How Added Sugar Disrupts Metabolic Health, Hormones, and Energy Regulation

Why chronic sugar intake contributes to fatigue, blood sugar instability, inflammation, and long-term metabolic dysfunction—and what matters clinically

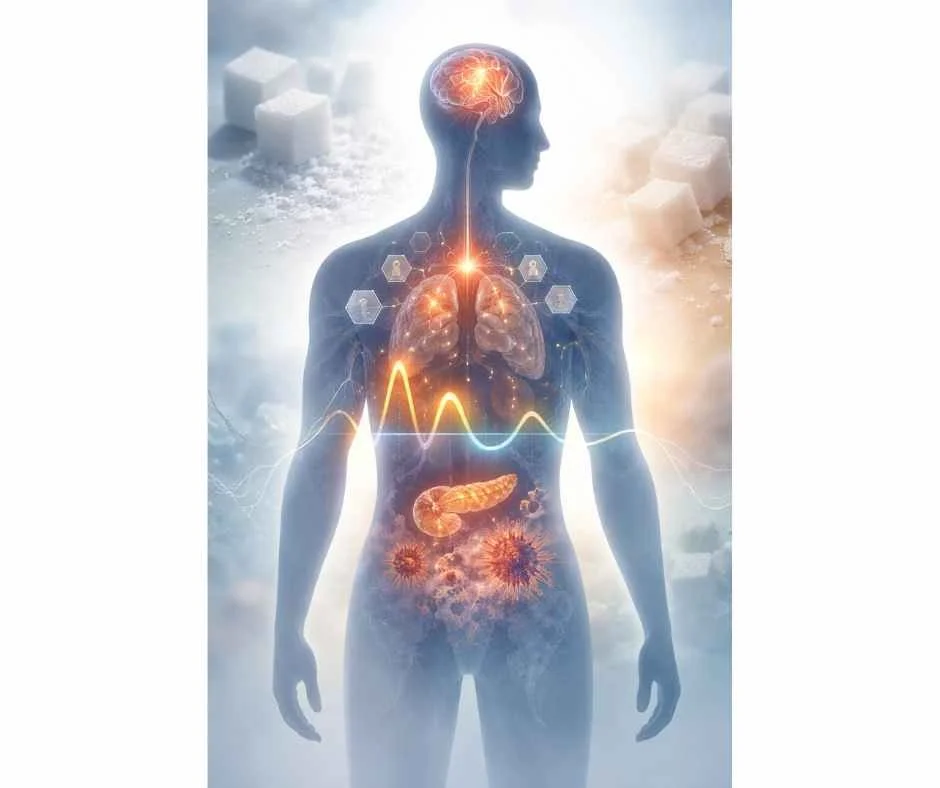

Added sugar is no longer just a nutrition concern—it is a metabolic stressor that quietly interferes with how the body regulates energy, hormones, inflammation, and long-term resilience.

Many individuals reduce sugar believing it is primarily about weight, willpower, or “empty calories.” Clinically, the issue is far more nuanced. Chronic exposure to added sugar—especially in processed and liquid forms—alters blood sugar signaling, insulin responsiveness, stress hormone output, and cellular energy production, often long before standard labs flag a problem.

This helps explain a common and frustrating pattern: persistent fatigue, afternoon crashes, brain fog, anxiety, mood swings, or stubborn inflammation despite “normal” blood work and generally healthy habits. These symptoms are not character flaws or inevitable consequences of aging. They are often early signs of metabolic dysregulation, where the body’s ability to adapt to daily demands becomes impaired.

Rather than acting in isolation, sugar influences multiple interconnected systems at once—blood sugar regulation, nervous system signaling, hormonal communication, gut integrity, immune activity, and mitochondrial energy production. Over time, this cumulative strain increases vulnerability to insulin resistance, hormonal imbalance, metabolic syndrome, fatty liver disease, and other chronic conditions.

This article explains how added sugar disrupts metabolic health at a systems level, why symptoms can appear long before disease is diagnosed, and what matters clinically when addressing sugar-related fatigue, hormonal instability, and energy dysregulation within a root-cause framework.

Why Added Sugar Is a Metabolic Stressor—Not Just a “Calorie”

Added sugar is often discussed as a simple source of excess calories, but this framing misses the more important clinical reality. The primary issue is not energy intake—it is how repeated exposure to added sugar disrupts regulatory systems that control blood sugar, hormones, inflammation, and cellular energy balance (1,2).

