Autoimmune Disease: A Functional Medicine Approach to Improving Symptoms and Immune Regulation

Why gut health, environmental exposures, metabolic stress, and immune signaling—not symptom suppression—shape autoimmune outcomes

Autoimmune diseases are increasing at a pace that can no longer be explained by genetics alone. Conditions such as Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, multiple sclerosis, inflammatory bowel disease, psoriasis, and type 1 diabetes now affect millions of people worldwide, often beginning years before a clear diagnosis is made. For many individuals, symptoms quietly accumulate—fatigue, pain, brain fog, digestive issues, rashes, or hormonal disruption—long before conventional testing provides answers.

Conventional care typically focuses on suppressing immune activity once autoimmunity is established. While this approach can reduce symptom severity, it often does little to address why immune regulation became disrupted in the first place. As a result, many people continue to experience fluctuating symptoms, additional diagnoses, or a gradual loss of quality of life despite ongoing treatment.

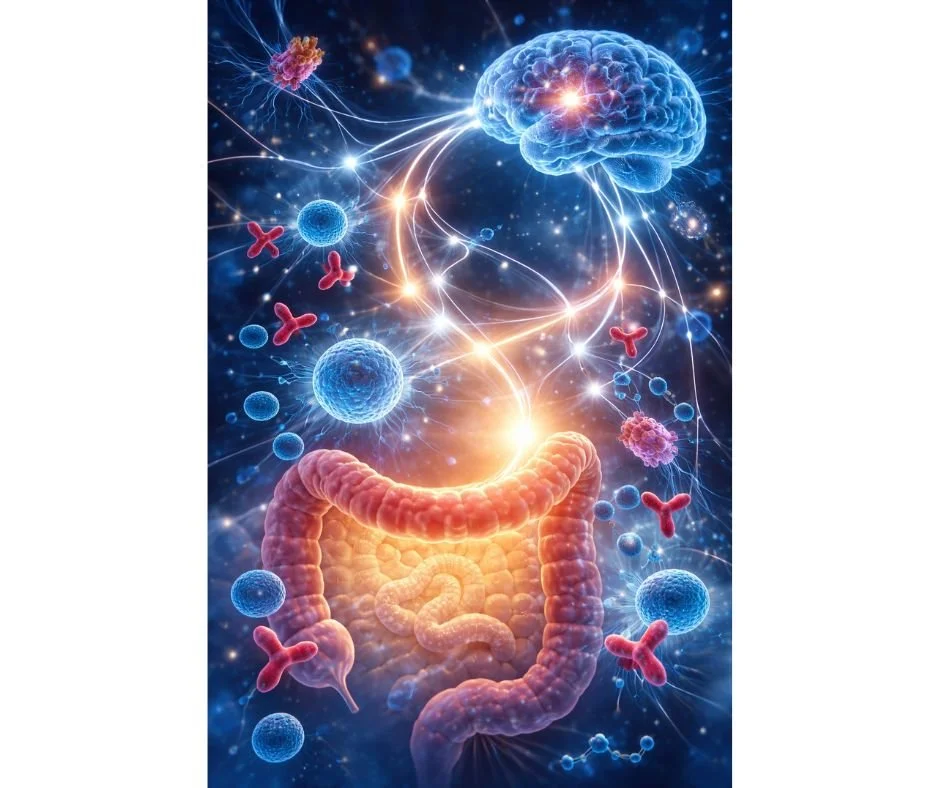

From a functional medicine perspective, autoimmune disease is not viewed as a single isolated diagnosis or an immune system that has “turned against itself” without reason. Instead, it reflects a breakdown in immune tolerance driven by a combination of genetic susceptibility, environmental exposures, gut barrier dysfunction, metabolic stress, and nervous system imbalance. Understanding these upstream factors allows care to shift from symptom management toward immune regulation, resilience, and long-term stability.

