How the Immune System Works: Innate vs. Adaptive Immunity Explained

Understanding immune regulation, inflammation, and immune balance before chronic illness develops

The immune system is often described as something that needs to be “boosted,” strengthened, or activated. In reality, immune health has far less to do with intensity and far more to do with regulation, coordination, and timing (1).

A well-functioning immune system does not stay permanently switched on. It responds appropriately to threats, resolves inflammation once the job is done, and maintains tolerance to the body’s own tissues and harmless exposures. When this regulatory balance breaks down, immune symptoms can appear long before a formal diagnosis is ever made (2).

Many people experiencing frequent infections, prolonged recovery, chronic inflammation, autoimmune patterns, or persistent symptoms despite “normal” lab results are not dealing with weak immunity. More often, they are dealing with immune miscommunication—where different parts of the immune system are out of sync, overactivated, or unable to shut down appropriately.

To understand why this happens, it is essential to first understand how the immune system is designed to work.

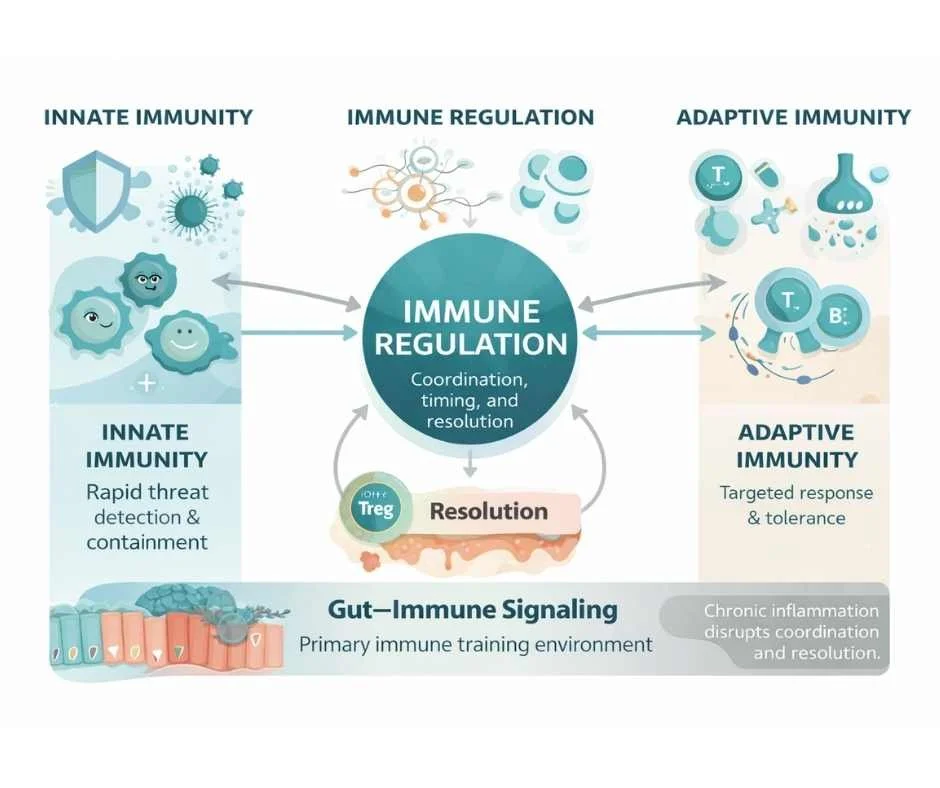

At a foundational level, human immunity is organized into two interconnected branches: innate immunity and adaptive immunity. These systems serve different roles, operate on different timelines, and rely on precise coordination to protect the body effectively without causing collateral damage.

This article explains how these two arms of the immune system function, how they interact with inflammation and metabolic signaling, and why immune regulation—not immune stimulation—is the key to long-term immune resilience and disease prevention.

Understanding Innate and Adaptive Immunity

The human immune system is not a single, uniform defense mechanism. It is a coordinated network of systems designed to recognize threats, respond appropriately, and restore balance once the threat has passed. At the most fundamental level, immune function is organized into two interconnected arms: innate immunity and adaptive immunity.

Each serves a distinct role. Neither is optional. And dysfunction rarely involves just one in isolation.