From a metabolic perspective, added sugar acts as a persistent signaling stressor. Each exposure triggers insulin release, influences stress hormone output, and places demand on the nervous system to maintain stability. When this pattern occurs frequently, regulation becomes less efficient, requiring greater physiological effort to achieve the same balance.

Added Sugar vs. Naturally Occurring Sugars

Sugars that occur naturally in whole foods—such as fruit—are consumed within a matrix of fiber, water, and micronutrients that slow absorption and moderate blood sugar responses. This context supports more gradual glucose entry into circulation and reduces the intensity of insulin signaling.

Added sugars lack this protective framework. They are absorbed rapidly, creating sharper blood sugar fluctuations and greater regulatory demand. Over time, this pattern contributes to metabolic strain rather than metabolic support.

The distinction is not ideological or nutritional—it is physiological.

Liquid Sugar, Frequency of Exposure, and Metabolic Load

Liquid forms of sugar are particularly disruptive because they bypass many of the body’s satiety and digestive feedback mechanisms. Sweetened beverages, fruit juices, and sugar-laden coffee drinks deliver concentrated glucose loads quickly, often without triggering fullness or reducing subsequent intake (3,4).

Equally important is frequency. Repeated sugar exposure throughout the day prevents blood sugar and insulin from returning to baseline. Instead of discrete metabolic events, the body is pushed into a near-continuous state of regulation, reducing metabolic flexibility and resilience.

Why the Body Responds Differently Over Time

In early stages, the body compensates effectively. Insulin output increases, stress hormones rise, and energy may even feel temporarily enhanced. Over time, however, these compensatory mechanisms lose efficiency.

As regulatory capacity declines, symptoms often emerge—fatigue, brain fog, cravings, irritability, and reduced stress tolerance—even when standard labs remain within reference ranges (5).

Understanding added sugar as a metabolic stressor, rather than a calorie problem or personal failure, provides a more accurate framework for addressing fatigue, hormonal instability, and long-term metabolic risk.

How Sugar Disrupts Blood Sugar and Insulin Signaling

When added sugar enters the bloodstream, it triggers a coordinated hormonal response designed to keep blood glucose within a narrow range. The pancreas releases insulin, signaling cells to absorb glucose for immediate energy or storage. In isolation, this process is normal and adaptive.

Problems arise when this signaling is activated too frequently.

Repeated sugar exposure forces insulin to remain elevated for longer periods, reducing cellular responsiveness over time. As insulin signaling becomes less efficient, higher amounts are required to achieve the same effect—a process known as insulin resistance (6,7).

Importantly, insulin resistance does not begin as a disease state. It develops gradually as a regulatory strain, often without abnormal fasting glucose or A1C values.

What Happens After a Blood Sugar Spike

After a rapid rise in blood glucose, insulin works to clear sugar from circulation. When glucose drops too quickly—or overshoots baseline—counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline are released to restore balance (8).

This cycle contributes to:

Energy crashes

Shakiness or irritability

Hunger shortly after eating

Cognitive fog or reduced focus

Over time, repeated spikes and crashes increase stress signaling throughout the nervous system and impair metabolic stability.

Insulin Resistance as a Progressive Process

Insulin resistance develops along a spectrum. Early on, the body compensates by producing more insulin. Blood sugar may remain within reference ranges, masking the underlying dysfunction (9).

As resistance progresses:

Fat storage increases, particularly viscerally

Appetite regulation becomes impaired

Energy availability at the cellular level declines

This helps explain why fatigue and weight changes often precede a formal metabolic diagnosis by years.

Why “Normal Labs” Don’t Rule Out Dysregulation

Standard lab markers assess outcomes, not regulation. Fasting glucose and A1C reflect late-stage changes, not early signaling inefficiencies (10).

Clinically, individuals may experience fatigue, brain fog, mood instability, or reactive hypoglycemia long before conventional thresholds are crossed. These symptoms represent loss of metabolic flexibility, not failure of willpower or lifestyle discipline.

Recognizing early insulin signaling disruption allows intervention before metabolic disease becomes entrenched.

Sugar, Energy Crashes, and Chronic Fatigue

One of the most common early signs of sugar-related metabolic dysregulation is unstable energy. Rather than sustained vitality, energy becomes episodic—characterized by brief spikes followed by predictable crashes.

This pattern is often misattributed to poor sleep, stress, aging, or lack of motivation. Clinically, it reflects impaired coordination between blood sugar regulation, stress hormones, and cellular energy production.

Reactive Hypoglycemia and the Afternoon Crash

After a high-sugar or refined-carbohydrate meal, blood glucose rises rapidly and insulin is released to clear it from circulation. In some individuals, this response overshoots, causing blood sugar to fall too quickly—a phenomenon known as reactive hypoglycemia (11).

