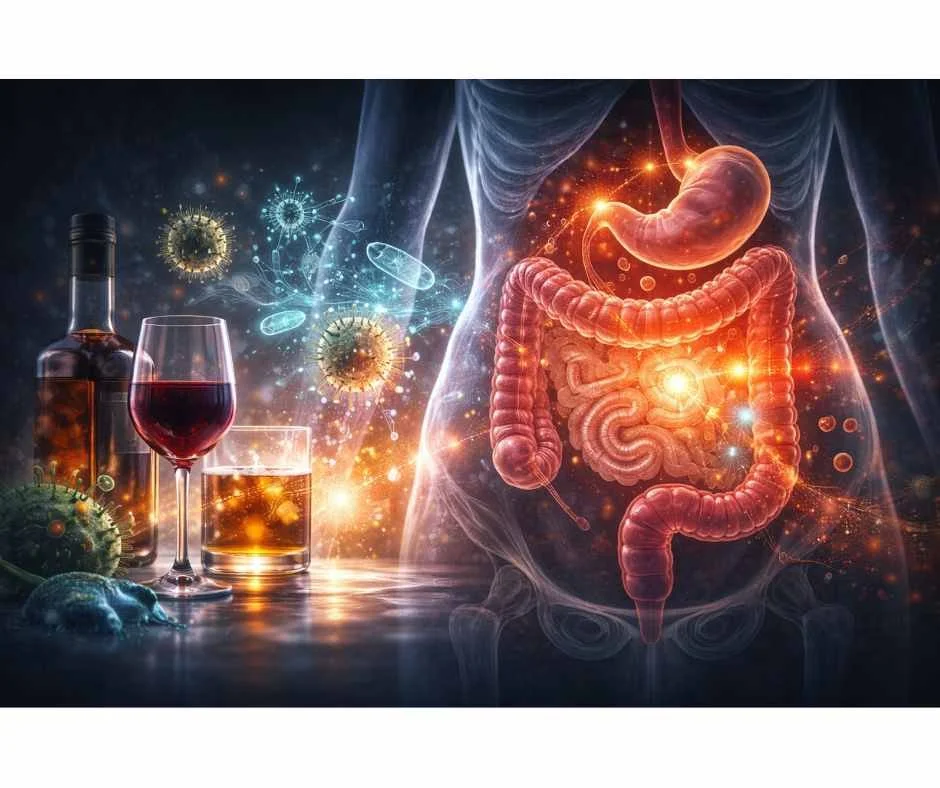

Alcohol and Gut Health: How Drinking Drives Leaky Gut and Inflammation

How alcohol disrupts the gut microbiome, intestinal barrier, and gut–brain signaling—often without digestive symptoms

Alcohol is widely consumed and socially normalized, often without consideration of its cumulative physiological effects. Many individuals drink regularly without tracking frequency or quantity, particularly when intake is perceived as “moderate” or limited to social settings.

From a gut health perspective, however, alcohol represents a significant and underrecognized stressor.

Alcohol directly alters the gut microbiome, damages the intestinal barrier, and promotes inflammatory signaling within the gastrointestinal tract. These effects are not limited to heavy or chronic drinking. Even moderate alcohol intake can disrupt microbial balance, increase intestinal permeability, and impair immune regulation within the gut—often before overt digestive symptoms develop.

Because the gut plays a central role in immune function, nutrient absorption, and systemic inflammation, alcohol-related gut disruption can have far-reaching consequences. Symptoms such as bloating, reflux, food sensitivities, fatigue, brain fog, joint pain, and heightened inflammatory responses may reflect underlying gut dysfunction rather than isolated digestive issues.

This article examines how alcohol affects gut health at a physiological level, including its impact on the microbiome, intestinal barrier integrity, inflammation, and the gut–liver axis. Understanding these mechanisms helps explain why gut-related symptoms often persist despite dietary changes—and why addressing alcohol exposure is an important, though frequently overlooked, component of restoring gut health.

