The Low FODMAP Diet for IBS, SIBO, and Chronic Digestive Symptoms

A functional-medicine approach to reducing bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and bowel irregularity

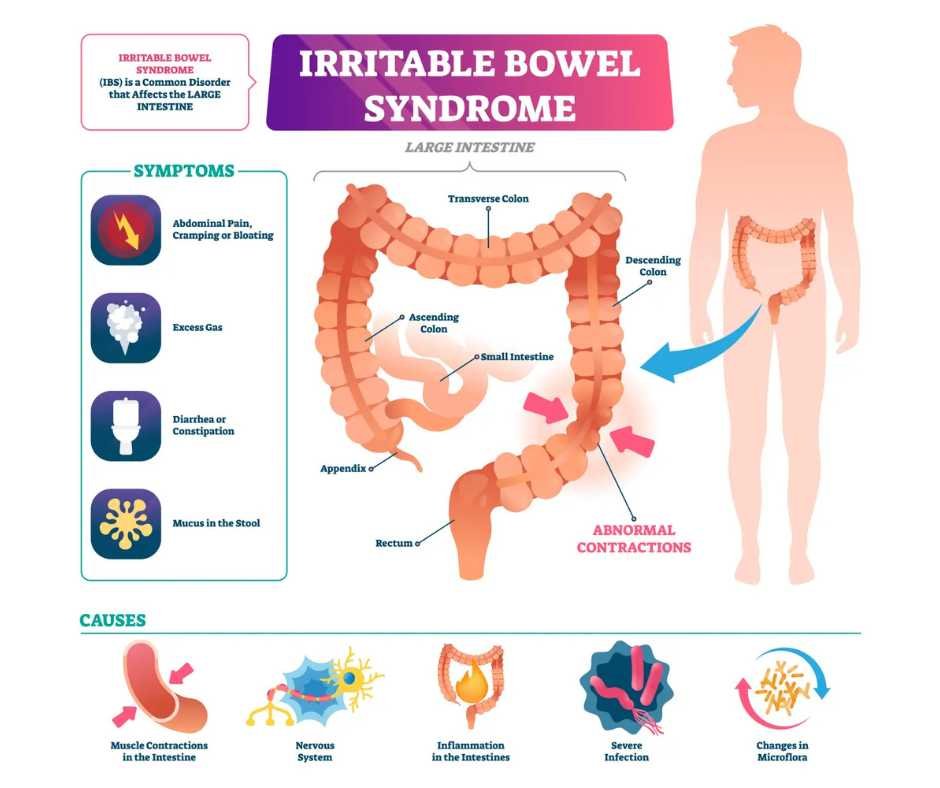

Bloating after meals. Abdominal pain that flares unpredictably. Constipation and diarrhea that alternate without a clear pattern.

If these digestive symptoms sound familiar, you are not alone—and they are rarely “just stress” or something you simply have to tolerate.

For many individuals with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), or chronic functional digestive disorders, symptoms are driven by how specific carbohydrates interact with gut bacteria, intestinal motility, and visceral sensitivity.

The low FODMAP diet is a clinically validated, short-term elimination diet designed to reduce bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and bowel irregularity by limiting fermentable carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. When applied strategically—and individualized rather than followed indefinitely—it can be an effective therapeutic tool for symptom relief while deeper contributors to gut dysfunction are identified and addressed.

This article discusses how the low FODMAP diet works, which digestive conditions may benefit most, what the research shows, and why dietary restriction alone is not a long-term solution without addressing underlying gut dysfunction.

What Is the Low FODMAP Diet?

How fermentable carbohydrates trigger bloating, gas, and abdominal pain

FODMAP is an acronym that describes specific types of carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine:

Fermentable

Oligosaccharides

Disaccharides

Monosaccharides

Polyols

These carbohydrates consist of bonded sugar molecules. Because the small intestine is optimized to absorb single sugar units, FODMAPs are only partially absorbed and instead pass into the large intestine. There, they draw water into the bowel and are rapidly fermented by gut bacteria, producing gas and short-chain fatty acids. In susceptible individuals, this process leads to bloating, abdominal distention, pressure, and pain (1).

