Seed Oils and Colon Cancer: Inflammation, Omega-6 Fatty Acids, and Colorectal Cancer Risk

How industrial omega-6–rich seed oils may influence gut inflammation, microbiome balance, and long-term colorectal cancer risk

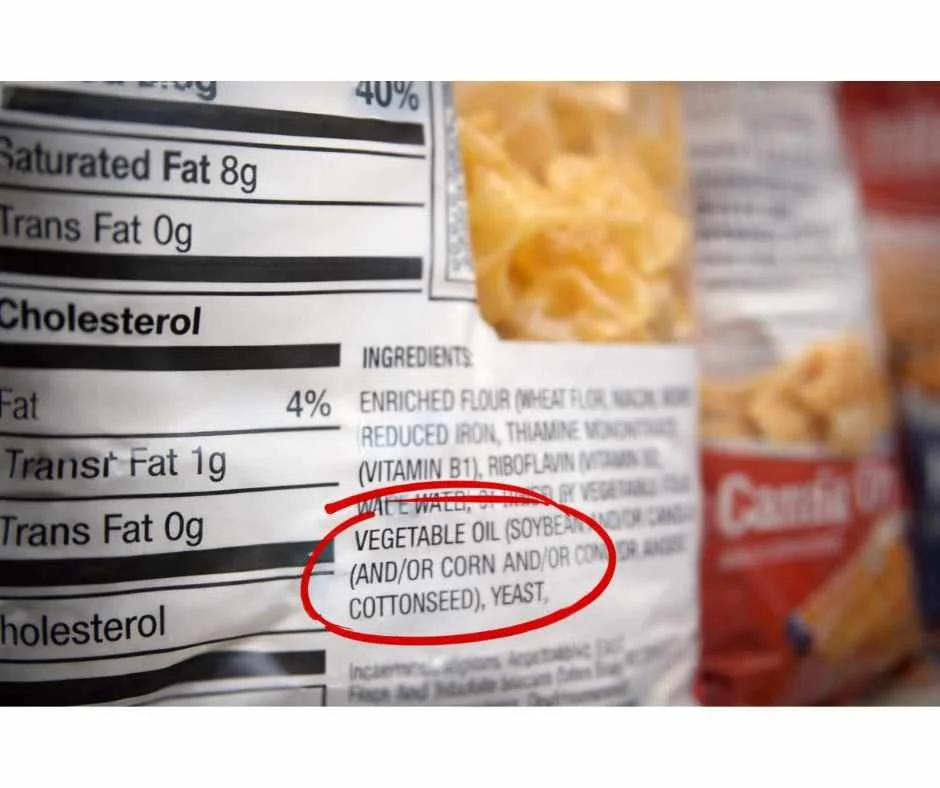

Seed oils are now a dominant fat source in the modern diet, appearing in restaurant meals, packaged foods, condiments, and many products marketed as “healthy.” While their widespread use is largely driven by cost and shelf stability, growing research has raised concerns about how frequent consumption of industrial seed oils may influence inflammation, gut health, and long-term disease risk (1).

At the same time, colorectal cancer rates are rising—particularly among younger adults. According to the American Cancer Society, colorectal cancer incidence in individuals under age 50 has increased by approximately 15% since the early 2000s (2). This troubling trend has prompted closer examination of lifestyle and dietary factors that may contribute to colon cancer risk beyond genetics alone.

Colon tissue is uniquely sensitive to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and disruptions in the gut microbiome—processes that are increasingly linked to modern dietary patterns. Emerging evidence suggests that high intake of omega-6–rich seed oils, especially within ultra-processed diets, may play a role in shaping this internal environment (3).

This article explores how seed oils may influence colon cancer risk, what the research currently shows, and how dietary choices fit into a broader, preventive approach to colorectal health.

For a broader overview of how seed oils entered the food supply, how they differ from traditional fats, and why they are so prevalent in modern diets, explore:

→ The Ugly Truth About Seed Oils and 5 Healthy Alternatives

Do Seed Oils Cause Colon Cancer?

Seed oils are not a single-cause trigger of colon cancer. Colon cancer develops through cumulative biological stress over time—driven by chronic inflammation, oxidative damage, metabolic dysfunction, microbiome disruption, and impaired cellular repair mechanisms (2,5).

That said, industrial seed oils are not metabolically neutral. Diets high in omega-6–rich seed oils—especially within ultra-processed food patterns—promote inflammatory signaling, increase susceptibility to lipid peroxidation, and alter gut microbial composition (3,5,6). These are the same biological pathways repeatedly implicated in colorectal carcinogenesis.