This article explores what autoimmunity truly means at a systems level, why certain individuals are more vulnerable, and how a functional medicine approach can support improved symptoms, immune balance, and overall health.

Autoimmune Disease Is Rising—And Symptom Management Alone Is Not Enough

The Growing Prevalence of Autoimmune Disease

Autoimmune diseases are now recognized as one of the fastest-growing categories of chronic illness worldwide, with prevalence increasing steadily over the past several decades (1). More than 100 distinct autoimmune conditions have been identified, affecting nearly every organ system in the body, and many individuals carry more than one diagnosis over their lifetime (2).

Why Genetics Alone Cannot Explain the Increase

This rise cannot be explained by genetics alone. Human genetics have not changed meaningfully in such a short time frame. What has changed is the environment in which the immune system develops and operates—dietary patterns, chemical exposures, microbial diversity, stress physiology, sleep disruption, medication use, and overall metabolic load (3,4).

The Limitations of a Symptom-Suppression Model

Despite this complexity, conventional autoimmune care is largely structured around symptom control. Immunosuppressive medications, biologics, and anti-inflammatory drugs are commonly used to reduce immune activity once tissue damage or overt inflammation is present. While these interventions may be necessary and beneficial in certain stages of disease, they are not designed to restore immune tolerance or address upstream drivers that initiated immune dysregulation (5).

As a result, many individuals experience partial relief without true stability. Symptoms may fluctuate, new autoimmune diagnoses may emerge, medication requirements may increase, or side effects may accumulate over time (6).

A Systems-Based Perspective on Immune Regulation

A functional medicine approach asks a different question: not only how to reduce symptoms, but why immune regulation was lost in the first place. By examining immune signaling within the broader context of gut integrity, antigen exposure, metabolic stress, hormonal influences, and nervous system regulation, autoimmune disease can be addressed as a systems-level imbalance rather than an isolated immune defect (7).

This distinction is critical. Managing inflammation alone does not necessarily restore immune balance. Supporting immune regulation requires understanding the terrain in which the immune system is operating—and intervening at the level where dysregulation began.

What Autoimmunity Really Means at the Immune-System Level

Immune Tolerance vs Immune Suppression

In a healthy immune system, tolerance allows immune cells to distinguish between true threats—such as viruses, bacteria, and abnormal cells—and the body’s own tissues. This process is tightly regulated through multiple checkpoints involving innate immunity, adaptive immunity, regulatory T cells, and signaling molecules that determine when inflammation should be activated and when it should resolve (8).

Autoimmune disease does not simply reflect an “overactive” immune system. Rather, it represents a loss of immune tolerance, in which regulatory mechanisms fail to properly restrain immune responses against self tissue (9). Suppressing immune activity may reduce inflammation temporarily, but it does not inherently restore the mechanisms responsible for tolerance.

This distinction is central to understanding why autoimmune symptoms often return, shift, or progress over time despite aggressive treatment.

Why the Immune System Begins Attacking Self Tissue

Immune dysregulation develops when the signals that guide immune recognition become distorted. This can occur through repeated or chronic exposure to inflammatory stimuli, molecular mimicry between pathogens and host tissue, persistent antigen exposure from the gut, or impaired clearance of immune complexes (10,11).

Over time, these disruptions can alter how immune cells are trained, activated, and regulated. Antigen-presenting cells may become overly stimulatory, regulatory pathways may weaken, and inflammatory cytokines may remain elevated beyond their appropriate window (12).

Rather than a sudden failure, autoimmunity typically develops gradually. Subclinical immune activation may be present for years before symptoms become severe enough to meet diagnostic criteria, which helps explain why early autoimmune disease is often missed or dismissed (13).

Autoimmune Disease as a Systems-Level Breakdown

Because immune regulation depends on multiple interconnected systems, autoimmune disease rarely exists in isolation. Gut integrity, metabolic health, detoxification capacity, hormonal signaling, and nervous system regulation all influence immune behavior (14,15).

