Why Oxytocin Is a Key Regulator of Hormone Balance

How oxytocin influences cortisol, insulin, and sex hormones through the brain–endocrine axis

When people think about hormone imbalance, attention usually centers on estrogen, progesterone, testosterone, thyroid hormones, or cortisol. While these hormones are critical, they are not where regulation begins.

In clinical practice, symptoms such as fatigue, poor sleep, anxiety, weight gain, cycle irregularities, low libido, and mood changes frequently persist even when standard hormone labs fall within reference ranges. This occurs because hormones do not function independently. They operate within a hierarchical, brain-regulated system that prioritizes safety, stress signaling, and survival before reproduction, metabolism, or tissue repair.

One of the most overlooked regulators within this hierarchy is oxytocin.

Often reduced to the “love hormone,” oxytocin is more accurately understood as a central nervous system–mediated signaling hormone that communicates directly with the hypothalamus and influences how other hormones—particularly cortisol, insulin, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone—are released, suppressed, or prioritized.

From a systems-based perspective, oxytocin functions as a biological safety signal. When oxytocin signaling is sufficient, the brain interprets the internal and external environment as safe, allowing downstream hormonal systems to regulate efficiently. When oxytocin signaling is chronically low—due to prolonged stress, nervous system overload, inflammation, or social disconnection—the body shifts into a survival-dominant state. In this state, stress hormones rise, blood sugar regulation becomes impaired, and reproductive hormones are often deprioritized.

This framework helps explain why many individuals continue to struggle with hormone-related symptoms despite targeted dietary changes, supplements, or exercise programs. Without addressing upstream regulatory signals such as oxytocin, attempts to balance hormones often fail to produce lasting results.

This article explains how oxytocin influences hormonal regulation through the brain–endocrine axis, and why supporting oxytocin signaling is often necessary for balancing stress hormones, metabolic hormones, and sex hormones.