Colon tissue is particularly vulnerable because it is continuously exposed to dietary residues, oxidized lipids, and microbial metabolites. When dietary fat composition skews heavily toward omega-6 linoleic acid without adequate omega-3 balance, inflammatory mediators derived from arachidonic acid increase within colonic tissue (5). Over time, sustained inflammatory tone and oxidative stress create conditions that favor DNA damage, abnormal cell signaling, and tumor promotion.

Seed oils should therefore be understood as a risk-modifying exposure within modern dietary patterns. In isolation, they are not a direct carcinogen. Within ultra-processed, low-fiber, omega-6–dominant diets, they contribute to a physiological environment that supports colorectal cancer development.

The clinical issue is not a single ingredient—it is the cumulative inflammatory burden created by repeated exposure over years or decades.

Understanding how dietary fat composition interacts with inflammatory and metabolic signaling helps clarify why modern dietary patterns are under increasing scrutiny. To fully appreciate the context, it is also important to examine why colorectal cancer rates are rising—particularly in younger adults.

Why Colorectal Cancer Rates Are Rising—Especially in Younger Adults

Colorectal cancer was once considered primarily a disease of older adults, yet incidence has increased steadily among younger populations over the past two decades. This rise is particularly concerning because it is occurring in individuals without traditional risk factors such as advanced age or known hereditary syndromes (2).

Current evidence suggests that genetics alone cannot explain this trend. Instead, researchers increasingly point to modifiable lifestyle and environmental factors that influence colon physiology over time (2).

Key contributors under investigation include:

Diet quality and food processing patterns

Reduced fiber intake and altered fat composition

Metabolic dysfunction and insulin resistance

Chronic low-grade inflammation

Disruption of the gut microbiome

Modern dietary patterns differ substantially from those of previous generations. Increased reliance on ultra-processed foods, combined with changes in fat sources and cooking practices, may influence the colonic environment in ways that promote inflammation, oxidative stress, and impaired barrier integrity—factors studied in colorectal carcinogenesis (1,3).

Within this broader context, industrial seed oils have drawn attention as a frequent and often overlooked dietary exposure, particularly in diets high in processed foods.

What Are Industrial Seed Oils? Sources, Processing, and Fatty Acid Composition

Seed oils are industrial vegetable oils extracted from the seeds of plants such as soybeans, corn, canola (rapeseed), sunflower, safflower, cottonseed, rice bran, grapeseed, and peanuts. They are widely used in packaged foods and restaurant cooking due to their low cost, long shelf life, and neutral flavor.

Unlike traditional fats produced through simple mechanical methods, most seed oils undergo high-heat processing and chemical solvent extraction, followed by refining steps intended to improve appearance, odor, and stability (4).

These processing steps commonly include:

Solvent extraction to maximize oil yield

High-temperature heating to remove solvents

Refining, bleaching, and deodorizing to standardize the final product

From a nutritional perspective, seed oils are characterized by their high content of polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), particularly omega-6 linoleic acid. While omega-6 fats are essential in small amounts, modern intake levels are substantially higher than historical norms—largely due to frequent consumption of ultra-processed foods containing seed oils (3).

In the context of colon health, the concern is not the presence of fat itself, but how fatty-acid composition and processing interact with inflammatory signaling, oxidative stress, and the gut environment.

How Seed Oils May Influence Colorectal Cancer Risk: Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Microbiome Disruption

Colon cancer development is strongly influenced by the internal environment of the colon. Chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and disruption of the gut microbiome all play key roles in colorectal carcinogenesis. Research suggests that frequent intake of industrial seed oils—particularly within ultra-processed diets—may contribute to these conditions through several overlapping mechanisms (5,6).

How Omega-6 Fatty Acids Promote Chronic Inflammation in the Colon

Omega-6–rich seed oils provide linoleic acid, which can be converted into arachidonic-acid–derived signaling molecules involved in inflammatory regulation. When intake is consistently high and omega-3 intake is low, this balance may shift toward a pro-inflammatory state (5). Excess linoleic acid incorporation into cell membranes alters membrane fluidity and downstream eicosanoid signaling, amplifying pro-inflammatory prostaglandin production within colonic tissue (5).

Chronic, low-grade inflammation in the colon can:

Damage the epithelial lining

Disrupt normal cell turnover

Promote an environment that supports tumor initiation and progression

Over time, this inflammatory milieu increases vulnerability of colon tissue to malignant transformation.