When these systems are under chronic stress, the immune system adapts in ways that may initially be protective but eventually become maladaptive. This is why autoimmune conditions often cluster, why symptoms evolve over time, and why focusing on a single organ or antibody marker rarely captures the full picture (16).

From a functional medicine perspective, autoimmunity is best understood not as a defect in one immune pathway, but as a reflection of cumulative system strain. Restoring balance requires identifying where immune regulation has been disrupted—and which underlying systems are contributing to that disruption.

Types of Autoimmune Disease and Who They Impact

Organ-Specific Autoimmune Conditions

Organ-specific autoimmune diseases primarily target a single tissue or gland. In these conditions, immune activity is directed toward antigens unique to a particular organ, leading to localized dysfunction. Common examples include Hashimoto’s thyroiditis and Graves’ disease affecting the thyroid, type 1 diabetes affecting the pancreas, and Addison’s disease affecting the adrenal glands (17).

Although damage may appear confined to one organ, systemic immune dysregulation is still present. Fatigue, inflammation, metabolic disruption, and secondary hormonal effects are common, even when laboratory findings suggest organ-specific involvement alone.

Systemic (Non–Organ-Specific) Autoimmune Conditions

Systemic autoimmune diseases involve widespread immune activation and inflammation across multiple tissues. Conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, and mixed connective tissue disease affect joints, skin, blood vessels, kidneys, and other organs simultaneously (18).

Because multiple systems are involved, symptoms are often diffuse and fluctuating. Pain, fatigue, rashes, neurological symptoms, and digestive disturbances may coexist, making diagnosis and management more complex. These conditions also carry a higher likelihood of overlapping autoimmune diagnoses over time.

Why Women Are Disproportionately Affected

Approximately 75–80% of autoimmune disease cases occur in women, a pattern observed across nearly all major autoimmune conditions (19). While the exact mechanisms are still being studied, differences in sex hormones, immune signaling, and X-chromosome–linked immune genes appear to influence susceptibility.

Estrogen plays a complex role in immune activation, sometimes enhancing immune responsiveness while also increasing the risk of immune dysregulation under chronic stress or inflammatory conditions. This helps explain why many autoimmune diseases emerge or worsen during periods of hormonal transition.

Hormonal Transitions and Immune Vulnerability

Autoimmune disease onset or symptom flares commonly occur during pregnancy, postpartum recovery, perimenopause, and menopause—times marked by rapid hormonal shifts and increased metabolic demand (20). These transitions can alter immune tolerance, gut permeability, and stress physiology, increasing vulnerability in individuals with underlying genetic or environmental risk factors.

This pattern reinforces the importance of viewing autoimmune disease through a whole-body lens rather than as an isolated immune malfunction.

Why Genetics Load the Gun—But Environment Pulls the Trigger

Genetic Predisposition and Familial Autoimmune Patterns

Genetic susceptibility plays an important role in autoimmune disease risk. Certain gene variants involved in immune recognition, antigen presentation, and inflammatory signaling increase vulnerability to immune dysregulation (21). Autoimmune diseases also tend to cluster within families, though the specific diagnosis may differ from one individual to another.

For example, one family member may develop rheumatoid arthritis while another develops Hashimoto’s thyroiditis or lupus. This pattern suggests that shared genetic tendencies toward immune imbalance exist, even when the clinical expression varies (22). Genetics, however, do not determine destiny. Many individuals with autoimmune-associated genes never develop disease.

Environmental Triggers That Disrupt Immune Balance

Environmental exposures are now recognized as critical drivers that influence whether genetic risk translates into active disease. Factors such as mold and mycotoxins, heavy metals, chronic infections, medications, chemical exposures, smoking, poor sleep, and prolonged psychological stress have all been associated with immune dysregulation and increased autoimmune risk (23,24).