Alcohol’s Overlooked Impact on Gut Integrity

How Moderate Alcohol Intake Disrupts Gut Integrity

Alcohol-related gut damage does not require heavy or chronic drinking to occur. Even moderate, regular alcohol intake can disrupt the gut microbiome, weaken tight junctions between intestinal cells, and increase intestinal permeability. These changes often develop gradually and do not immediately produce severe digestive symptoms, which allows gut barrier damage to progress unnoticed (1).

Because moderate alcohol use is socially normalized and rarely framed as a physiological stressor, its cumulative impact on gut integrity is frequently underestimated. Over time, repeated low-grade exposure can impair barrier repair mechanisms, increase inflammatory signaling, and reduce microbial resilience—setting the stage for chronic gut dysfunction despite otherwise healthy dietary habits (2).

Why Alcohol-Related Gut Symptoms Are Often Missed

Gut-related symptoms linked to alcohol exposure are commonly non-specific and delayed, making causal connections difficult to recognize. Bloating, reflux, food sensitivities, fatigue, joint pain, brain fog, or inflammatory flares may appear hours to days after alcohol consumption, rather than immediately following intake. As a result, alcohol is rarely identified as a contributing factor (3).

In addition, conventional evaluations typically do not assess microbiome composition, intestinal permeability, or immune activation at the gut level. When standard labs appear normal, symptoms are often attributed to stress, diet, or unrelated conditions—allowing alcohol-related gut dysfunction to persist without targeted intervention (4).

How Alcohol Consumption Harms the Gut and Overall Health

Alcohol is one of the most widely consumed substances in the United States, with the majority of adults reporting at least occasional use. While short-term effects may include reduced social inhibition, even moderate, regular alcohol intake can exert measurable and cumulative effects on gut physiology and digestive health over time (1,2).

From a clinical perspective, alcohol exposure places direct stress on the gastrointestinal tract, alters microbial balance, and disrupts intestinal barrier integrity—often long before overt digestive symptoms or abnormal standard laboratory findings appear.

Alcohol Metabolism and Its Direct Effects on Gut Tissue

Alcohol is not treated as a nutrient by the body. It is recognized as a toxin and prioritized for rapid metabolism and elimination.

Step 1: Alcohol Conversion to Acetaldehyde

Once ingested, alcohol is absorbed through the stomach and small intestine and metabolized primarily in the liver and upper gastrointestinal tract.

Alcohol dehydrogenase (ADH) converts ethanol into acetaldehyde

Acetaldehyde is a highly reactive and toxic compound

This intermediate is associated with cellular damage and carcinogenic risk (3,4)

Step 2: Acetaldehyde Detoxification to Acetate

Acetaldehyde is then metabolized by aldehyde dehydrogenase (ALDH) into acetate, which is further broken down into carbon dioxide and water for elimination.

While this pathway allows alcohol to be cleared, it comes at a significant physiological cost.

Step 3: Disruption of Cellular Metabolism

Alcohol metabolism alters normal energy production by:

Shifting cells away from glucose metabolism

Increasing reliance on acetate as an energy source

Disrupting mitochondrial function

Increasing oxidative stress and inflammatory signaling (5,6)

At the level of the gut, acetaldehyde and related byproducts directly damage epithelial cells and interfere with normal digestive and immune signaling.

Alcohol, the Gut Microbiome, and Intestinal Inflammation

Chronic alcohol exposure disrupts the gut microbiome—the complex ecosystem of bacteria responsible for digestion, immune regulation, and barrier maintenance.

How Alcohol Alters the Microbiome

Alcohol contributes to dysbiosis by:

Reducing beneficial commensal bacteria

Promoting overgrowth of pathogenic or pro-inflammatory species

Increasing production of endotoxins and inflammatory metabolites

Downstream Effects of Alcohol-Induced Dysbiosis

Over time, these changes contribute to:

Breakdown of the intestinal epithelial barrier

Increased intestinal permeability

Impaired nutrient absorption and cellular stress

Dysregulated gut-associated immune responses (4,7)

As barrier integrity declines, microbial byproducts such as lipopolysaccharides (LPS) gain access to the bloodstream.

