The Most Common Nutrient Deficiencies—and Why They’re Often Missed

How medications, gut dysfunction, inflammation, and modern diets drive overlooked deficiencies

Nutrient deficiencies are common in modern clinical practice, yet they are frequently underrecognized and inadequately evaluated (1). This is not solely a consequence of poor dietary choices. In many cases, deficiencies develop despite seemingly adequate intake and routine medical care.

Nutrient sufficiency is determined by more than what is consumed. Digestive capacity, gut integrity, medication use, inflammatory burden, metabolic demand, and environmental exposures all influence how nutrients are absorbed, utilized, and retained at the cellular level. When these systems are disrupted, functional deficiencies can emerge even when standard laboratory values fall within reference ranges (2).

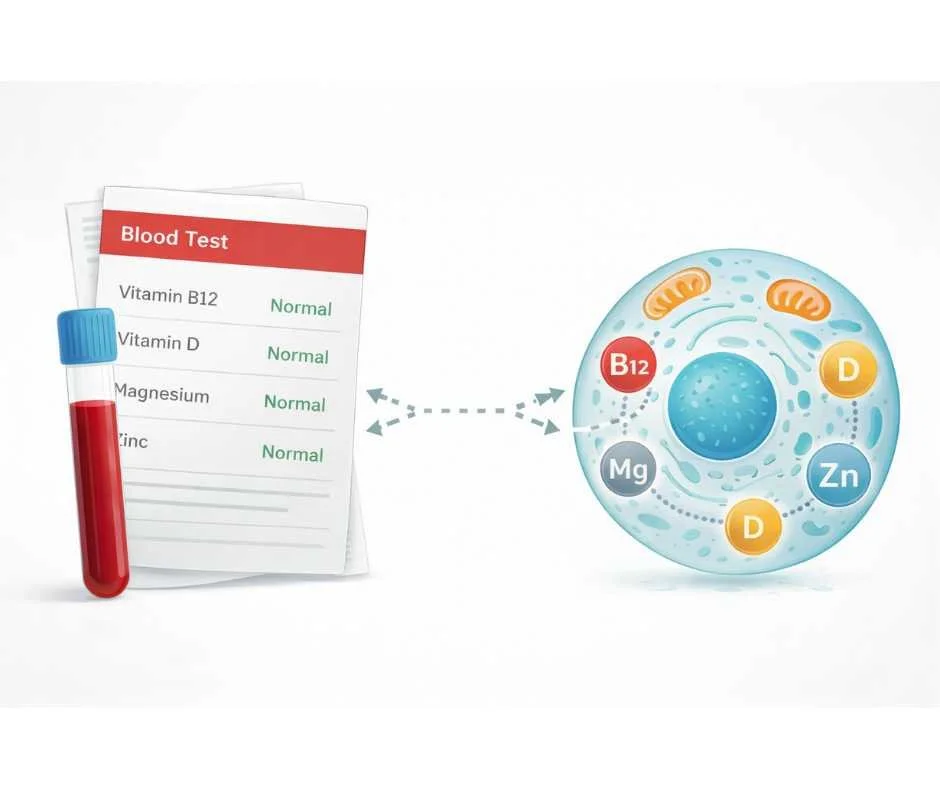

This helps explain why individuals may follow dietary guidelines, take supplements, and still experience signs of insufficiency—or why conventional testing may fail to identify meaningful nutrient gaps. Serum measurements reflect circulating levels at a single point in time, but they do not reliably assess tissue-level availability or increased physiological demand.

Many people experiencing nutrient deficiency symptoms are told their labs are normal, yet normal blood tests can miss functional nutrient deficiencies that only become apparent with cellular or functional nutrient testing.

Modern conditions further compound this problem. Changes in agricultural practices have reduced the micronutrient density of many foods, while chronic stress, inflammation, and environmental exposures increase nutrient requirements (3). Medications and gastrointestinal dysfunction can quietly impair absorption or alter nutrient metabolism, often without producing immediate or obvious symptoms.

For these reasons, nutrient deficiencies are best understood as systems-based issues, not isolated dietary failures. Identifying why deficiencies develop—and why they are often missed—requires evaluating intake, absorption, utilization, and demand together, rather than relying on symptoms or single lab values alone.

In this article, we examine the most common nutrient deficiencies, the mechanisms that contribute to their development, and the reasons they frequently go undetected in standard care.

“Optimal nutrition is the medicine of tomorrow.”

— Linus Pauling

Why Nutrient Deficiencies Are So Common Today

Nutrient deficiencies are not an anomaly of modern health—they are a predictable consequence of increased physiological demand occurring alongside reduced nutrient availability and impaired utilization (4).