Innate Immunity: The First-Line Defense System

Innate immunity is the body’s immediate, non-specific defense system. It is present from birth and responds within minutes to hours of a perceived threat (3).

Key components of innate immunity include:

Physical barriers such as the skin and mucosal surfaces

Immune cells like macrophages, neutrophils, dendritic cells, and natural killer (NK) cells

Inflammatory signaling molecules that recruit immune activity to affected tissues

The primary job of the innate immune system is threat detection and containment. It recognizes patterns associated with danger—such as pathogens, toxins, or tissue injury—and initiates an inflammatory response to prevent further harm (4).

Importantly, innate immunity is closely tied to inflammation. When functioning properly, this inflammatory response is short-lived and resolves once the threat is neutralized. When regulation fails, innate immune activation can persist, creating a state of chronic inflammatory signaling that places continuous stress on the immune system and surrounding tissues.

Adaptive Immunity: Precision, Memory, and Immune Tolerance

Adaptive immunity is the body’s specialized, learned immune response. Unlike innate immunity, it develops over time and is shaped by prior exposures (5).

Core components of adaptive immunity include:

T lymphocytes (T cells), which coordinate immune responses and regulate immune activity

B lymphocytes (B cells), which produce antibodies

Immune memory, allowing faster and more precise responses to previously encountered threats

The adaptive immune system is responsible for targeted defense. Rather than responding broadly, it identifies specific antigens and mounts a precise response designed to eliminate the threat while minimizing collateral damage.

Just as important as attack is tolerance. A healthy adaptive immune system learns what not to react to—such as the body’s own tissues, food proteins, and harmless environmental exposures (6). Loss of this tolerance is a defining feature of autoimmune disease, but the breakdown often begins long before a diagnosis is made.

Why Balance Between Innate and Adaptive Immunity Matters

Innate and adaptive immunity are not separate silos. They are deeply interdependent.

Innate immunity initiates the immune response and provides the signals that guide adaptive immunity

Adaptive immunity refines the response and helps shut down inflammation once the threat is resolved

Problems arise when this coordination breaks down.

In some cases, the innate immune system remains chronically activated, driving ongoing inflammation without effective resolution. In others, adaptive immunity fails to respond appropriately, leading to recurrent infections, poor immune memory, or immune exhaustion. In more complex patterns, both systems are active—but misaligned—resulting in persistent symptoms despite apparently “normal” immune markers.

Understanding this balance is critical, because many modern immune-related conditions are not caused by a lack of immune activity, but by disrupted immune signaling and regulation (7).

Immune Regulation, Not Immune Stimulation

This distinction is essential: a healthy immune system does not need to be constantly stimulated. It needs to be appropriately regulated.

Effective immune health depends on:

Timely activation

Accurate threat recognition

Controlled inflammatory signaling

Proper resolution and return to baseline

When these processes are supported, immune resilience improves naturally. When they are disrupted, immune symptoms may persist or escalate—often without a clear explanation on standard testing.

In the next section, we will examine how chronic inflammatory signaling and metabolic stress interfere with immune regulation, and why immune dysfunction so often develops gradually rather than suddenly.