Importantly, this mechanism does not cause symptoms in everyone. Problems arise when fermentable carbohydrates interact with underlying vulnerabilities such as altered gut motility, dysbiosis, visceral hypersensitivity, impaired digestion, or bacterial overgrowth. In these contexts, normal fermentation becomes excessive and symptomatic rather than benign.

When food reactions are persistent, unpredictable, or worsening, they often reflect deeper microbiome imbalance or gut dysfunction—not a simple intolerance. In these cases, dietary restriction alone is rarely sufficient without targeted evaluation and treatment.

The low FODMAP diet is a symptom-management strategy—it does not treat the underlying causes of IBS, SIBO, celiac disease, or inflammatory bowel disease.

Who May Benefit From a Low FODMAP Diet

Digestive symptoms linked to carbohydrate malabsorption

A low FODMAP approach may be appropriate for individuals who experience recurrent or unexplained digestive symptoms, including:

Chronic bloating or excessive gas

Abdominal pain, pressure, or cramping

Diarrhea, constipation, or alternating bowel patterns

Visible abdominal distention, particularly after meals

These symptom patterns are commonly observed in conditions such as:

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS)

Small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO)

Celiac disease with persistent IBS-like symptoms despite strict gluten avoidance

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), particularly when functional symptoms persist during remission

Leaky gut and post-infectious gut dysfunction

In IBS and SIBO, intestinal motility is often impaired, allowing fermentable carbohydrates to remain in the gut longer. This prolonged exposure increases bacterial fermentation, gas production, and symptom flares (2)(3).

When the intestinal barrier is compromised, food reactions tend to intensify, making gut repair and microbiome regulation as important as dietary modification when applying a low FODMAP strategy.

Does the Low FODMAP Diet Help IBS and IBD?

Evidence for the low FODMAP diet in IBS and IBD

The strongest and most consistent evidence for the low FODMAP diet exists in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Multiple randomized and controlled studies demonstrate meaningful reductions in bloating, abdominal pain, gas, and overall symptom severity when high-FODMAP foods are reduced (4)(5).

Because of these outcomes, researchers have also examined the role of a low FODMAP diet in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Current evidence indicates that while the diet does not reduce intestinal inflammation or alter disease activity, it may improve functional symptoms such as bloating, gas, abdominal pain, and fatigue in some individuals (6).

In one analysis of nine studies involving patients with IBD, improvements were observed in functional gastrointestinal symptoms, while inflammatory markers and objective disease measures remained unchanged (7). A smaller pediatric study similarly reported symptom reduction in most children following a low FODMAP intervention (8).

Because research in IBD populations is still evolving—and because unnecessary restriction carries nutritional risk—professional guidance is essential when applying a low FODMAP diet in the context of inflammatory bowel disease.

→ Gut Health & Digestive Restoration

The Low FODMAP Diet and Celiac Disease

Why digestive symptoms persist in celiac disease despite a gluten-free diet

People with celiac disease must remove gluten from their diet completely. However, some continue to experience persistent IBS-like symptoms even with strict adherence.

A review of studies examining low FODMAP interventions in celiac patients showed improvements in digestive symptoms, quality of life, and overall well-being (9). While these findings are promising, they also highlight the importance of avoiding unnecessary long-term restriction.

High vs. Low FODMAP Foods

Foods more likely to trigger bloating, gas, and abdominal discomfort

Many nutrient-dense, whole foods naturally contain FODMAPs. Symptoms are not caused by food quality, but by carbohydrate structure, portion size, gut motility, and microbial fermentation. Common high-FODMAP categories include certain fruits, dairy products, grains, and legumes.

