulation in ADHD: Sympathetic Dominance and Recovery

The autonomic nervous system governs arousal, focus, emotional reactivity, and recovery. It continuously shifts between sympathetic activation (mobilization) and parasympathetic restoration.

In ADHD, this system often remains biased toward heightened activation or rapid switching between states. The nervous system may oscillate between overstimulation and mental fatigue, with limited recovery time in between.

Chronic sympathetic dominance elevates cortisol, narrows attentional bandwidth, and reduces inhibitory control. Poor parasympathetic recovery impairs emotional regulation and increases cognitive reactivity (24).

When baseline arousal is elevated, sustaining calm, organized focus becomes harder.

This is not simply psychological stress.

It is altered physiological tone.

Circadian Misalignment in ADHD: Delayed Sleep Phase and Irregular Timing

Circadian rhythm synchronizes hormone release, neurotransmitter activity, and metabolic efficiency across the day.

Delayed sleep phase and irregular sleep timing are disproportionately common in individuals with ADHD. When internal circadian timing shifts later, executive performance often becomes misaligned with social or occupational demands.

Disrupted circadian rhythms impair:

Dopamine and norepinephrine balance

Working memory

Emotional resilience

Cognitive flexibility

Chronic misalignment reduces prefrontal efficiency and increases variability in attention regulation (25).

For many individuals, ADHD symptoms worsen not because the condition progressed — but because circadian stability deteriorated.

Blood Sugar Swings and ADHD: How Glucose Instability Affects Focus

The brain relies heavily on glucose and oxygen to sustain executive control. Prefrontal networks are especially sensitive to fluctuations in blood sugar.

When glucose levels rise rapidly and fall quickly — whether due to dietary patterns, stress hormones, or irregular eating — cognitive endurance declines.

Blood sugar instability can contribute to:

Increased distractibility

Reduced task persistence

Irritability

Midday cognitive crashes

Mitochondrial efficiency also plays a role. If ATP production is suboptimal, executive effort becomes more fatiguing (26).

What may appear as lack of discipline can reflect reduced metabolic stability.

Energy consistency supports attention consistency.

Gut–Brain Connection in ADHD: Microbiome, Inflammation, and Neurotransmitter Signaling

The gut is deeply integrated with brain function through immune, metabolic, and neurochemical pathways.

Gut microbes influence:

Dopamine and serotonin metabolism

Short-chain fatty acid production

Immune activation

Blood–brain barrier integrity

Disruptions in gut integrity or microbial balance can elevate inflammatory signaling and alter neurotransmitter modulation (27).

Gut dysfunction does not create ADHD independently. But in susceptible individuals, it can amplify regulatory instability by increasing neural noise and reducing signal clarity.

The brain and gut operate as a coordinated system.

Immune Activation and ADHD: How Inflammation Affects Executive Function

Low-grade inflammation influences synaptic plasticity, neurotransmission, and cortical network integration.

Chronic inflammatory signaling — whether driven by illness, environmental exposure, metabolic dysfunction, or immune activation — has been associated with impaired executive function and increased cognitive variability (28).

Inflammation increases neural energy demand while simultaneously reducing signaling efficiency.

That combination makes sustained attention more fragile.

ADHD symptoms may intensify during periods of infection, systemic inflammation, or chronic immune stress — not because motivation changed, but because neural regulation became metabolically more expensive.

Digital Overstimulation and Sensory Load: Why Modern Environments Worsen ADHD

Modern environments present unprecedented levels of sensory input and task switching.

Constant notifications, rapid content shifts, multitasking demands, and digital overstimulation increase dopaminergic spikes while reducing sustained attention training.

High-frequency stimulation conditions the brain toward novelty-seeking and reduces tolerance for low-stimulation tasks.

For individuals with ADHD — whose regulatory systems are already sensitive — this environmental load compounds instability.

Attention becomes externally driven rather than internally sustained.

Recovery time shrinks. Baseline arousal increases.

Regulatory fatigue accumulates.