These exposures can alter immune signaling directly or indirectly by increasing inflammatory burden, impairing detoxification pathways, disrupting mitochondrial function, and weakening regulatory immune mechanisms. Repeated or cumulative exposure appears to be more significant than any single event.

Epigenetics and Immune Expression

Epigenetics describes how environmental inputs influence gene expression without altering DNA structure. Nutrition, toxin exposure, stress physiology, sleep quality, and microbial diversity all shape how immune-related genes are expressed over time (25).

This helps explain why autoimmune disease may develop years after exposure, why symptoms fluctuate, and why disease progression differs widely between individuals with similar diagnoses. From a functional medicine perspective, epigenetic influence represents opportunity—modifiable factors that can be addressed to support immune regulation and resilience.

The Gut–Immune Connection in Autoimmune Disease

Intestinal Permeability and Antigen Load

The gastrointestinal tract is one of the largest immune interfaces in the body. A healthy gut lining acts as a selective barrier—allowing nutrients to pass through while preventing bacteria, toxins, and undigested food particles from entering systemic circulation. When this barrier becomes compromised, immune exposure increases (26).

Intestinal permeability, often referred to as “leaky gut,” allows antigens that would normally remain contained within the gut lumen to cross into the bloodstream. This increased antigen load places constant demand on the immune system, increasing the likelihood of inappropriate immune activation, particularly in genetically susceptible individuals (27).

Over time, repeated immune stimulation from gut-derived antigens can contribute to loss of immune tolerance and sustained inflammatory signaling, a mechanism increasingly implicated in autoimmune disease development and progression (28).

Microbiome Disruption and Immune Signaling

The gut microbiome plays a central role in immune education and regulation. Commensal bacteria influence regulatory T-cell development, cytokine balance, and immune tolerance through direct cell signaling and microbial metabolite production (29).

Disruptions to microbial diversity—whether from antibiotics, infections, inflammatory diets, chronic stress, or environmental exposures—can shift immune signaling toward a more pro-inflammatory, reactive state. These changes may persist long after the original trigger has resolved, contributing to ongoing immune dysregulation (30).

Why “Leaky Gut” Is a Pathway, Not a Diagnosis

Intestinal permeability is not a disease itself, nor is it a standalone explanation for autoimmune illness. It is a mechanism—a pathway through which environmental exposures, dietary antigens, and microbial byproducts interact with the immune system.

In functional medicine, addressing gut integrity is not about labeling or blame. It is about reducing immune burden, restoring barrier function, and improving immune communication. For many individuals with autoimmune disease, improving gut health becomes a foundational step toward stabilizing symptoms and supporting long-term immune regulation.

Common Symptoms Across Autoimmune Conditions

Systemic Symptoms Beyond the Primary Diagnosis

Although autoimmune diseases are often named for the organ or tissue they affect, symptoms are rarely limited to that single system. Many individuals experience widespread effects that reflect global immune activation, inflammatory signaling, and metabolic stress rather than localized tissue damage alone (31).

Common systemic symptoms include persistent fatigue, diffuse pain, joint stiffness, muscle weakness, headaches, rashes, digestive disturbances, and changes in mood or cognitive clarity. These symptoms frequently precede diagnosis and may persist even when disease-specific markers appear controlled (32).

Because these symptoms overlap with many other chronic conditions, they are often minimized or attributed to stress, aging, or lifestyle factors rather than recognized as manifestations of immune dysregulation.

Why Symptoms Fluctuate and Cluster Over Time

Autoimmune symptoms commonly follow a relapsing–remitting pattern. Periods of relative stability may be interrupted by flares triggered by infection, psychological stress, hormonal shifts, dietary changes, sleep disruption, or environmental exposures (33).

Over time, additional systems may become involved. Digestive symptoms may precede joint pain. Thyroid dysfunction may follow years of fatigue or mood changes. This clustering reflects shared inflammatory and regulatory pathways rather than the emergence of unrelated diseases (34).