Higher FODMAP foods commonly associated with symptoms:

Alcohol and high-caffeine beverages

Cashews and pistachios

Watermelon, apricots, cherries, and other stone fruits

High-fructose corn syrup and certain sweeteners

Onions, artichokes, beets, and some cruciferous vegetables

Regular milk, yogurt, ice cream, and some soft cheeses

Wheat- and rye-based products

Lower FODMAP alternatives that are often better tolerated

These foods are typically absorbed more efficiently in the small intestine and are less likely to fuel excessive fermentation when consumed in appropriate portions:

Pineapple, kiwi, and oranges

Maple syrup and small amounts of dark chocolate

Carrots, potatoes, and eggplant

Lactose-free dairy, almond milk, brie, and most hard cheeses

Oats, quinoa, rice, and gluten-free breads

Eggs, tofu, and minimally processed meats and seafood

Important: The goal of a low FODMAP diet is not permanent avoidance. Many people are able to tolerate a wide range of higher-FODMAP foods once gut motility, microbiome balance, and intestinal barrier function are restored. Long-term restriction without reintroduction is neither necessary nor advisable.

Why the Low FODMAP Diet Is Not Meant to Be Long Term

Protecting nutrient adequacy and gut microbiome diversity

While the low FODMAP diet can be highly effective for short-term symptom relief, strict long-term restriction is not recommended. Prolonged avoidance of fermentable carbohydrates has been associated with nutrient inadequacies and reductions in gut microbiome diversity, both of which can impair digestive resilience over time (10).

Research consistently shows better symptom outcomes, nutritional status, and dietary expansion when the low FODMAP diet is implemented with professional guidance, particularly during the critical reintroduction phase (11). Without this step, individuals may unnecessarily eliminate well-tolerated foods, prolong restriction, and miss underlying contributors to digestive dysfunction.

For this reason, a low FODMAP approach is most effective when used as part of a broader gut-healing strategy that prioritizes motility, microbial balance, and intestinal barrier repair—not dietary avoidance alone.

How the Low FODMAP Diet Works: The Three Clinical Phases

The three clinical phases of a low FODMAP diet

The low FODMAP diet is not a single-phase elimination plan. It is a stepwise process designed to reduce symptoms temporarily while identifying individual tolerance patterns and supporting long-term dietary flexibility.

Elimination phase

This initial phase typically lasts two to six weeks and involves removing high-FODMAP foods to reduce carbohydrate fermentation, gas production, and symptom severity. The goal is symptom stabilization—not nutritional perfection or prolonged restriction.

Reintroduction phase

Over six to eight weeks, FODMAP-containing foods are systematically reintroduced one category at a time to identify personal triggers and tolerance thresholds. Proper sequencing, portion control, and symptom tracking are essential for accurate results (12).

Maintenance phase

The final phase focuses on establishing the least restrictive, most nutritionally complete diet possible while maintaining symptom control. Foods identified as well tolerated during reintroduction are incorporated regularly, supporting microbiome diversity and long-term gut health.

When a Low FODMAP Diet Is Helpful—and When It Is Not

When digestive symptoms reflect deeper gut dysfunction—not food alone

Digestive symptoms are rarely caused by food in isolation. In many cases, reactions to FODMAP-containing foods are influenced by underlying physiologic factors, including:

Gut motility and transit time

Microbiome balance and fermentation patterns

Intestinal inflammation and immune activation

Nervous system regulation and stress signaling

Hormonal and metabolic influences

A functional medicine approach helps determine whether FODMAP sensitivity is the primary driver of symptoms—or a downstream signal of deeper imbalance that requires targeted evaluation and treatment rather than long-term dietary restriction.

When applied in this context, a low FODMAP diet becomes a diagnostic and therapeutic tool, not a standalone solution.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to identify the root causes of your digestive symptoms and develop a sustainable, gut-healing plan.