Alcohol-Driven Systemic Inflammation and Immune Activation

Once circulating, these inflammatory compounds trigger hepatic and systemic immune responses, including the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

Clinically, this inflammatory cascade is associated with:

Increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”)

Heightened immune activation

Worsening of autoimmune and inflammatory conditions (2)

Alcohol, Gut Permeability, and the Gut–Brain Axis

The gut and brain are closely connected through immune, metabolic, and neural signaling pathways. When alcohol disrupts gut barrier integrity and microbial balance, these signals are altered in ways that directly affect brain function and behavior (8,9).

How Increased Gut Permeability Affects the Brain

As alcohol-related intestinal permeability increases, inflammatory molecules and microbial byproducts enter systemic circulation. These compounds:

Activate immune signaling pathways

Increase circulating pro-inflammatory cytokines

Alter blood–brain barrier integrity

Interfere with neurotransmitter balance and stress regulation (9,10)

Over time, this inflammatory signaling contributes to changes in brain chemistry and nervous system regulation.

Clinical Effects of Gut–Brain Axis Disruption

From a clinical perspective, gut-mediated inflammation related to alcohol exposure is associated with:

Anxiety and heightened stress reactivity

Mood instability and irritability

Sleep disruption and altered circadian signaling

Cognitive changes such as brain fog or reduced focus

Increased cravings and difficulty moderating intake (10,11)

Importantly, these symptoms often emerge gradually and may be misattributed to psychological stress, aging, or unrelated mental health concerns rather than underlying gut dysfunction.

How Gut Barrier Damage Amplifies Alcohol’s Systemic Effects

When gut integrity is compromised, the body’s ability to regulate inflammation, detoxification, and immune tolerance is significantly reduced. This creates a self-reinforcing cycle:

Alcohol damages the gut barrier

Increased permeability drives systemic inflammation

Inflammation impairs detoxification and metabolic resilience

Reduced resilience worsens sensitivity to alcohol exposure (9,12)

Clinically, this helps explain why some individuals experience escalating symptoms over time despite unchanged or “moderate” drinking patterns.

For a broader, systems-based overview of how alcohol affects detoxification, nutrient status, sleep physiology, and nervous system regulation across the body, explore

→ The Hidden Effects of Alcohol on Whole-Body Health

How Gut Damage Worsens Alcohol-Related Nutrient Depletion

Damage to the intestinal lining does not occur in isolation. When alcohol disrupts gut barrier integrity and microbial balance, the body’s ability to absorb, activate, and utilize essential nutrients is significantly impaired (13).

Impaired Nutrient Absorption From Alcohol-Related Gut Damage

Alcohol-related inflammation and increased intestinal permeability interfere with nutrient transport across the gut lining. This reduces absorption of:

Minerals such as magnesium, zinc, and selenium

Water-soluble vitamins including B vitamins and vitamin C

Fat-soluble vitamins that depend on intact digestion and bile flow (13,14)

Even when dietary intake appears adequate, compromised gut function can prevent nutrients from reaching systemic circulation and target tissues.

Increased Inflammatory Demand and Nutrient Loss

At the same time, alcohol-induced gut inflammation increases the body’s demand for nutrients involved in:

Antioxidant defense

Immune regulation

Detoxification and tissue repair

This creates a mismatch between supply and demand—nutrients are both less available and more rapidly consumed under inflammatory conditions (14,15).

Alcohol-Related Disruption of the Gut–Liver Axis

The gut and liver are functionally connected through the portal circulation. When microbial byproducts and inflammatory compounds pass through a compromised gut barrier, they place additional strain on hepatic detoxification pathways.