How the Brain Regulates Hormones: Understanding the Hormonal Hierarchy

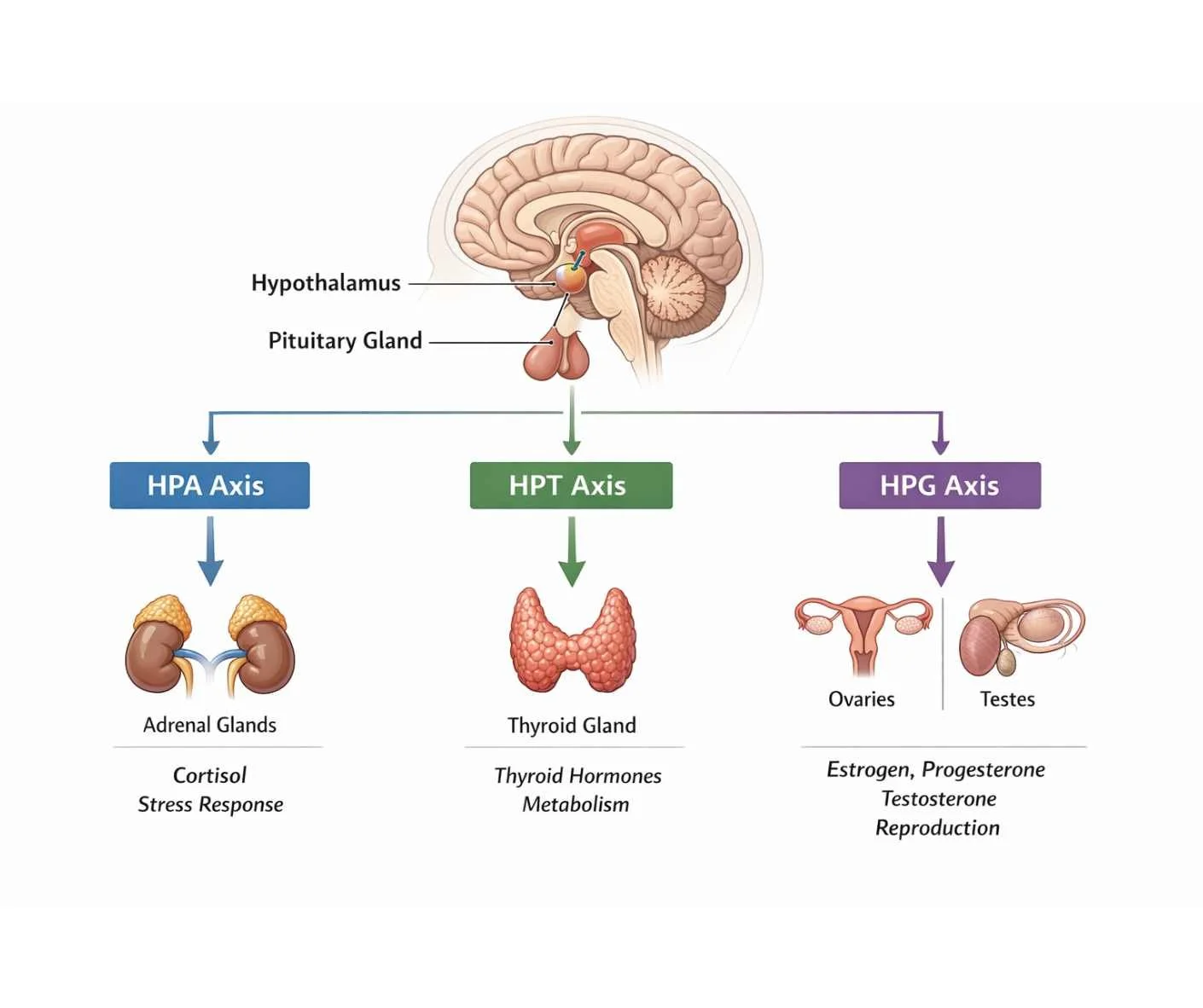

Hormones are often described as chemical messengers, but this definition is incomplete without understanding where hormonal control originates. Hormonal regulation is coordinated centrally through the brain—specifically the hypothalamus and pituitary glands—which continuously integrate signals from the body and environment to determine hormonal priorities (1).

This process is known as the hormonal hierarchy. Rather than all hormones operating equally, the brain evaluates incoming information related to:

perceived safety or threat

stress load

energy availability and blood sugar status

inflammation and immune activation

circadian rhythm and sleep quality

Based on these signals, the brain adjusts hormone output accordingly (2).

Central Control of Hormonal Signaling

At the top of the endocrine hierarchy is the hypothalamus, which acts as a command center linking the nervous system to hormonal regulation. The hypothalamus receives continuous input from the autonomic nervous system, immune signaling, metabolic cues, and sensory perception (3).

The pituitary gland translates this information into hormonal instructions that regulate endocrine organs, including:

adrenal glands

thyroid gland

pancreas

ovaries

testes

Through this feedback system, the brain determines which hormones are released, suppressed, or prioritized at any given time (4).

Survival First, Repair Second

When the brain perceives safety and adequate resources, hormonal communication remains adaptive and balanced. However, when it detects persistent stress—such as chronic psychological strain, sleep disruption, metabolic instability, inflammation, or toxic exposure—the hierarchy shifts (5).

In these conditions:

stress hormones are prioritized

blood sugar regulation becomes dominant

reproductive, growth, and repair hormones are often downregulated

This shift is protective in the short term, but maladaptive when sustained over time (6).

Why Hormone Labs Can Appear “Normal”

This hierarchical framework explains why hormone-related symptoms frequently occur despite hormone levels falling within laboratory reference ranges. The issue is not always hormone production, but how the brain is deploying hormonal signals in response to ongoing stressors (7).

Within this hierarchy, certain hormones exert disproportionate influence over how the entire system is regulated. One of the most influential—and most frequently overlooked—is oxytocin.

Oxytocin as an Upstream Regulatory Hormone

Oxytocin is commonly described as a social or bonding hormone, but this framing significantly underrepresents its role in hormonal regulation. From a physiological standpoint, oxytocin functions as an upstream regulatory signal that communicates directly with the hypothalamus, influencing how the brain prioritizes stress, metabolic, and reproductive hormones (8).

Unlike hormones that act primarily at peripheral target tissues, oxytocin exerts much of its influence centrally, shaping how the brain interprets safety, threat, and social connection. This interpretation has downstream consequences for the entire endocrine system.