From a functional medicine perspective, symptom patterns are not random. They provide insight into immune burden, regulatory capacity, and system resilience—and help guide prioritization of intervention.

Why Conventional Treatment Often Falls Short

Symptom Suppression vs Immune Regulation

Conventional autoimmune treatment is largely designed to reduce inflammation or suppress immune activity once disease is established. Medications such as corticosteroids, disease-modifying agents, and biologics can be effective for controlling acute symptoms and preventing tissue damage in certain cases.

However, suppressing immune activity does not necessarily restore immune balance. These therapies do not address why immune tolerance was lost or why inflammatory signaling became persistent. As a result, symptom control often depends on ongoing medication use, and flares may recur when treatment is reduced or interrupted.

From a systems-based perspective, inflammation is a signal rather than the root problem. Without addressing the conditions driving immune dysregulation, suppression alone may provide relief without stability.

Why Labs Can Look “Normal” Despite Ongoing Symptoms

Standard laboratory testing is designed to detect disease at a structural or diagnostic level, not early immune dysfunction. Autoimmune processes can be active long before antibody markers rise or organ damage becomes measurable.

Immune signaling, mitochondrial stress, gut barrier disruption, and nervous system imbalance do not always appear on routine panels. This disconnect can leave individuals feeling dismissed or confused when symptoms persist despite “normal” results.

Functional medicine evaluates immune health through a broader lens—considering patterns over time, symptom clusters, environmental exposures, and functional markers that reflect system stress rather than disease end points. This approach helps explain why individuals may feel unwell long before a formal autoimmune diagnosis is made.

How Functional Medicine Approaches Autoimmune Disease Differently

Identifying Root Causes Instead of Isolated Diagnoses

Functional medicine does not begin with the autoimmune label alone. It starts by asking what underlying factors are influencing immune behavior and why regulation has been lost. Rather than viewing each diagnosis as a separate condition, autoimmune disease is understood as the downstream expression of cumulative system stress.

This approach looks for patterns across immune activation, gut integrity, metabolic function, detoxification capacity, hormonal signaling, and nervous system regulation. Symptoms are not treated as unrelated problems to suppress, but as meaningful signals that help identify where imbalance exists.

By addressing contributors such as chronic immune triggers, inflammatory load, nutrient depletion, impaired barrier function, and autonomic dysregulation, care shifts from managing flare cycles to supporting long-term immune stability.

Personalized Care Based on Immune, Gut, and Metabolic Terrain

No two individuals experience autoimmune disease in the same way. Genetics, life stage, environmental exposures, stress patterns, infections, and prior medical interventions all shape immune behavior differently. For this reason, a standardized protocol is rarely effective.

Functional medicine emphasizes individualized assessment and targeted intervention. Treatment plans are adjusted over time based on how the body responds, with the goal of improving resilience rather than forcing suppression. This allows care to evolve as immune regulation improves.

Individuals seeking this type of comprehensive, systems-based care may benefit from programs focused on immune regulation, inflammation reduction, and root-cause evaluation.

→ Immune Health & Autoimmune Support

Core Therapeutic Foundations in Functional Autoimmune Care

Nutrition, Inflammatory Load, and Immune Balance

Dietary inputs strongly influence immune signaling, gut integrity, and inflammatory tone. In autoimmune disease, repeated exposure to inflammatory foods, unstable blood sugar, and inadequate nutrient intake can perpetuate immune activation even in the absence of obvious triggers.

A functional approach prioritizes reducing immune burden while supporting nutrient sufficiency. This may include removing highly inflammatory inputs, improving food quality, and tailoring dietary strategies based on digestive capacity, metabolic needs, and symptom response rather than rigid rules.

The goal is not dietary perfection, but creating an internal environment that supports immune regulation instead of constant activation.