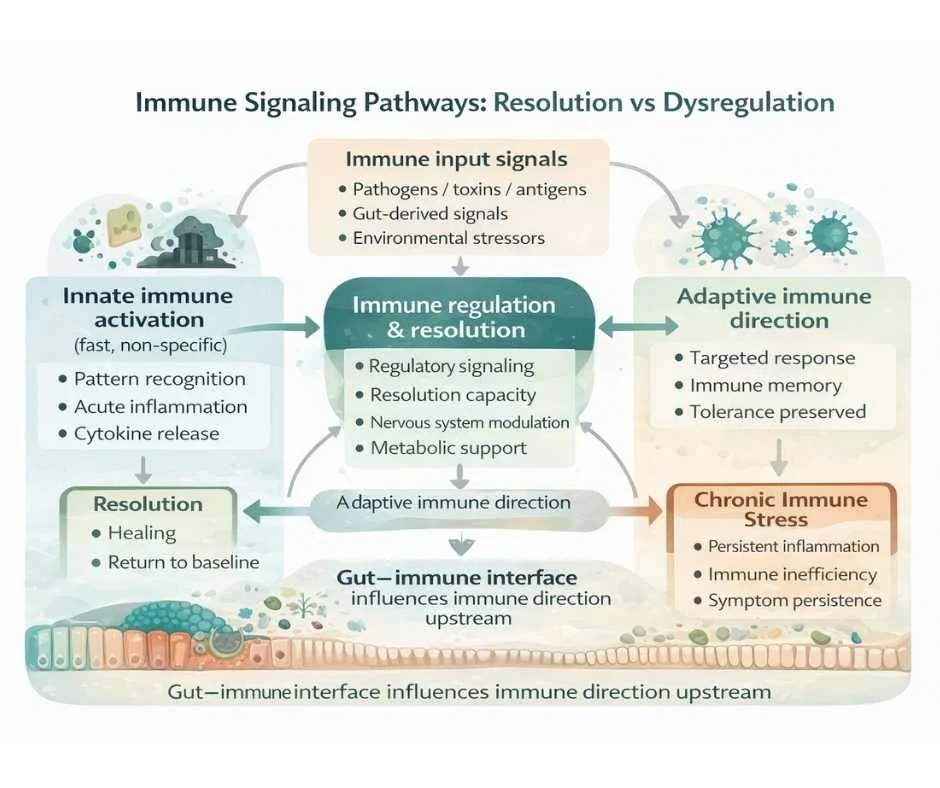

How Chronic Inflammatory Signaling Disrupts Immune Regulation

Under healthy conditions, inflammation is a temporary and tightly controlled process. It is activated by the innate immune system to address a threat and then deliberately resolved once that threat has been managed. Immune balance depends not only on the ability to mount an inflammatory response, but on the body’s capacity to turn that response off (8).

Problems arise when inflammatory signaling does not fully resolve.

Chronic, low-grade inflammation places the immune system in a constant state of alert. Innate immune cells continue to signal danger, even when no active infection or injury is present. Over time, this persistent activation begins to interfere with coordination between the innate and adaptive arms of the immune system (9,10).

Rather than improving immune protection, this pattern erodes immune efficiency.

Immune Overactivation Is Not Immune Strength

One of the most common misconceptions about immunity is that more immune activity equals better protection. In reality, chronic immune activation often leads to poorer immune outcomes.

When the innate immune system remains continuously stimulated:

Inflammatory cytokines stay elevated

Tissue repair and resolution pathways are suppressed

Adaptive immune responses become dysregulated

Immune signaling becomes noisy and less precise

This can manifest clinically as frequent infections, prolonged recovery, heightened sensitivity to environmental exposures, or symptoms that fluctuate without a clear trigger.

At the same time, adaptive immunity may struggle to generate effective immune memory or appropriate tolerance. The result is an immune system that appears busy—but is functionally inefficient. (11)

Why Immune Symptoms Can Exist Without “Abnormal” Labs

Many individuals experiencing immune-related symptoms are told their immune system looks “normal” on standard blood work. This disconnect often occurs because immune regulation is a functional process, not simply a matter of cell counts or antibody levels.

Routine labs may not capture:

Persistent inflammatory signaling at the tissue level

Impaired immune resolution

Dysregulated communication between immune cells

Shifts in immune tolerance or immune exhaustion

As a result, immune dysfunction may be present long before it is detectable through conventional testing. This is why immune-related conditions often develop gradually, with subtle symptoms preceding more defined diagnoses. (12)

Immune Dysfunction Develops Over Time

Immune imbalance rarely appears overnight.

It typically reflects a cumulative burden on immune regulation, influenced by factors such as:

Repeated immune triggers

Ongoing inflammatory exposure

Metabolic stress

Disrupted gut–immune signaling

Chronic nervous system activation

As these stressors accumulate, the immune system adapts in ways that are initially protective—but ultimately become maladaptive when resolution pathways are overwhelmed.

Understanding this progression is critical, because it reframes immune health as something that can be supported and restored, rather than simply suppressed or stimulated. (13)

Everyday Signals That Shape Immune Regulation

Immune function does not operate in isolation. It is continuously influenced by signals coming from the nervous system, metabolic state, circadian rhythms, and the external environment. These inputs help determine whether the immune system remains adaptable and responsive—or becomes chronically activated and inefficient.