While dietary intake remains relevant, it is only one variable in a much larger equation. In clinical practice, nutrient sufficiency is determined by the interaction between intake, absorption, metabolic demand, and regulatory stress. When these factors are misaligned, deficiencies develop even in individuals who appear to be eating well.

Intake Alone Does Not Define Sufficiency

Dietary guidelines and recommended daily allowances were developed to prevent overt deficiency diseases, not to define optimal nutrient status for immune regulation, mitochondrial function, hormone signaling, or detoxification capacity (5). These population-based estimates do not account for age-related changes, chronic stress, inflammation, medication use, or individual variability in metabolism.

As a result, individuals may meet general dietary recommendations while remaining functionally deficient at the tissue level.

Declining Nutrient Density in the Food Supply

Changes in agricultural practices have altered the micronutrient content of many foods. Soil depletion, crop selection for yield rather than mineral content, and food processing have collectively reduced the concentration of essential vitamins and minerals compared to historical baselines (6).

Even diets rich in whole foods may fail to provide adequate micronutrient support when physiological demand is elevated.

Increased Demand From Stress, Inflammation, and Environmental Load

Chronic stress, immune activation, and environmental exposures place sustained demands on antioxidant systems, detoxification pathways, and mitochondrial energy production. These processes are micronutrient-dependent, increasing overall nutrient requirements even in the absence of dietary change (7).

When demand increases without proportional replenishment—or when absorption and utilization are impaired—nutrients are diverted toward short-term survival processes, leaving other systems under-supported.

Absorption and Utilization Are Commonly Disrupted

Adequate intake does not guarantee adequacy at the cellular level. Gastric acid production, bile flow, intestinal integrity, transporter function, and enzymatic activity all influence whether nutrients reach target tissues. Medications, gastrointestinal dysfunction, dysbiosis, and chronic inflammation frequently interfere with these processes (8).

For these reasons, nutrient deficiencies are best understood as systems-level disruptions, not simple dietary shortcomings.

Why Nutrient Deficiencies Are Often Missed on Standard Lab Testing

One of the primary reasons nutrient deficiencies persist is not lack of awareness, but limitation of assessment. Conventional laboratory testing is designed to identify overt disease states rather than early or functional insufficiency (9).

Most standard tests measure circulating serum levels at a single point in time. While these values can identify severe deficiency, they do not reliably reflect tissue-level availability, intracellular utilization, or increased physiological demand (10).

Serum Levels Do Not Reflect Functional Sufficiency

Serum measurements indicate what is present in the bloodstream, not what is reaching cells where nutrients are required for mitochondrial energy production, immune regulation, hormone signaling, and detoxification. The body actively regulates blood concentrations, often maintaining values within reference ranges even when tissues are under-supplied (11).

As a result, functional nutrient depletion can exist long before laboratory values fall outside of “normal” limits.

Increased Demand Is Often Overlooked

Nutrient deficiency does not always reflect inadequate intake. In many cases, physiological demand has increased due to chronic stress, inflammation, immune activation, medication use, or environmental exposure. Under these conditions, nutrients are consumed more rapidly or diverted into protective pathways, reducing availability for other metabolic processes (12).

Standard laboratory testing does not account for this increased demand, leading to false reassurance when values appear acceptable.

Absorption and Utilization Are Rarely Evaluated

Digestive capacity, gut integrity, enzymatic activity, and transporter function all influence whether nutrients are absorbed and utilized effectively. Gastrointestinal dysfunction, hypochlorhydria, dysbiosis, and medication effects can significantly impair assimilation without producing clear abnormalities on routine serum testing (13).

When absorption or utilization is compromised, increasing intake alone does not resolve deficiency—and standard labs often fail to reveal the underlying issue.

Functional Testing Provides a Broader Clinical Context

Functional and micronutrient testing evaluates nutrient status at the cellular level and considers patterns of insufficiency within the context of metabolic stress, toxic burden, and regulatory demand (14). This broader perspective allows deficiencies to be identified earlier and interpreted more accurately than isolated serum values alone.

For individuals with complex health patterns, chronic stress exposure, or long-term medication use, this approach is often necessary to identify clinically meaningful nutrient imbalances.

Nutrients Commonly Affected by Modern Diets, Absorption Issues, and Metabolic Stress

Rather than isolated deficiencies, modern clinical patterns more often reflect clusters of nutrient insufficiency driven by impaired absorption, increased metabolic demand, inflammatory burden, and regulatory disruption. Certain nutrients are particularly vulnerable within this context and appear repeatedly in functional assessment.

Magnesium (High Demand, Often Underrecognized)

Magnesium plays a central role in energy metabolism, neuromuscular signaling, glucose regulation, and stress response. Insufficiency is common due to reduced dietary intake, soil depletion, increased losses from chronic stress, and medication use. Despite its importance, magnesium status is frequently underrecognized because serum levels are tightly regulated and may not reflect intracellular availability (15).