The Cumulative Load Model: Why Multiple Small Stressors Create Big ADHD Symptoms

Each of these contributors may exert modest effects independently.

But executive regulation does not fail from a single input. It falters when total regulatory demand exceeds available recovery capacity.

Sleep disruption + chronic stress + blood sugar variability + inflammatory load + digital overstimulation may each seem manageable alone. Together, they create cumulative strain.

ADHD symptoms intensify not because of a singular root cause, but because the brain is operating near its regulatory threshold.

This systems-based model explains why:

Symptoms fluctuate

Labs may appear “normal”

Medication responses vary

Stress exacerbates dysfunction

Recovery restores stability

ADHD reflects sensitivity to cumulative physiological load — not a character flaw or isolated neurotransmitter deficit.

Why a Systems-Based Approach to ADHD Treatment Matters

When ADHD is viewed narrowly — as either a behavioral problem or a simple neurotransmitter imbalance — treatment often focuses on symptom suppression rather than regulatory stability.

Medication may increase focus. Behavioral strategies may improve organization. But neither framework alone fully explains why symptoms fluctuate, why progress plateaus, or why someone can perform exceptionally well in one context and struggle profoundly in another (29).

The missing piece is context.

A systems-based framework recognizes ADHD as a dynamic regulation condition shaped by interacting physiological inputs over time. Executive function is not static. It reflects the brain’s ability to maintain integration under changing metabolic, hormonal, emotional, and environmental demands.

When regulatory systems are stabilized, symptoms often soften.

When cumulative load increases, symptoms intensify.

This model does not replace conventional treatment.

It expands the lens.

Why ADHD Is Context-Dependent: Sleep, Stress, and Recovery Capacity

One of the defining features of ADHD is variability.

Attention, motivation, and executive function can improve or deteriorate based on:

Sleep quality

Stress exposure

Energy availability

Emotional demand

Environmental load

This variability is not random. It reflects the brain’s real-time regulatory capacity.

Prefrontal cortical efficiency depends on synchronized input from metabolic systems, circadian timing, autonomic tone, and stress signaling. When recovery capacity exceeds regulatory demand, executive function feels steady. When demand exceeds recovery capacity, symptoms intensify (30).

A systems-based model accounts for this fluidity rather than assuming ADHD should present as a fixed deficit.

Why ADHD Persists Even With “Normal” Labs

You may be told that your lab results are normal, their intelligence is intact, and their effort should be sufficient. Yet symptoms persist.

The disconnect arises because regulation depends on functional capacity — not simply reference ranges.

Stress-axis dysregulation, circadian misalignment, mitochondrial inefficiency, low-grade inflammation, and subtle glucose instability may all exist within “normal” laboratory parameters. Individually, these may appear insignificant. Collectively, they can meaningfully impair executive regulation (31).

Standard labs identify disease thresholds.

Executive function depends on optimal thresholds.

This distinction explains why symptoms can persist despite technically normal findings.

ADHD Treatment Goals: Regulation Stability, Not Just Symptom Control

A systems-based perspective does not reject diagnostic criteria, cognitive-behavioral strategies, or pharmacologic treatment. Instead, it reframes the treatment goal.

Rather than asking, “How do we suppress symptoms?” the more productive questions become:

What is increasing regulatory demand?

What is reducing recovery capacity?

What destabilizes executive function in this individual?

What restores consistency rather than temporary focus?

The objective shifts from short-term performance enhancement to long-term regulatory stability (32).

That may include:

Sleep restoration

Stress modulation

Metabolic stabilization

Autonomic recalibration

Inflammatory load reduction

Strategic medication when appropriate

The emphasis is not on replacing existing treatments, but on strengthening the foundation upon which they operate.

What a Systems-Based Evaluation Considers

Rather than isolating attention as the sole problem, a systems-based approach evaluates the interaction of multiple domains, including:

Nervous system tone and stress signaling

Sleep architecture and circadian rhythm integrity

Metabolic efficiency and glucose stability

Mitochondrial function and energy production

Inflammatory and immune inputs

Environmental and sensory load

This integrative lens explains symptom patterns that otherwise appear inconsistent or resistant to conventional strategies (62).