Rather than acting as isolated “health habits,” factors such as sleep, movement, light exposure, and stress serve as regulatory signals that inform immune behavior at a cellular level.

Sleep and Circadian Rhythm as Immune Regulators

Sleep is one of the most powerful modulators of immune function. During deep, restorative sleep, the immune system shifts toward repair, regulation, and resolution of inflammatory signaling.

When sleep is disrupted or circadian rhythms are misaligned:

Pro-inflammatory signaling increases

Immune resolution pathways are impaired

Adaptive immune memory becomes less efficient

Recovery from infections is delayed

Over time, insufficient or irregular sleep can push the immune system toward a state of chronic vigilance, making it harder to distinguish between real threats and benign stimuli. (14)

Movement as an Immune-Modulating Signal

Regular movement provides the immune system with important feedback about tissue health, circulation, and metabolic demand. Moderate, consistent physical activity helps support immune surveillance while promoting anti-inflammatory signaling.

However, immune regulation depends on appropriate intensity and recovery. Excessive training, under-recovery, or prolonged sedentary behavior can all disrupt immune balance—either by increasing inflammatory stress or by reducing immune responsiveness.

The immune system responds best to movement patterns that are sustainable and well-matched to an individual’s metabolic and nervous system capacity. (15)

Stress, the Nervous System, and Immune Communication

The immune system is tightly connected to the nervous system through hormonal and neurochemical signaling pathways. When stress becomes chronic, these signals begin to shift immune behavior.

Persistent activation of stress pathways can:

Amplify inflammatory signaling

Suppress adaptive immune precision

Reduce immune tolerance

Interfere with proper immune resolution

This is one reason immune symptoms often worsen during periods of emotional strain, illness, poor sleep, or cumulative life stress—even in the absence of a new trigger. (16)

Environmental Load and Immune Capacity

The immune system also responds continuously to environmental inputs, including air quality, dietary exposures, microbial balance, and chemical load. While the immune system is designed to adapt to a wide range of exposures, its capacity to do so depends on baseline regulatory resilience.

When immune load exceeds regulatory capacity, symptoms may emerge not because the immune system is failing, but because it is overextended.

Understanding immune health through this lens shifts the goal away from forcing immune activation and toward restoring the conditions that allow immune regulation to function effectively. (17)

The Gut–Immune Connection: Where Immune Signaling Is Shaped

A significant portion of the immune system is organized around the gastrointestinal tract. This is not incidental. The gut represents one of the body’s largest interfaces with the external environment, and immune cells positioned there are responsible for distinguishing between threats, neutral exposures, and tolerated substances.

Rather than acting solely as a digestive organ, the gut functions as a training ground for immune regulation (18).

Barrier Integrity and Immune Activation

The intestinal barrier plays a critical role in immune control. Its job is not to block all exposure, but to filter intelligently—allowing nutrients through while preventing inappropriate immune activation.

When barrier integrity is compromised, immune cells are exposed to signals they are not meant to see, innate immune activation increases, inflammatory signaling becomes persistent, and adaptive immune tolerance can erode over time.

This does not automatically result in disease, but it can shift the immune system toward heightened reactivity and reduced resilience (19).

When Immune Dysregulation Requires a Deeper Clinical Assessment

Understanding immune physiology helps explain why immune symptoms develop, but it does not always explain why they persist in a specific individual.

Immune regulation is shaped by multiple, interacting systems—including inflammatory signaling, metabolic capacity, gut integrity, nervous system tone, and environmental load. Because of this complexity, immune dysfunction is rarely driven by a single factor, and individuals with similar symptoms may require very different clinical approaches.

This is where a systems-based evaluation becomes essential.

Rather than focusing on isolated markers or single diagnoses, a functional approach to immune health evaluates patterns of regulation—including immune activation, resolution capacity, tolerance, and recovery over time (20).

In clinical practice, immune symptoms that often warrant deeper assessment include:

Recurrent or prolonged infections

Poor recovery after illness

Chronic inflammatory symptoms without a clear diagnosis

Autoimmune patterns or family history of autoimmunity

Persistent symptoms despite “normal” standard labs

In these cases, the goal is not to stimulate the immune system indiscriminately, but to identify which regulatory systems are under strain and why immune balance is failing to re-establish.