Clinically, this gut–liver stress axis contributes to:

Reduced nutrient storage and activation

Impaired bile flow and fat digestion

Altered metabolism of vitamins and minerals required for detoxification (15,16)

Clinical Implications of Alcohol-Related Gut Dysfunction

When gut dysfunction and nutrient depletion occur together, symptoms often intensify and become more persistent. Patients may experience:

Fatigue that does not respond to diet alone

Increased sensitivity to stress or alcohol

Worsening sleep quality and mood regulation

Reduced resilience to illness or inflammation (16)

From a systems-based perspective, addressing gut integrity is a prerequisite for restoring nutrient balance and metabolic stability in individuals affected by alcohol-related health stress.

→ Functional & Integrative Medicine

Why Symptoms Often Occur Without Obvious Digestive Complaints

Alcohol-related gut dysfunction does not always present with classic gastrointestinal symptoms such as pain, bloating, or altered bowel habits. In many cases, intestinal permeability, microbial imbalance, and low-grade inflammation develop silently and exert their effects systemically rather than locally (17).

Subclinical Gut Dysfunction and Systemic Effects

When gut barrier integrity is compromised, inflammatory signaling and metabolic disruption can occur even in the absence of overt digestive distress. This is because the gut plays a central regulatory role in:

Immune tolerance and inflammatory control

Neurotransmitter production and nervous system signaling

Hormone metabolism and stress regulation

Detoxification and nutrient utilization (17,18)

As a result, symptoms often emerge in distant systems rather than being perceived as “digestive” in nature.

Common Non-Gastrointestinal Presentations

Clinically, individuals with alcohol-related gut dysfunction may report:

Fatigue or reduced stress tolerance

Anxiety, irritability, or mood changes

Poor sleep quality or circadian disruption

Brain fog or reduced cognitive clarity

Increased sensitivity to alcohol or other stressors (18,19)

Because these symptoms are nonspecific, they are frequently attributed to lifestyle stress, aging, or mental health factors rather than underlying gut-mediated inflammation.

Why Standard Testing Misses Alcohol-Related Gut Dysfunction

Routine laboratory testing may appear normal in early or moderate gut dysfunction. Intestinal permeability, microbiome imbalance, and low-grade inflammation are not typically captured by conventional screening tests, allowing dysfunction to progress unnoticed (19).

From a clinical standpoint, this explains why individuals may feel progressively worse over time despite “normal” results and otherwise healthy behaviors.

Clinical Implications of Alcohol-Related Gut Dysfunction

When gut dysfunction, inflammation, and nutrient depletion coexist, symptoms tend to become more persistent and less responsive to surface-level interventions.

Addressing gut integrity and microbial balance is therefore a foundational step in restoring metabolic resilience, immune regulation, and neurological stability in individuals affected by alcohol-related physiological stress (20).

When Alcohol-Related Gut Dysfunction Requires Clinical Support

Alcohol-related gut disruption and metabolic stress can contribute to a wide range of symptoms affecting immune regulation, neurological function, detoxification capacity, and overall physiological resilience—even in individuals who do not meet criteria for alcohol dependence (21).

At Denver Sports and Holistic Medicine, evaluation begins with a comprehensive, systems-based assessment. When clinically appropriate, this may include functional laboratory testing to assess gut integrity, inflammatory signaling, nutrient status, and metabolic patterns that are often not captured through standard testing alone.

Care is individualized and integrative, incorporating evidence-informed therapies such as acupuncture, targeted nutritional strategies, detoxification support, and lifestyle interventions designed to restore balance across interconnected body systems.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Based on clinical findings, a personalized plan is developed to address identified imbalances, reduce long-term risk, and support restoration of gut function and systemic health.

Frequently Asked Questions About Alcohol and Gut Health

Can alcohol damage your gut even if you don’t have digestive symptoms?