Oxytocin as a Signal of Safety

Oxytocin is closely tied to parasympathetic nervous system activity. When oxytocin signaling is adequate, it sends a message to the brain that the internal and external environment is safe. In response, the hypothalamus adjusts hormonal output to support:

reduced stress hormone signaling

improved insulin sensitivity

reproductive hormone expression

tissue repair and recovery

This safety signaling allows the brain to shift out of survival mode and reallocate resources toward long-term health and resilience (9).

How Oxytocin Modulates Cortisol and Stress Hormones

One of oxytocin’s most important regulatory roles is its inhibitory effect on the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Adequate oxytocin signaling has been shown to dampen cortisol release by modulating hypothalamic and pituitary activity during stress responses (10).

When oxytocin levels are chronically low—due to persistent psychological stress, nervous system dysregulation, trauma, inflammation, or social isolation—the HPA axis remains more easily activated. This results in:

elevated or dysregulated cortisol patterns

increased blood sugar signaling

suppression of reproductive hormone output

impaired sleep and circadian rhythm disruption

Over time, this pattern contributes to the hormone imbalances commonly seen in chronic stress states (11).

Why Oxytocin Influences Sex Hormone Balance

Because reproductive hormones are lower on the hormonal hierarchy than stress hormones, they are particularly sensitive to upstream regulatory signals. When the brain perceives threat, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone signaling are often deprioritized, regardless of ovarian or testicular capacity (12).

By supporting oxytocin signaling, the brain receives consistent feedback that conditions are stable enough to allow reproductive hormones to be expressed appropriately. This is one reason oxytocin plays a foundational role in menstrual regularity, libido, fertility signaling, and hormonal transitions such as perimenopause and menopause (13).

Cortisol: How Chronic Stress Disrupts Hormonal Prioritization

Cortisol is the body’s primary stress-response hormone, regulated through the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis. Its role is adaptive in the short term—mobilizing energy, increasing alertness, and supporting survival during acute stress (14).

However, problems arise when cortisol signaling becomes chronically elevated or dysregulated.

In modern environments, stress is rarely short-lived or physical. Psychological pressure, poor sleep, metabolic instability, inflammation, toxic exposures, and constant cognitive demand repeatedly activate the HPA axis. When this activation becomes persistent, cortisol moves to the top of the hormonal hierarchy and begins to dominate endocrine signaling (15).

Cortisol’s Priority in the Hormonal Hierarchy

From a survival standpoint, cortisol takes precedence over nearly all other hormones. When cortisol demand is high, the brain reallocates resources toward immediate energy availability and away from processes that are not essential for short-term survival.

As a result:

reproductive hormones are downregulated

thyroid hormone signaling may be suppressed

tissue repair and immune balance are deprioritized

circadian rhythm regulation becomes impaired

This shift is protective during acute threat but becomes maladaptive when sustained over months or years (16).

Cortisol, Blood Sugar, and Insulin Signaling

One of cortisol’s most significant downstream effects is its impact on blood sugar regulation. Cortisol stimulates glucose release into the bloodstream to ensure rapid energy availability. In acute situations, this response is appropriate. Under chronic stress, however, repeated cortisol-driven glucose release contributes to insulin resistance and metabolic instability (17).

Elevated insulin signaling further reinforces cortisol dominance within the hormonal hierarchy, creating a feedback loop in which:

blood sugar becomes harder to regulate

inflammation increases

fat storage is promoted

sex hormone balance becomes more difficult to maintain

Over time, this pattern places additional strain on the endocrine system and amplifies hormone-related symptoms (18).

Why Chronic Cortisol Suppresses Sex Hormones

Reproductive hormones such as estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone are energetically expensive to produce and maintain. When cortisol signaling remains elevated, the brain interprets conditions as unfavorable for reproduction and long-term repair.

In this context:

progesterone is often the first hormone to decline

estrogen signaling becomes dysregulated

testosterone output may decrease or fluctuate

menstrual irregularities, low libido, and fertility challenges become more common

Importantly, these changes can occur even when the ovaries or testes are structurally healthy, reflecting regulatory suppression rather than organ failure (19).

This cortisol-driven suppression highlights why addressing stress physiology is foundational for hormone balance—and why upstream regulators, such as oxytocin, play a critical role in restoring hormonal prioritization.