A personalized, root-cause approach allows immune support to be targeted appropriately—whether the primary driver involves inflammation, gut–immune signaling, metabolic stress, nervous system dysregulation, or cumulative environmental burden.

→ Immune Health & Autoimmune Support

Supporting Immune Health Through a Root-Cause, Systems-Based Approach

Immune symptoms are rarely isolated events. They reflect how well multiple systems in the body are communicating, adapting, and recovering over time.

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, immune health is approached through a regulatory lens, not a suppression or stimulation model. The goal is to understand why immune balance has been disrupted and which underlying systems are contributing—whether that involves inflammation, gut–immune signaling, metabolic stress, nervous system dysregulation, environmental exposure, or a combination of factors.

Care is individualized. Some patients require deeper assessment and targeted support, while others benefit from addressing foundational regulatory inputs that allow the immune system to regain balance on its own. There is no single protocol that applies universally, and immune resilience is built through context-specific care rather than one-size-fits-all solutions.

If you are experiencing frequent illness, prolonged recovery, chronic inflammation, autoimmune patterns, or immune-related symptoms that have not been explained by standard testing, support is available.

When immune symptoms persist or recovery continues to stall, early evaluation can help prevent deeper regulatory patterns from becoming entrenched.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Immune Function

What is the difference between innate and adaptive immunity?

Innate immunity is the body’s first line of defense and responds quickly and broadly to potential threats. Adaptive immunity develops over time, responds more precisely, and creates immune memory. A healthy immune system depends on proper coordination between both systems rather than dominance of one over the other.

Can you have immune problems even if your labs are normal?

Yes. Many immune issues involve regulation, signaling, or resolution rather than abnormal cell counts or antibody levels. These functional imbalances may not appear on standard blood work, especially in earlier stages of immune dysfunction.

Does a stronger immune system mean more immune activity?

No. Immune health is defined by appropriate activation and proper resolution, not constant stimulation. Excessive or prolonged immune activation can impair immune efficiency and contribute to chronic symptoms.

How does chronic inflammation affect the immune system?

When inflammation does not fully resolve, it can keep the immune system in a constant state of alert. Over time, this disrupts coordination between innate and adaptive immunity and reduces the immune system’s ability to respond efficiently.

Why do some people get sick more often than others?

Immune resilience is influenced by multiple factors, including sleep, stress, metabolic health, gut integrity, and environmental exposures. Differences in immune regulation—not just exposure to pathogens—help explain why illness frequency varies between individuals.

Can immune dysfunction develop gradually?

Yes. Immune dysfunction typically develops over time as regulatory systems are repeatedly stressed or fail to fully recover. Symptoms may appear gradually and often precede clear abnormalities on standard testing.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Nature Reviews Immunology – Regulation of immune responses: balancing activation and tolerance

Annual Review of Immunology – Immune regulation and the maintenance of self-tolerance

Nature Reviews Immunology – Innate immunity: the first line of defense against pathogens

Cell – Pattern recognition receptors and innate immune signaling pathways

Nature Immunology – Adaptive immunity and immunological memory

Immunity – Mechanisms of immune tolerance and autoimmunity

Nature Reviews Immunology – Crosstalk between innate and adaptive immune systems

Nature Reviews Immunology – Resolution of inflammation: mechanisms and therapeutic opportunities

Journal of Immunology – Chronic inflammation and persistent innate immune activation

Trends in Immunology – Dysregulation of innate–adaptive immune coordination in chronic disease

Nature Reviews Immunology – Immune exhaustion and functional impairment in chronic immune activation

Frontiers in Immunology – Functional immune assessment beyond standard laboratory testing

Nature Reviews Immunology – Systems biology approaches to immune regulation

Sleep – Sleep and circadian regulation of immune function

Journal of Applied Physiology – Exercise, immune function, and inflammation

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Stress, neuroendocrine signaling, and immune modulation

Environmental Health Perspectives – Environmental exposures and immune system regulation

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology – Gut-associated lymphoid tissue and immune education

Gut – Intestinal barrier dysfunction and immune activation

Clinical Immunology – Systems-based approaches to immune dysregulation and chronic inflammatory disease