Yes. Alcohol-related gut damage often develops silently. Changes in gut permeability, microbiome balance, and inflammatory signaling can occur without obvious symptoms such as bloating or pain, while still affecting immune function, mood, sleep, and overall resilience.

How does alcohol affect the gut microbiome?

Alcohol alters the balance of gut bacteria by reducing beneficial species and promoting inflammatory or pathogenic organisms. Over time, this microbial imbalance contributes to intestinal inflammation, impaired barrier function, and altered immune signaling.

What is leaky gut, and how is alcohol involved?

Leaky gut refers to increased intestinal permeability, where the gut lining becomes less effective at keeping inflammatory compounds out of circulation. Alcohol and its toxic byproducts directly damage tight junctions in the gut lining, increasing permeability and systemic inflammation.

Can alcohol-related gut damage affect the brain?

Yes. The gut and brain communicate through immune, metabolic, and neural pathways. Alcohol-related gut inflammation can alter neurotransmitter balance, increase inflammatory signaling to the brain, and contribute to anxiety, mood changes, sleep disruption, and cognitive symptoms.

Does alcohol-related gut dysfunction affect nutrient absorption?

Alcohol-related inflammation and barrier damage impair the absorption of vitamins and minerals, even when dietary intake is adequate. This can worsen fatigue, stress tolerance, immune resilience, and metabolic function over time.

Why do alcohol-related gut issues worsen over time?

Alcohol-related gut damage creates a feedback loop. Increased permeability drives inflammation, inflammation impairs detoxification and immune regulation, and reduced resilience increases sensitivity to alcohol and other stressors—leading to progressive symptoms even without increased intake.

Can gut health improve after reducing alcohol intake?

Gut function can improve when alcohol exposure is reduced and underlying imbalances are addressed. Recovery depends on the degree of damage, overall health, and whether gut integrity, microbiome balance, and inflammation are actively supported rather than left to self-correct.

Is gut testing necessary for alcohol-related gut symptoms?

Not always, but targeted testing can help identify intestinal permeability, microbial imbalance, inflammation, and related patterns that are not visible on routine labs—especially when symptoms are systemic rather than digestive.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism- Alcohol Facts and Statistics

Alcohol Research: Current Reviews- Alcohol, Acetaldehyde, and Gastrointestinal Toxicity

Hepatology- Ethanol Metabolism and Acetaldehyde-Induced Tissue Injury

Gut- Alcohol-Induced Intestinal Permeability and Microbiome Disruption

Free Radical Biology & Medicine- Oxidative Stress Mechanisms in Alcohol-Related Gut Injury

Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology- Alcohol, Dysbiosis, and Intestinal Inflammation

The Journal of Immunology- Gut Barrier Dysfunction and Systemic Immune Activation

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology- The Gut–Liver–Brain Axis in Alcohol-Related Disease

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity- Inflammatory Signaling Linking Gut Dysfunction and Neurobehavioral Change

Alcohol Research: Current Reviews- Alcohol Use and the Gut–Brain Axis

Neurogastroenterology & Motility- Intestinal Permeability and Neuroimmune Communication

Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology- Subclinical Gut Dysfunction and Systemic Symptoms

The Journal of Nutrition- Impaired Nutrient Absorption in Alcohol-Related Gut Injury

Hepatology Communications- Portal Endotoxemia and Hepatic Inflammatory Response

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition- Gut Integrity, Inflammation, and Metabolic Health

Gut Microbes- Dysbiosis, Endotoxins, and Systemic Inflammation

Frontiers in Immunology- Intestinal Barrier Dysfunction and Immune Dysregulation

Psychoneuroendocrinology- Gut–Brain Signaling, Stress, and Alcohol Exposure

The Lancet Gastroenterology & Hepatology- Alcohol Consumption and Multisystem Gastrointestinal Effects

Carcinogenesis- Acetaldehyde-Induced DNA Damage in Gastrointestinal Tissue