Targeted Supplementation and Nutrient Repletion

Autoimmune disease is frequently associated with increased nutrient demand. Chronic inflammation, impaired absorption, medication use, and stress physiology can all contribute to depletion of nutrients involved in immune modulation, mitochondrial function, and tissue repair.

Targeted supplementation is used strategically—not as a blanket approach, but to address identified needs and support specific physiological pathways. When used appropriately, nutritional and botanical support can help reduce inflammatory signaling, support gut integrity, and improve immune resilience.

Functional Lab Testing to Identify Drivers

Because autoimmune disease reflects system-level imbalance, testing is often used to identify contributing factors that do not appear on standard panels. Functional assessment may include markers of gut function, immune activation, nutrient status, metabolic stress, and toxic burden.

This information helps prioritize interventions and avoid guesswork, allowing care to focus on the most relevant drivers rather than treating symptoms in isolation.

Herbal Medicine and Immune Modulation

Herbal medicine is used to support immune regulation, inflammatory balance, and stress adaptation. When selected appropriately, botanical therapies can modulate immune activity without the blunt effects of suppression, supporting balance rather than forcing shutdown.

Herbal strategies are individualized based on constitution, symptom patterns, and concurrent therapies, and are often integrated with nutrition and lifestyle support for greater effect.

Acupuncture and Nervous System Regulation

The nervous system plays a critical role in immune regulation. Chronic stress, autonomic imbalance, and impaired parasympathetic activity can amplify inflammatory signaling and reduce immune tolerance.

Acupuncture supports immune health by calming stress physiology, improving circulation, regulating autonomic function, and supporting the body’s innate capacity to restore balance. For many individuals with autoimmune disease, nervous system regulation becomes a key component of symptom stabilization and recovery.

A Systems-Based Approach to Autoimmune Care in Denver

Autoimmune disease does not develop in isolation, and it rarely improves through isolated interventions. Effective care requires understanding how immune regulation is shaped by the interaction between gut health, metabolic function, hormonal signaling, environmental exposures, and nervous system balance over time.

At Denver Sports and Holistic Medicine, autoimmune care is approached through a systems-based framework that prioritizes identifying and addressing the underlying drivers influencing immune behavior. Rather than focusing solely on suppressing symptoms or targeting a single organ, care is structured to support immune regulation, resilience, and long-term stability across interconnected systems.

This process begins with a comprehensive clinical assessment that considers medical history, symptom patterns, prior treatments, environmental exposures, diet, stress physiology, and lifestyle factors. These inputs help determine where immune burden is originating and which systems require the most immediate support.

Treatment plans are individualized and adjusted over time based on response, capacity, and life stage. The goal is not to override the immune system, but to remove obstacles to regulation and support the body’s inherent ability to restore balance when conditions allow.

Individuals seeking this type of integrative, root-cause care may benefit from working within a functional medicine model that emphasizes systems thinking, personalization, and long-term immune health.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

Next Steps for Autoimmune Disease Care

Autoimmune disease does not follow a single, fixed trajectory. When immune dysregulation is identified early and addressed appropriately, symptoms can stabilize, improve, and in some cases enter remission. Persistent or worsening symptoms often reflect unresolved drivers rather than an irreversible condition.

A functional medicine approach focuses on understanding how genetics, environment, gut health, metabolism, hormones, and nervous system regulation interact to influence immune behavior over time. By identifying and addressing these upstream factors, care can move beyond symptom suppression toward supporting immune regulation, resilience, and long-term stability.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Autoimmune Disease

Can autoimmune disease go into remission?

Yes. Many autoimmune conditions can improve significantly or enter remission when immune dysregulation is identified early and underlying drivers are addressed. Outcomes depend on the type of condition, duration of symptoms, overall health, and how comprehensively contributing factors are evaluated and supported.

Why do autoimmune symptoms come and go?