Lipid Peroxidation, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage in Colonic Cells

Polyunsaturated fats are chemically unstable and more prone to oxidation, particularly when exposed to high heat during processing or cooking. Oxidized lipids and lipid peroxidation byproducts can generate reactive compounds that damage cellular structures, including DNA (6).

In the colon, oxidative stress may:

Impair DNA repair mechanisms

Increase mutation rates

Disrupt normal apoptotic signaling

These effects are widely studied in the context of cancer development and progression.

How Dietary Fat Composition Alters the Gut Microbiome

Dietary fat composition influences the structure and function of the gut microbiome. Research indicates that diets high in omega-6–rich fats can alter microbial diversity and promote bacterial profiles associated with inflammation (7,8).

Changes in the gut microbiota may contribute to colon cancer risk by:

Increasing inflammatory signaling

Producing harmful microbial metabolites

Weakening gut barrier integrity

Because the colon is directly exposed to microbial byproducts, shifts in the gut ecosystem are particularly relevant to colorectal health.

The Role of Omega-6 Linoleic Acid in Colorectal Cancer Risk

Dietary fat composition matters for colon health, not simply total fat intake. Seed oils are a concentrated source of omega-6 linoleic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid that plays a role in normal physiology but becomes problematic when intake is chronically high relative to omega-3 fats.

Historically, human diets contained a more balanced ratio of omega-6 to omega-3 fatty acids, commonly estimated between 1:1 and 4:1. Modern Western dietary patterns—largely driven by industrial seed oils—often shift this ratio to 15:1 or higher (3).

Why the Omega-6 to Omega-3 Ratio Matters for Colon Health

Omega-6 fatty acids serve as precursors for bioactive lipid mediators involved in inflammatory signaling. When omega-6 intake is excessive and omega-3 intake is low, this balance may favor signaling pathways that support chronic, low-grade inflammation (5).

In the colon, this imbalance may:

Increase inflammatory tone within colonic tissue

Alter epithelial cell turnover

Promote conditions that support tumor initiation and progression

It is important to note that linoleic acid itself is not inherently carcinogenic, and human studies do not show a simple, linear relationship between omega-6 intake and cancer risk in isolation. Instead, concern arises from dietary patterns characterized by high omega-6 exposure, low omega-3 intake, oxidative stress, and heavy reliance on ultra-processed foods (3,5).

Altered Bile Acid Metabolism and Colonic Irritation

Excess linoleic acid incorporation into colonic epithelial cell membranes alters membrane fluidity and shifts downstream eicosanoid signaling toward greater production of pro-inflammatory prostaglandins derived from arachidonic acid, reinforcing inflammatory tone within colorectal tissue (5).

Omega-6 intake within modern dietary patterns

In real-world diets, omega-6 intake rarely occurs alone. It is typically accompanied by:

Low fiber intake

Reduced antioxidant exposure

Altered gut microbiota

Increased oxidative stress

These combined factors are particularly relevant for colorectal tissue, which is directly exposed to dietary residues and microbial metabolites. Within this context, omega-6–dominant fat intake may act as a risk-modifying factor, rather than a sole cause of disease.

What the Research Says About Seed Oils and Colorectal Cancer Risk

Research examining the relationship between dietary fats and colorectal cancer includes a combination of human observational studies, experimental animal models, and mechanistic investigations. Each type of study contributes different insights—and also carries important limitations that must be acknowledged.

Human Studies on Omega-6 Intake and Colorectal Cancer

Population-based studies have explored associations between dietary fat intake and colorectal cancer risk, with particular attention to omega-6–rich fat consumption. Some observational research has reported that higher intake of omega-6 fatty acids is associated with an increased risk of colorectal cancer, especially when omega-3 intake is comparatively low (9).

These studies suggest that long-term dietary patterns—rather than short-term intake—may influence colorectal cancer risk. However, observational data cannot establish causation and may be influenced by confounding factors such as overall diet quality, fiber intake, physical activity, and metabolic health.

Animal and Mechanistic Evidence on Tumor Promotion

Experimental studies using animal models provide additional insight into biological plausibility. Diets high in omega-6 fatty acids have been shown to promote tumor development and progression in the colon under controlled conditions, particularly in the presence of inflammation or carcinogenic exposure (10).