Insulin and Metabolic Signaling: The Overlooked Driver of Hormone Imbalance

Insulin is often discussed solely in the context of blood sugar or diabetes, but its role in hormonal regulation extends far beyond glucose control. Insulin functions as a central metabolic signaling hormone, providing the brain with continuous feedback about energy availability and nutritional status (20).

Within the hormonal hierarchy, insulin operates closely alongside cortisol. When insulin signaling is stable and responsive, it supports metabolic flexibility and allows reproductive and thyroid hormones to function appropriately. When insulin signaling becomes chronically elevated or resistant, it reinforces a stress-dominant hormonal state, even in the absence of overt blood sugar abnormalities (21).

Insulin as a Signal of Energy Availability

From a regulatory perspective, insulin informs the brain whether sufficient energy is available to support growth, repair, and reproduction. When insulin sensitivity is intact, the brain interprets energy availability as adequate, allowing downstream hormonal systems to remain active (22).

However, repeated blood sugar spikes—driven by chronic stress, poor sleep, ultra-processed diets, inflammation, or sedentary behavior—can disrupt this signaling. Over time, the brain begins to receive conflicting metabolic signals, contributing to hormonal dysregulation (23).

How Insulin Resistance Amplifies Cortisol Dominance

Insulin resistance and cortisol dysregulation frequently coexist. Elevated cortisol increases glucose output, while insulin resistance impairs glucose uptake. This creates a feedback loop in which:

blood sugar remains elevated despite insulin release

insulin levels rise to compensate

inflammatory signaling increases

cortisol remains persistently activated

This cycle reinforces survival-oriented hormone prioritization and makes it increasingly difficult for sex hormones and thyroid hormones to be expressed effectively (24).

Insulin’s Impact on Sex Hormones

Insulin plays a direct role in sex hormone regulation, particularly through its effects on ovarian and adrenal signaling. Elevated insulin can increase androgen production, alter estrogen metabolism, and suppress progesterone signaling (25).

In women, this pattern is commonly associated with:

irregular menstrual cycles

ovulatory dysfunction

symptoms of estrogen dominance

reduced progesterone availability

These effects can occur even when fasting glucose and hemoglobin A1c remain within conventional reference ranges, highlighting the limitation of relying on basic metabolic labs alone (26).

Insulin, Thyroid Function, and Metabolic Rate

Insulin resistance also influences thyroid hormone activity. Chronic metabolic stress can impair the conversion of T4 to active T3 and increase reverse T3 production, contributing to symptoms of low metabolic rate despite “normal” thyroid labs (27).

This further compounds fatigue, weight changes, cold intolerance, and cognitive slowing—symptoms often attributed to isolated thyroid dysfunction rather than upstream metabolic signaling issues (28).

Why Metabolic Signaling Must Be Addressed for Hormone Balance

Because insulin communicates directly with both the brain and peripheral tissues, disrupted metabolic signaling can undermine hormonal balance across multiple systems simultaneously. Addressing insulin resistance is therefore not a standalone metabolic goal, but a foundational requirement for restoring endocrine regulation (29).

This metabolic layer helps explain why hormone-focused interventions often fail when blood sugar regulation, stress physiology, and nervous system signaling are not addressed together.

Sex Hormones Within the Hierarchy: Why Estrogen, Progesterone, and Testosterone Are Often the First to Shift

Sex hormones play essential roles in reproduction, metabolism, bone health, mood, cognition, and cardiovascular function. However, within the hormonal hierarchy, estrogen, progesterone, and testosterone are not prioritized for survival. Their expression depends heavily on upstream signals related to safety, stress load, and metabolic stability (30).

Because of this positioning, sex hormones are often the first to become dysregulated when the body is under chronic physiological strain—even when the ovaries or testes remain structurally healthy.

Why Reproductive Hormones Are Highly Sensitive to Stress

From a biological perspective, reproduction requires sufficient energy availability, stable blood sugar regulation, and a low-threat internal environment. When the brain detects chronic stress—via elevated cortisol, insulin resistance, inflammation, or nervous system dysregulation—it deprioritizes reproductive hormone signaling in favor of immediate survival needs (31).