Autoimmune symptoms often fluctuate because immune regulation is influenced by multiple factors, including stress, infections, sleep quality, hormonal shifts, diet, and environmental exposures. When immune burden increases or regulatory capacity is exceeded, symptoms may flare. When stressors are reduced, symptoms may improve.

Can gut health really affect autoimmune disease?

Yes. The gut plays a central role in immune regulation. Changes in gut barrier integrity, microbiome balance, and immune signaling within the digestive tract can influence systemic inflammation and immune tolerance, which may affect autoimmune symptoms.

Why are autoimmune diseases more common in women?

Autoimmune diseases occur more frequently in women due to differences in immune signaling, hormonal influences, and genetic factors. Hormonal transitions such as pregnancy, postpartum recovery, and menopause can affect immune balance and symptom expression.

Can stress make autoimmune disease worse?

Chronic stress can significantly influence immune regulation. Prolonged stress affects nervous system balance, inflammatory signaling, gut function, and hormone regulation, all of which can contribute to symptom flares or delayed recovery.

Why do my labs look normal if I still have symptoms?

Standard lab tests are designed to detect established disease, not early or functional immune dysregulation. Immune signaling imbalances, metabolic stress, and nervous system factors may contribute to symptoms long before conventional markers become abnormal.

Is autoimmune disease genetic?

Genetics can increase susceptibility, but they do not determine outcomes on their own. Environmental exposures, lifestyle factors, infections, and stress all influence whether genetic risk translates into active disease.

Can autoimmune disease be addressed without suppressing the immune system?

In some cases, yes. A systems-based approach focuses on supporting immune regulation rather than simply suppressing immune activity. The appropriate strategy depends on the condition, symptom severity, and overall health context.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

The Lancet – Global prevalence and rising burden of autoimmune disease

Nature Reviews Immunology – The expanding spectrum of autoimmune disorders

Environmental Health Perspectives – Environmental contributors to immune dysregulation

Annual Review of Immunology – Immune system development and environmental influence

Journal of Autoimmunity – Limitations of immunosuppressive therapy in autoimmune disease

Clinical Immunology – Long-term outcomes and disease progression in autoimmunity

Frontiers in Immunology – Systems biology approaches to immune regulation

Nature Immunology – Mechanisms of immune tolerance and self-recognition

Immunity – Regulatory T cells and loss of immune tolerance

Trends in Immunology – Molecular mimicry and autoimmune disease development

Journal of Experimental Medicine – Antigen presentation and chronic immune activation

Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews – Cytokine imbalance in autoimmune disease

Autoimmunity Reviews – Preclinical immune activation and delayed diagnosis

Cell Metabolism – Metabolic regulation of immune function

Endocrine Reviews – Hormonal modulation of immune signaling

Nature Reviews Endocrinology – Systems interactions in autoimmune disease

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Organ-specific autoimmune disorders

Rheumatology – Systemic autoimmune disease mechanisms

Nature Reviews Rheumatology – Sex differences in autoimmune disease prevalence

Menopause – Hormonal transitions and immune vulnerability

Human Molecular Genetics – Genetic susceptibility loci in autoimmune disease

Arthritis & Rheumatology – Familial clustering of autoimmune disorders

Toxicological Sciences – Environmental toxins and immune dysregulation

Journal of Internal Medicine – Infection, stress, and autoimmune disease risk

Epigenetics – Environmental regulation of immune gene expression

Gut – Intestinal barrier function and immune activation

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology – Intestinal permeability and systemic inflammation

Clinical Reviews in Allergy & Immunology – Gut-derived antigens and autoimmunity

Nature Reviews Immunology – Microbiome regulation of immune tolerance

Frontiers in Microbiology – Dysbiosis and inflammatory immune signaling

Autoimmune Diseases – Systemic symptom patterns in autoimmune conditions

BMC Medicine – Symptom burden prior to autoimmune diagnosis

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity – Stress, immune flares, and symptom variability

Journal of Translational Medicine – Shared inflammatory pathways across autoimmune diseases