As a key cofactor, magnesium also influences the activation and utilization of other nutrients, including vitamin D.

Vitamin D (Widespread Insufficiency)

Vitamin D insufficiency is consistently observed across populations and is influenced by limited sun exposure, indoor lifestyles, geographic factors, age-related changes in synthesis, and impaired absorption of fat-soluble nutrients (16). Because vitamin D functions as a hormone precursor involved in immune regulation, neuromuscular signaling, and calcium metabolism, inadequate status can reflect broader regulatory strain rather than simple intake failure.

Interpretation of vitamin D status should consider absorption, storage, cofactor availability, and metabolic demand rather than relying on a single value in isolation.

B Vitamins (Demand, Absorption, and Interdependence)

B vitamins function as interconnected pathways supporting mitochondrial energy production, neurotransmitter synthesis, methylation, and detoxification. Functional insufficiency often reflects increased demand from chronic stress or inflammation, impaired absorption related to gastrointestinal dysfunction, or medication effects rather than inadequate intake alone (17).

Vitamin B12 is particularly sensitive to disruptions in stomach acid production and intrinsic factor availability, making insufficiency more likely in individuals with gastrointestinal disorders or long-term use of certain medications.

Iron Dysregulation (Utilization and Regulation)

Iron status is frequently mischaracterized as a simple deficiency problem. In many cases, iron is present but poorly utilized due to inflammatory signaling, immune activation, gastrointestinal dysfunction, or impaired regulation. These factors can limit tissue availability independent of intake (18).

For this reason, iron-related concerns are best understood within a broader regulatory context rather than addressed through intake alone.

Zinc (Absorption and Immune Demand)

Zinc is essential for immune signaling, epithelial integrity, and enzymatic activity. Insufficiency may develop in the setting of gastrointestinal dysfunction, chronic inflammation, or increased immune demand. Because zinc absorption occurs primarily in the small intestine, disruptions in gut health can significantly affect status even when dietary intake appears adequate (19).

Key Clinical Pattern

Across these nutrients, a common theme emerges: deficiency is rarely the result of intake alone. Instead, insufficiency reflects the interaction between dietary availability, digestive and absorptive capacity, metabolic demand, inflammatory burden, and cofactor relationships.

This pattern underscores why identifying nutrient issues requires more than symptom recognition or isolated lab values.

How Nutrient Deficiencies Should Be Evaluated (Testing Before Treatment)

Because nutrient insufficiency is rarely driven by intake alone, evaluation must extend beyond symptoms and basic laboratory panels. Effective assessment considers where nutrients fail—at intake, absorption, utilization, or regulation—rather than assuming a single point of breakdown.

Why Symptoms Alone Are Not a Reliable Guide

Symptoms associated with nutrient insufficiency are often non-specific and overlapping. Fatigue, cognitive changes, immune shifts, and metabolic disturbances can reflect multiple underlying processes, including inflammation, hormonal dysregulation, mitochondrial stress, or impaired absorption. Relying on symptoms alone makes it difficult to determine which nutrients are involved—or whether nutrient imbalance is a primary driver or a downstream effect.

Limitations of Conventional Blood Testing

Standard laboratory panels are designed to detect severe deficiency states and overt disease. Most assess circulating serum levels at a single point in time. While useful for identifying advanced deficiency, these values do not reliably reflect intracellular availability, functional utilization, or increased physiological demand.

Nutrients are required inside the cell, where they support mitochondrial energy production, enzymatic reactions, immune signaling, hormone metabolism, and detoxification pathways. The bloodstream functions primarily as a transport compartment. The body tightly regulates serum concentrations to preserve short-term stability, which means blood values may remain within reference ranges even when cells are under-supplied.

As a result, clinically meaningful nutrient insufficiency can persist long before abnormalities appear on routine blood work.

Absorption, Utilization, and Demand Are Rarely Captured

Digestive capacity, gut integrity, bile flow, enzymatic activity, and transporter function all influence whether nutrients are absorbed and made available to tissues. Gastrointestinal dysfunction, chronic inflammation, medication use, and metabolic stress can impair intracellular uptake or accelerate nutrient depletion without producing obvious changes in serum levels.

In these situations, increasing intake alone does not resolve deficiency, and standard testing often fails to reveal the underlying problem.

The Role of Functional and Cellular-Level Assessment

Functional and micronutrient testing evaluates nutrient status at the cellular level, where nutrients are actually utilized. This approach provides insight into how nutrients are being absorbed, retained, and used within tissues, rather than relying solely on what is circulating in the blood.