Mechanistic research suggests that these effects may be mediated through inflammatory signaling pathways, oxidative stress, and alterations in gut microbiota composition—factors that influence colonic cell behavior and DNA integrity. While animal studies cannot be directly extrapolated to humans, they help clarify potential mechanisms that may operate within broader dietary patterns.

Limitations and Context: Why Dietary Patterns Matter

Taken together, the research does not support a simplistic conclusion that seed oils alone “cause” colon cancer. Instead, the evidence points toward a pattern-based relationship, where frequent intake of omega-6–rich seed oils within ultra-processed, low-fiber diets may contribute to an internal environment that supports colorectal carcinogenesis.

This distinction is important. Risk appears to emerge from cumulative exposure and dietary context, rather than from any single nutrient or food in isolation.

How to Reduce Colon Cancer Risk: Practical Dietary Strategies

Reducing colon cancer risk does not require extreme dietary restriction or eliminating single foods in isolation. Instead, evidence consistently points toward lowering chronic inflammatory load, improving gut health, and reducing exposure to highly processed dietary patterns over time.

Within that context, the following strategies are most relevant when considering seed oil exposure.

Reduce reliance on ultra-processed foods

For most individuals, seed oils are consumed indirectly through packaged and restaurant foods rather than as a primary cooking fat. Reducing intake of ultra-processed foods often leads to:

Lower omega-6 exposure

Higher fiber and micronutrient intake

Improved gut microbiome diversity

This shift alone can meaningfully change the internal colonic environment.

Choose more stable fats for cooking

When cooking at home, using fats that are more stable under heat may reduce the formation of oxidative byproducts. Traditional fats such as butter, ghee, tallow, or coconut oil are generally lower in polyunsaturated fat content than many seed oils and may be better suited for higher-temperature cooking (11,12).

Support omega-3 intake through whole foods

Balancing omega-6 intake with omega-3–rich foods may help modulate inflammatory signaling. Fatty fish (such as salmon, sardines, and mackerel), along with select plant sources like flaxseed and walnuts, contribute omega-3 fatty acids within whole-food dietary patterns.

Emphasize fiber and antioxidant intake

Fiber-rich foods support regular bowel movements, microbial diversity, and production of beneficial short-chain fatty acids in the colon. Antioxidant-rich fruits and vegetables may help counter oxidative stress, which is relevant to colorectal tissue integrity and DNA protection.

Taken together, these strategies aim to reduce cumulative risk factors rather than targeting any single exposure. Dietary choices function as part of a broader lifestyle pattern that influences colon health over decades.

A Functional Medicine Approach to Colon Cancer Prevention

Colon cancer risk is shaped by more than any single dietary factor. While reducing exposure to highly processed fats is a meaningful step, colorectal health is ultimately influenced by a combination of metabolic, inflammatory, digestive, and lifestyle factors that interact over time.

Key components of a comprehensive prevention-oriented approach include:

Dietary patterns rich in whole foods, particularly vegetables, fruits, and fiber-containing plants that support regular elimination and microbial diversity

Maintaining metabolic health, including blood sugar regulation and healthy body composition

Regular physical activity, which supports gut motility, immune surveillance, and insulin sensitivity

Avoidance of smoking and excessive alcohol, both of which are established colorectal cancer risk factors

Routine colorectal screening, especially for individuals with family history or additional risk factors

Chronic stress is also increasingly recognized as a contributor to inflammatory burden and digestive dysfunction. Practices that support nervous system regulation—such as mindfulness, gentle movement, adequate sleep, acupuncture, or meditation—may indirectly support colon health by reducing sustained physiological stress.

Taken together, these factors reinforce an important principle: colon cancer prevention is best approached as a long-term, systems-based process, rather than a reaction to any single exposure. Dietary choices, including fat sources, matter most when viewed within this broader physiological context.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

Taking a Proactive, Prevention-Focused Approach to Colon Health

The relationship between diet and colon cancer risk is complex and multifactorial. Seed oils do not act in isolation, but their widespread use within ultra-processed dietary patterns may contribute to chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, and gut microbiome disruption—factors that matter when evaluating long-term colorectal health.

Understanding these influences allows for more intentional choices. Reducing reliance on highly processed foods, improving dietary fat quality, supporting gut health, and addressing broader lifestyle factors can collectively shift the internal environment of the colon in a more protective direction over time.

If you have a personal or family history of colorectal cancer, ongoing digestive symptoms, inflammatory conditions, or concerns about dietary exposures, a personalized, systems-based approach is often warranted. Your colon health does not exist in isolation—it reflects interactions between nutrition, metabolism, immune function, stress physiology, and digestive integrity.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Seed Oils and Colon Cancer

How are seed oils different from other dietary factors linked to colon cancer?