Frequently Asked Questions About the Low FODMAP Diet

What is the low FODMAP diet and how does it work

The low FODMAP diet is a structured elimination diet designed to reduce fermentable carbohydrates that are poorly absorbed in the small intestine. These carbohydrates can trigger bloating, gas, and abdominal pain in people with IBS, SIBO, and other digestive disorders. By temporarily removing high FODMAP foods and then reintroducing them systematically, individuals can identify personal food triggers and reduce symptoms.

What conditions benefit most from the low FODMAP diet

The low FODMAP diet is most commonly used for irritable bowel syndrome and small intestinal bacterial overgrowth, but it may also help people with inflammatory bowel disease, celiac disease with persistent IBS-like symptoms, and leaky gut. It can be especially helpful for chronic bloating, gas, constipation, diarrhea, or alternating bowel patterns.

How long should I follow the low FODMAP diet

The elimination phase typically lasts two to six weeks. High FODMAP foods are then reintroduced gradually over six to eight weeks to identify which foods provoke symptoms. The diet is not intended to be followed long term, as prolonged restriction can increase the risk of nutrient deficiencies and negatively impact the gut microbiome.

What are the three phases of the low FODMAP diet

The diet is implemented in three phases. The elimination phase removes high FODMAP foods to calm symptoms. The reintroduction phase adds foods back one at a time to identify sensitivities. The maintenance phase focuses on a personalized, sustainable eating plan that avoids known triggers while supporting overall nutrition.

What are common high FODMAP foods to avoid

Common high FODMAP foods include onions, garlic, wheat, rye, regular dairy products, certain legumes, stone fruits such as cherries and peaches, and artificial sweeteners like high-fructose corn syrup.

What are safe low FODMAP foods

Low FODMAP foods often include pineapple, kiwi, potatoes, carrots, quinoa, oats, lactose-free dairy, eggs, tofu, and most unprocessed meats and seafood. Individual tolerance can vary, which is why reintroduction is an essential step.

Is the low FODMAP diet safe for children

The low FODMAP diet can be used in children, but only under the supervision of a qualified healthcare provider or dietitian. While studies suggest it may help children with IBD and other digestive conditions, professional guidance is necessary to prevent nutrient deficiencies and ensure proper growth.

Can I follow the low FODMAP diet on my own

Research shows that people who follow the low FODMAP diet with professional guidance have better symptom improvement and fewer nutritional risks. Working with a functional medicine practitioner or dietitian helps ensure the diet is applied correctly and personalized effectively.

How is the low FODMAP diet different from a gluten-free diet

A gluten-free diet eliminates gluten-containing grains such as wheat, barley, and rye. The low FODMAP diet is broader and focuses on fermentable carbohydrates, including some foods that may be gluten-free but still trigger digestive symptoms.

What are the risks of following the low FODMAP diet long term

Strict long-term avoidance of FODMAP foods can lead to vitamin and mineral deficiencies and reduced gut microbiome diversity. This is why the diet should be used as a short-term therapeutic tool, followed by careful reintroduction and personalization.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Gastroenterology – Nonceliac Gluten Sensitivity

Gut – Intestinal cell damage and systemic immune activation in individuals reporting sensitivity to wheat in the absence of coeliac disease

BMC Gastroenterology – An updated overview of spectrum of gluten-related disorders: clinical and diagnostic aspects

Gastroenterology – Efficacy of the low FODMAP diet in adults with irritable bowel syndrome

Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics – A diet low in FODMAPs reduces symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology – FODMAPs and functional gastrointestinal symptoms

Nutrients – Low FODMAP diet in inflammatory bowel disease: systematic review

Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition – Low FODMAP diet in children with inflammatory bowel disease

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology – Low FODMAP diet for persistent symptoms in treated celiac disease

Nutrients – Nutritional adequacy and long-term effects of the low FODMAP diet

Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics – Dietitian-led low FODMAP diet outcomes

Gastroenterology – Reintroduction phase accuracy in low FODMAP dietary intervention