This prioritization shift can lead to:

irregular or absent ovulation

shortened luteal phases

reduced progesterone production

altered estrogen signaling

fluctuations in testosterone output

These changes reflect regulatory suppression, not hormonal failure (32).

Progesterone: Often the First Hormone to Decline

Progesterone is particularly vulnerable to stress-driven shifts within the hierarchy. Adequate progesterone production depends on ovulation and sufficient metabolic and nervous system support. When cortisol and insulin demands are high, progesterone synthesis is often reduced, contributing to symptoms such as:

anxiety or mood instability

sleep disruption

heavy or irregular menstrual bleeding

shortened cycles or skipped cycles

This pattern is common in chronic stress states, perimenopause, and conditions characterized by metabolic strain (33).

Estrogen Dysregulation vs. Estrogen Deficiency

Estrogen-related symptoms are frequently described as estrogen “excess” or “deficiency,” but from a hierarchical standpoint, estrogen issues often reflect dysregulated signaling rather than absolute levels.

Chronic stress and insulin resistance can alter estrogen metabolism, receptor sensitivity, and clearance pathways, leading to symptoms such as:

breast tenderness

fluid retention

headaches

cycle irregularity

mood changes

These effects may occur even when serum estrogen levels appear within reference ranges (34).

Testosterone and Energy Signaling

Testosterone production in both women and men is closely tied to metabolic and nervous system signaling. Chronic cortisol elevation and insulin resistance can suppress testosterone synthesis or disrupt its downstream effects, contributing to:

reduced libido

loss of muscle mass

fatigue

mood changes

impaired recovery

As with other sex hormones, these changes often reflect regulatory inhibition rather than permanent glandular dysfunction (35).

Why Sex Hormone Therapy Alone Often Falls Short

Because sex hormones sit lower in the hormonal hierarchy, interventions that focus solely on replacing or suppressing estrogen, progesterone, or testosterone may provide temporary symptom relief without addressing the upstream drivers of imbalance.

Without restoring oxytocin signaling, stress regulation, and metabolic stability, sex hormone–focused approaches often fail to produce lasting improvement or require escalating intervention over time (35).

This reinforces the importance of addressing hormonal regulation from the top of the hierarchy down, rather than attempting to correct downstream imbalances in isolation.

How to Support Hormonal Regulation Naturally

Because hormones operate within a hierarchical, brain-regulated system, restoring balance requires addressing upstream regulation, not just downstream hormone levels. Supporting hormonal health begins with improving the signals the brain uses to determine safety, energy availability, and recovery capacity.

Rather than targeting individual hormones in isolation, a regulatory approach focuses on reducing chronic stress signaling, stabilizing metabolic inputs, and supporting nervous system balance so that hormonal communication can normalize over time.

Supporting Oxytocin Signaling

Oxytocin production is closely tied to perceived safety, connection, and parasympathetic nervous system activity. Practices that consistently signal safety to the brain can help shift the hormonal hierarchy away from survival dominance and toward repair and regulation.

Examples include:

safe, non-performative physical touch

restorative movement practices such as yoga or tai chi

slow, diaphragmatic breathing

meaningful social connection and conversation

time spent in calming environments

therapeutic bodywork

These inputs help reinforce oxytocin’s role as a regulatory signal, indirectly supporting cortisol modulation and downstream hormone balance.

Reducing Chronic Cortisol Activation

Lowering baseline stress signaling is essential for restoring hormonal prioritization. This does not require eliminating stress entirely, but rather improving the body’s ability to recover between stress exposures.

Supportive strategies include:

protecting sleep duration and consistency

avoiding excessive high-intensity training during periods of fatigue

creating predictable daily rhythms

addressing unresolved inflammatory or toxic stressors

allowing adequate recovery after physical or emotional strain

When cortisol signaling becomes more adaptive, reproductive and metabolic hormones are more likely to re-enter balanced expression.

Stabilizing Metabolic Signaling

Consistent blood sugar regulation helps prevent insulin-driven reinforcement of stress physiology. Supporting metabolic stability allows the brain to interpret energy availability as sufficient, reducing survival-based hormonal suppression.

Helpful approaches may include:

regular, protein-balanced meals

minimizing large blood sugar swings

aligning eating patterns with circadian rhythms

avoiding prolonged under-fueling during high-demand periods

These strategies support insulin sensitivity and reduce metabolic noise within the hormonal hierarchy.