It recognizes that ADHD symptoms may represent the visible edge of a deeper regulatory equation.

ADHD Summary: The Regulation Model in Plain English

ADHD is not a lack of attention.

It is a variability of regulation.

It reflects how consistently the brain can sustain executive function under internal and external demand.

Across this article, several themes emerge:

Attention in ADHD is context-dependent, not absent

Executive function fluctuates with sleep, stress, metabolic stability, and inflammatory tone

Dopamine matters — but it operates within larger physiological systems

Symptoms intensify when regulatory demand exceeds recovery capacity

This model explains why ADHD looks different across individuals and life stages. It explains why symptom expression changes under stress, illness, hormonal shifts, or sleep disruption. And it clarifies why narrow explanations often fall short.

When ADHD is understood as a regulation condition, treatment becomes more precise — and more humane.

When to Seek an ADHD Root-Cause Evaluation

If attention difficulties, cognitive fatigue, emotional reactivity, or executive dysfunction have been persistent, unpredictable, or resistant to conventional strategies, it may be time to look beyond surface-level symptom management.

ADHD that fluctuates significantly with stress, sleep disruption, hormonal shifts, illness, or burnout often signals regulatory instability rather than a simple focus deficit.

A systems-based evaluation asks different questions:

Is sleep architecture contributing to executive fatigue?

Is chronic stress altering cortisol rhythm and prefrontal efficiency?

Is blood sugar variability affecting cognitive endurance?

Is inflammatory load increasing neural noise?

Is autonomic tone impairing sustained regulation?

Rather than treating attention as an isolated symptom, this approach identifies what is increasing regulatory demand and what is limiting recovery capacity.

For some, medication remains an important part of care. For others, stabilizing sleep, stress signaling, metabolic support, or nervous system tone meaningfully shifts symptom intensity and consistency.

The goal is not simply improved focus for a few hours.

The goal is more stable regulation over time.

→ Acupuncture & Nervous System Regulation

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Key Clinical Insights on ADHD as a Regulation Disorder

ADHD is not defined by distraction alone. It reflects variability in how consistently the brain can regulate executive function under changing physiological conditions.

Across research and clinical observation, several patterns emerge:

Executive dysfunction in ADHD is context-sensitive, not constant

Symptom intensity increases when sleep, stress signaling, or metabolic stability decline

Dopamine signaling differences exist, but operate within broader regulatory systems

Hyperfocus reflects intact attentional capacity under strong reward activation

Burnout, illness, and circadian disruption frequently amplify symptoms

“Normal” labs do not rule out functional regulatory strain

Understanding ADHD through a regulation model shifts the goal of care. Instead of asking, “Why can’t you focus?” the more useful question becomes:

What is increasing regulatory load?

When physiological strain exceeds recovery capacity, executive control becomes inconsistent. When foundational systems are stabilized, attention often improves as a downstream effect.

This framework does not deny the validity of diagnosis. It clarifies why symptoms fluctuate, why medication response varies, and why sustainable improvement often requires looking beyond neurotransmitters alone.

Frequently Asked Questions About ADHD

Is ADHD a lack of attention or a regulation disorder?

ADHD is more accurately described as a regulation disorder rather than a true lack of attention. Most people with ADHD can focus intensely in certain contexts but struggle to regulate attention consistently across tasks and environments. The core issue is variability in executive function and nervous system stability, not an absence of ability.

Why do ADHD symptoms fluctuate from day to day?

ADHD symptoms fluctuate because executive function depends on sleep quality, stress levels, metabolic stability, and overall recovery capacity. When these systems are stable, focus and impulse control improve. When they are strained, symptoms intensify — even if motivation remains high.

Can stress make ADHD worse?

Yes. Chronic stress directly impairs prefrontal cortical function and increases cortisol signaling, which weakens executive control and emotional regulation. During periods of prolonged stress or burnout, ADHD symptoms often become more pronounced because regulatory resources are depleted.