By interpreting nutrient status in the context of metabolic demand, inflammatory burden, and cofactor relationships, cellular-level assessment allows deficiencies to be identified earlier and understood more accurately than isolated serum values alone.

→ Advanced Functional Lab Testing

Why Evaluation Must Precede Correction

Targeted intervention is most effective when it follows comprehensive assessment. Addressing nutrient imbalance without understanding intracellular availability, absorption barriers, and cofactor dependencies can lead to incomplete results or unintended imbalance elsewhere.

Testing before treatment allows nutrient correction to be precise, proportional, and aligned with the broader physiological context—supporting restoration rather than temporary compensation.

Why Nutrient Deficiencies Persist Despite “Normal” Labs and Supplement Use

Nutrient deficiencies rarely occur in isolation, and they are seldom explained by diet alone. In modern clinical patterns, insufficiency most often reflects a mismatch between intake, absorption, intracellular utilization, metabolic demand, and cofactor availability—factors that standard evaluation frequently fails to capture.

This is why nutrient issues persist despite “normal” labs, well-intentioned supplementation, or adherence to general dietary guidelines. When nutrients are not reaching the cell, or cannot be effectively utilized once there, replacement alone does not resolve the underlying problem.

A systems-based approach shifts the focus from guessing or blanket supplementation to understanding why deficiencies develop and where regulation is breaking down. By evaluating nutrient status at the cellular level and interpreting findings within the broader physiological context, correction becomes more precise, safer, and more durable.

Addressing nutrient imbalances effectively requires moving beyond symptoms and isolated lab values toward a comprehensive assessment of how the body is functioning as an integrated system.

When Deeper Nutrient Evaluation Is Clinically Warranted

If you are experiencing persistent symptoms, have a history of digestive issues, chronic stress, inflammation, or long-term medication use, a deeper evaluation of nutrient status may be warranted.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Nutrient Deficiencies

Why are nutrient deficiencies often missed?

Nutrient deficiencies are often missed because standard blood tests measure nutrients circulating in the bloodstream, not what is available inside cells. The body tightly regulates blood levels, which can mask underlying cellular insufficiency until depletion becomes more advanced.

Can you have nutrient deficiencies even if you eat a healthy diet?

Yes. Nutrient sufficiency depends on digestion, absorption, cellular uptake, inflammation, medication use, metabolic demand, and cofactor availability—not diet alone.

Why do blood tests look normal when nutrient deficiencies are suspected?

Routine blood tests are designed to detect severe deficiency states. They do not reliably reflect intracellular nutrient availability or functional demand, allowing deficiencies to persist despite “normal” results.

What is the difference between serum testing and cellular micronutrient testing?

Serum testing measures nutrients in the blood at a single point in time. Cellular micronutrient testing evaluates nutrient status closer to where nutrients are actually used—inside cells—providing a more functional view.

Can medications cause nutrient deficiencies?

Yes. Certain medications can impair absorption, alter metabolism, or increase nutrient losses over time, contributing to deficiencies even when dietary intake appears adequate.

Can gut problems cause nutrient deficiencies?

Yes. Low stomach acid, bile flow issues, dysbiosis, and intestinal inflammation can significantly impair nutrient absorption and utilization.

Why do nutrient deficiencies often occur together?

Many nutrients function in interconnected pathways and depend on cofactors. When absorption or regulation is disrupted, multiple nutrients are often affected simultaneously.

Why do cofactors matter when correcting nutrient deficiencies?

Cofactors are required for many nutrients to be activated and utilized effectively. Without them, replacing a single nutrient may not correct the deficiency and can sometimes create imbalance.

Is it possible to take supplements and still be deficient?

Yes. Impaired absorption, missing cofactors, inappropriate dosing, or increased metabolic demand can prevent supplements from restoring intracellular sufficiency.

What is the safest way to address suspected nutrient deficiencies?

The safest approach is to evaluate nutrient status in context—considering intake, absorption, utilization, demand, and cofactor relationships—before initiating correction.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Nutrients – Global prevalence of micronutrient deficiencies and implications for health

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition – Functional indicators of nutrient status beyond dietary intake

Journal of Nutrition – Effects of modern agricultural practices on micronutrient density of foods

Physiological Reviews – Stress, inflammation, and micronutrient demand in human health

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine – Dietary reference intakes: Applications in clinical practice

Clinical Chemistry – Limitations of serum biomarkers for assessing micronutrient status

Journal of Internal Medicine – Inflammation-mediated alterations in micronutrient metabolism

Journal of Trace Elements in Medicine and Biology – Magnesium deficiency: Mechanisms, assessment, and clinical relevance

Nutrients – Functional B-vitamin deficiencies and medication-related depletion

Nutrients – Zinc absorption, immune demand, and gastrointestinal influences