Why Personalization Matters

Hormonal regulation is highly individualized. Factors such as life stage, stress history, metabolic health, environmental exposures, and nervous system tone influence how the hierarchy responds. What supports regulation for one person may be insufficient—or counterproductive—for another.

This is why generalized hormone protocols often fail, while personalized, systems-based approaches are more likely to produce sustainable improvement.

Why Hormone Balance Requires a Systems-Based Approach

Hormonal symptoms rarely exist in isolation. Fatigue, mood changes, sleep disruption, weight fluctuations, cycle irregularities, low libido, and fertility challenges are often treated as separate problems, but from a regulatory perspective, they commonly reflect a shared upstream imbalance.

As outlined throughout this article, hormones are governed by a hierarchy that prioritizes survival, stress response, and energy availability before reproduction, repair, and long-term resilience. When this hierarchy is disrupted, addressing individual hormone levels alone is often insufficient.

A systems-based approach recognizes that hormone balance depends on the integration of multiple regulatory systems, including:

nervous system signaling

stress physiology

metabolic regulation

circadian rhythm integrity

immune and inflammatory balance

When these systems are under chronic strain, hormonal communication becomes fragmented. Symptoms may fluctuate, labs may appear inconclusive, and isolated interventions may provide only temporary relief.

→ Women’s Health & Fertility Support

Why Single-Hormone Solutions Often Fall Short

Approaches that focus exclusively on replacing, suppressing, or stimulating individual hormones may overlook the regulatory signals that determine how those hormones are expressed and utilized. Without restoring upstream regulation, downstream hormone-focused strategies can become increasingly complex without producing durable results.

This helps explain why some individuals experience persistent symptoms despite “normal” labs, lifestyle changes, or targeted supplementation. The issue is not a lack of effort, but a mismatch between where intervention is applied and where dysregulation originates.

When a Broader Evaluation May Be Appropriate

A systems-based evaluation may be warranted when hormone-related symptoms are persistent, recurrent, or resistant to conventional approaches—particularly when symptoms involve multiple systems or fluctuate with stress, sleep, or metabolic demand.

Rather than asking which hormone is “out of range,” this approach asks:

what signals the brain is responding to

which systems are increasing regulatory strain

what factors are limiting recovery and resilience

Addressing these questions allows hormonal balance to emerge as a downstream outcome of improved regulation, rather than a target forced through isolated intervention. Approaches that support nervous system regulation—including targeted lifestyle strategies and regulated therapeutic inputs—can help reinforce these upstream signals.

→ Acupuncture & Nervous System Regulation

How a Systems-Based Approach Supports Hormonal Regulation

Hormonal regulation is complex, and persistent symptoms often reflect upstream dysregulation rather than isolated hormone deficiencies. When stress physiology, metabolic signaling, nervous system balance, and environmental load are not addressed together, hormone-focused interventions may fall short.

A systems-based evaluation can help clarify which regulatory signals are contributing to ongoing symptoms and whether a more integrative approach is appropriate.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Oxytocin and Hormone Balance

Can low oxytocin cause hormone imbalance?

Low oxytocin does not directly “cause” hormone imbalance, but it can contribute to upstream regulatory dysfunction. Oxytocin helps signal safety to the brain. When oxytocin signaling is chronically low, stress hormones and metabolic hormones are often prioritized, which can suppress or dysregulate sex hormone signaling over time.

Why do my hormone labs look normal if I still have symptoms?

Standard hormone labs measure circulating hormone levels, not how the brain is prioritizing or deploying those hormones. Stress, metabolic instability, inflammation, and nervous system dysregulation can impair hormone signaling and tissue response even when lab values fall within reference ranges.

Is oxytocin only related to bonding and relationships?

No. While oxytocin plays an important role in social bonding, it also functions as a central regulatory hormone that influences stress response, autonomic nervous system balance, and downstream endocrine signaling. Its effects extend well beyond emotional connection.

Can stress lower oxytocin levels?

Chronic stress can reduce oxytocin signaling by keeping the nervous system in a threat-dominant state. When stress responses remain persistently activated, the body is less able to generate the parasympathetic conditions associated with oxytocin release.