Seed oils are not unique in isolation, but they are distinctive in how frequently and invisibly they appear in modern diets. Unlike whole-food fats, seed oils are consumed primarily through ultra-processed foods and restaurant meals, where they often coexist with low fiber intake, refined carbohydrates, and food additives. This combination can amplify inflammatory signaling, oxidative stress, and gut microbiome disruption—processes that are particularly relevant to colonic tissue over time.

Does eating seed oils mean you will develop colon cancer?

No. Colon cancer does not result from a single food or nutrient. It develops through a multifactorial process involving genetics, inflammation, metabolic health, gut integrity, lifestyle factors, and environmental exposures. Seed oils are best understood as a risk-modifying exposure, not a direct cause. Their impact depends on overall dietary patterns, duration of exposure, and the presence of protective factors such as fiber intake and metabolic resilience.

Why is the colon especially sensitive to dietary fat quality?

The colon is uniquely exposed to dietary residues and microbial metabolites for prolonged periods. Fat quality influences bile acid composition, microbial balance, inflammatory signaling, and epithelial repair processes. When dietary patterns promote chronic inflammation or oxidative stress, colonic cells may experience increased DNA damage, impaired repair signaling, and altered cell turnover—factors that are relevant to colorectal carcinogenesis.

Is colon cancer risk more influenced by total fat intake or fat type?

Current evidence suggests that fat type and dietary context matter more than total fat intake alone. Diets high in ultra-processed foods and omega-6–dominant fats, particularly when paired with low fiber intake, appear more concerning than fat consumption within whole-food dietary patterns. In contrast, traditional fats consumed alongside fiber-rich foods and adequate micronutrient intake may have very different physiological effects.

Can dietary changes affect colon cancer risk if you have a family history?

Dietary changes cannot eliminate inherited genetic risk or alter DNA sequence. However, nutrition can influence gene expression through epigenetic mechanisms, as well as inflammatory load, gut health, and metabolic signaling that interact with genetic susceptibility. In individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer, diet is best viewed as one component of a broader, prevention-focused strategy that also includes screening and lifestyle factors.

Why do digestive symptoms often coexist with higher colon cancer risk?

Chronic digestive symptoms can reflect underlying inflammation, microbiome imbalance, impaired barrier function, or altered motility—conditions that may also influence colorectal cancer risk over time. While digestive symptoms do not indicate cancer, they can signal physiological stress within the gut environment. Addressing dietary patterns that promote inflammation or microbiome disruption may support overall digestive resilience.

Should people with inflammatory bowel conditions be more cautious about seed oils?

Individuals with inflammatory bowel conditions often have heightened sensitivity to dietary factors that influence inflammation and oxidative stress. Diets high in ultra-processed foods—including common sources of seed oils—may exacerbate inflammatory burden in susceptible individuals. In these cases, reducing processed food intake and focusing on whole-food dietary patterns may support gut stability as part of a comprehensive care plan.

Do dietary changes replace the need for colon cancer screening?

No. Dietary and lifestyle strategies support long-term health but do not replace recommended colorectal screening. Screening remains one of the most effective tools for early detection and prevention and should always be followed according to medical guidelines, especially for individuals with additional risk factors.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

American Cancer Society – Colorectal Cancer Facts & Figures: Trends in Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer

Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention – Rising Incidence of Early-Onset Colorectal Cancer and Lifestyle Associations

Nutrition Reviews – The Importance of the Omega-6 to Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio in Health and Disease

European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology – Industrial Processing of Vegetable Oils and Effects on Oxidative Stability

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases – Chronic Inflammation as a Driver of Colorectal Carcinogenesis

Free Radical Biology & Medicine – Lipid Peroxidation, Oxidative Stress, and DNA Damage in Cancer Development

Gut – Dietary Fat, Gut Microbiota, and Colorectal Cancer Risk

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology – The Gut Microbiome and Colorectal Cancer Progression

Cancer Causes & Control – Omega-6 Fatty Acid Intake and Risk of Colorectal Cancer

Carcinogenesis – High Omega-6 Diets and Tumor Promotion in Experimental Models

Journal of the American Oil Chemists’ Society – Thermal Stability of Dietary Fats and Formation of Oxidative Byproducts

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition – Dietary Patterns, Fiber Intake, and Colorectal Cancer Prevention