Does sleep affect ADHD symptoms?

Sleep has a major impact on ADHD symptoms. Inadequate or disrupted sleep reduces dopamine and norepinephrine signaling efficiency and impairs executive function. Even mild chronic sleep deprivation can significantly worsen inattention, irritability, and cognitive fatigue.

Is ADHD caused by a dopamine deficiency?

ADHD cannot be fully explained by dopamine deficiency alone. While dopamine signaling plays an important role in attention and reward processing, ADHD involves multiple interacting systems, including stress hormones, circadian rhythm, metabolic stability, and inflammatory signaling.

Why can people with ADHD hyperfocus on some tasks but not others?

People with ADHD can hyperfocus when a task is novel, urgent, or personally meaningful because reward signaling increases and executive networks synchronize. Routine or delayed-reward tasks require more sustained internal regulation, which is where inconsistency tends to appear.

Can ADHD exist without hyperactivity?

Yes. Many adults experience primarily inattentive ADHD without visible hyperactivity. This presentation often includes cognitive fatigue, disorganization, emotional reactivity, and difficulty sustaining focus rather than outward restlessness.

Why do ADHD symptoms get worse in adulthood?

ADHD often feels worse in adulthood because regulatory demands increase while external structure decreases. Career pressure, chronic stress, sleep disruption, and hormonal shifts can exceed the brain’s recovery capacity, making symptoms more visible.

Can inflammation or physical health issues affect ADHD?

Inflammation, metabolic instability, sleep disruption, and autonomic nervous system dysregulation can amplify ADHD symptoms. These factors do not create ADHD independently, but they can reduce executive stability and increase symptom variability.

Is ADHD a lifelong condition?

ADHD is not static. While the underlying regulatory sensitivity may persist, symptom intensity can improve or worsen depending on sleep, stress load, hormonal changes, metabolic health, and environmental demands. Regulation stability often determines how ADHD presents over time.

Resources

World Psychiatry – The World Federation of ADHD international consensus statement

Annual Review of Psychology – Executive control, self-regulation, and attention

The Lancet – Attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

American Psychiatric Association – Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5-TR)

Annual Review of Psychology – Executive functions and self-regulation

Nature Reviews Neuroscience – Executive functions and the prefrontal cortex

Biological Psychiatry – Large-scale brain systems in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder

Trends in Cognitive Sciences – The neural basis of cognitive control

Annual Review of Clinical Psychology – Systems-based models of mental health

Clinical Psychology Review – Contextual and dimensional models of psychopathology

Cell Metabolism – Brain energy demand and cognitive function

Frontiers in Neuroscience – Brain energy metabolism and cognitive performance

Nature Neuroscience – Stress signalling pathways that impair prefrontal cortex function

Sleep Medicine Reviews – Sleep and executive function

Development and Psychopathology – ADHD across developmental stages

Journal of Clinical Psychology – Adult ADHD presentation and burnout

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Chronic stress and executive regulation

Chronobiology International – Circadian rhythm disruption in adult ADHD

Neuropharmacology – Dopamine signaling and attention

Trends in Neurosciences – Dopamine and reward-based learning

Nature Reviews Neuroscience – Norepinephrine and prefrontal cortex function

American Journal of Psychiatry – Pharmacological treatment of ADHD

Annual Review of Clinical Psychology – Multisystem contributors to cognitive regulation

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews – Autonomic nervous system regulation and cognition

Journal of Sleep Research – Sleep architecture and cognitive performance

Brain Research – Energy metabolism and attention regulation

Gut Microbes – The gut–brain axis and cognitive function

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity – Inflammation and cognitive performance

Integrative Medicine Research – Whole-systems approaches to cognitive regulation

Cognitive Neuroscience – Variability and context-dependent attention

Frontiers in Psychology – Functional capacity versus reference ranges in cognition

Annual Review of Psychology – Regulation, resilience, and adaptive capacity