How does oxytocin affect cortisol?

Oxytocin helps modulate the stress response by signaling safety to the brain. When oxytocin signaling is adequate, cortisol release tends to be more adaptive. When oxytocin signaling is impaired, cortisol activation can become exaggerated or prolonged.

Can improving oxytocin help with menstrual irregularities?

Supporting oxytocin signaling may help indirectly by reducing stress-driven suppression of reproductive hormones. Menstrual irregularities often reflect upstream regulatory strain rather than isolated ovarian dysfunction, particularly when cycles fluctuate with stress or lifestyle changes.

Does oxytocin play a role in perimenopause or menopause?

Yes. During hormonal transitions, the nervous system becomes more sensitive to stress and regulatory load. Adequate oxytocin signaling may help buffer stress responses and support hormonal adaptation during perimenopause and menopause, even as estrogen and progesterone levels change.

Is oxytocin something you can “supplement”?

Oxytocin is primarily regulated through physiological and nervous system inputs, not oral supplementation. Lifestyle, environmental, and regulatory factors that signal safety and connection to the brain are the most relevant influences on oxytocin signaling.

Why do hormone-focused treatments sometimes stop working?

Hormone-focused treatments may lose effectiveness if upstream regulatory issues—such as chronic stress, metabolic instability, or nervous system dysregulation—are not addressed. Without restoring regulatory balance, downstream hormone interventions may require increasing intensity over time.

When should someone consider a systems-based hormone evaluation?

A broader evaluation may be appropriate when hormone-related symptoms are persistent, fluctuate with stress, involve multiple systems, or fail to improve despite standard lifestyle or hormone-focused approaches. These patterns often suggest upstream regulatory imbalance rather than isolated hormone deficiency.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Endocrine Reviews – Neuroendocrine regulation of hypothalamic–pituitary hormone secretion

Physiological Reviews – Organization and function of the hypothalamic–pituitary axis

Nature Reviews Endocrinology – Central regulation of endocrine systems by the brain

Endocrine Reviews – Stress and hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis regulation

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Chronic stress and dysregulation of hormonal signaling

Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology – Oxytocin: central regulation of stress and social behavior

Physiological Reviews – Oxytocin signaling in the central nervous system

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Oxytocin modulation of cortisol and stress responses

Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism – Hormonal hierarchy and prioritization under stress

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Why normal hormone levels do not ensure normal hormone action

Endocrinology – Hypothalamic integration of metabolic and stress signals

Endocrine Reviews – Cortisol regulation and chronic stress physiology

Nature Reviews Endocrinology – Metabolic stress and endocrine adaptation

Diabetes – Cortisol, glucose metabolism, and insulin resistance

Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism – Insulin as a signaling hormone beyond glucose control

Diabetes Care – Insulin resistance as a systemic endocrine disorder

Endocrine Reviews – Interactions between insulin signaling and reproductive hormones

Endocrine Connections – Metabolic stress and thyroid hormone regulation

Thyroid – Impaired T4-to-T3 conversion during metabolic and inflammatory stress

Human Reproduction Update – Stress effects on ovulation and reproductive hormone signaling

Endocrinology – Progesterone suppression during chronic stress states

Fertility and Sterility – Neuroendocrine control of the menstrual cycle

The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Androgen regulation under metabolic stress

Neuroendocrinology – Central suppression of reproductive hormones during stress

Menopause – Neuroendocrine adaptation during perimenopause and menopause

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews – Nervous system safety signaling and endocrine regulation

Frontiers in Neuroscience – Parasympathetic regulation and hormonal balance

Trends in Cognitive Sciences – Brain interpretation of safety and threat in physiological regulation

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology – Integrated stress–metabolic–reproductive axis regulation

Annual Review of Physiology – Systems-level regulation of endocrine health

Endocrine Reviews – Systems-based models of hormonal dysregulation

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Nervous system regulation as a determinant of endocrine function

Nature Reviews Neuroscience – Neural control of homeostasis and endocrine signaling

Trends in Neurosciences – Brain–body integration in stress and hormonal adaptation

The New England Journal of Medicine – Neuroendocrine pathways linking stress, metabolism, and reproduction