When glucose availability drops, the brain and nervous system perceive threat. Counter-regulatory hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline are released to raise blood sugar, often producing symptoms such as fatigue, shakiness, irritability, anxiety, and difficulty concentrating.

This cycle commonly explains the mid-afternoon crash, post-meal exhaustion, or the need for caffeine or sugar to “push through” the day.

Mitochondrial Strain and Impaired Cellular Energy

Beyond blood sugar fluctuations, chronic sugar exposure places strain on mitochondrial function. Mitochondria are responsible for converting nutrients into usable cellular energy. When glucose availability is erratic and insulin signaling is inefficient, mitochondrial output becomes less reliable (12,13).

Over time, cells struggle to meet energy demands despite adequate caloric intake. This contributes to persistent fatigue that does not resolve with rest, sleep, or increased caffeine consumption.

Fatigue in this context is not a motivation issue—it is a cellular energy regulation problem.

Why Caffeine Masks—Rather Than Fixes—Sugar-Driven Fatigue

Caffeine temporarily increases alertness by stimulating the nervous system and stress hormone release. While this can improve short-term focus, it does not correct the underlying metabolic instability driving fatigue (14).

In fact, reliance on caffeine in the presence of blood sugar dysregulation can further amplify cortisol output, deepen energy crashes later in the day, and perpetuate the cycle of stimulation followed by depletion.

Addressing sugar-driven fatigue requires restoring stable blood sugar signaling and mitochondrial efficiency—not overriding symptoms.

When energy production is regulated effectively, the need for constant stimulation diminishes, and resilience improves across physical, cognitive, and emotional domains (15).

→ Advanced Functional Lab Testing

The Impact of Added Sugar on Hormonal Regulation

Blood sugar regulation does not occur in isolation. It is tightly integrated with the endocrine system, meaning repeated sugar exposure influences far more than insulin alone. Over time, added sugar alters communication between metabolic, stress, appetite, and reproductive hormones—often in subtle ways that precede overt disease.

Cortisol, Stress Signaling, and Blood Sugar Volatility

When blood sugar rises and falls rapidly, the body relies on stress hormones—particularly cortisol—to restore balance. Cortisol increases glucose availability by signaling the liver to release stored sugar into the bloodstream (16).

With frequent sugar intake, this stress-response system becomes overutilized. Cortisol remains elevated more often and for longer durations, contributing to symptoms such as anxiety, sleep disruption, abdominal weight gain, and reduced stress tolerance.

Rather than reflecting psychological stress alone, elevated cortisol in this context often represents metabolic stress.

Insulin, Leptin, and Appetite Dysregulation

Insulin does more than regulate blood sugar—it also communicates with leptin, a hormone involved in satiety and energy balance. Chronic insulin elevation interferes with leptin signaling, reducing the brain’s ability to accurately sense fullness and energy sufficiency (17,18).

As leptin sensitivity declines:

Hunger increases despite adequate caloric intake

Cravings become more persistent

Weight regulation becomes more difficult

This hormonal mismatch helps explain why reducing calories without addressing sugar-driven signaling often backfires.

Thyroid and Sex Hormone Downstream Effects

Over time, metabolic and stress hormone disruption can influence thyroid signaling and sex hormone balance. Insulin resistance and chronic inflammation are associated with altered thyroid hormone conversion and reduced cellular responsiveness (19).

Similarly, elevated insulin levels affect ovarian and adrenal hormone production, contributing to cycle irregularity, PCOS features, and androgen imbalance in susceptible individuals (20).

These downstream effects highlight why sugar-related symptoms frequently extend beyond energy and weight, manifesting instead as complex, multi-system hormonal concerns.

Addressing hormonal imbalance in this context requires stabilizing metabolic inputs—not simply replacing hormones or suppressing symptoms.

Inflammation, Immune Activation, and Gut Dysregulation

Chronic exposure to added sugar does not only affect blood sugar and hormones—it also places sustained pressure on immune regulation and gut integrity. Over time, this contributes to low-grade inflammation that can amplify symptoms across multiple systems.

Sugar, Gut Permeability, and Microbiome Imbalance

Excess sugar alters the balance of gut microbes by preferentially feeding organisms that thrive on simple carbohydrates. This shift can reduce microbial diversity and increase production of inflammatory byproducts (21,22).

At the same time, repeated blood sugar spikes and inflammatory signaling weaken the intestinal barrier. When gut permeability increases, immune cells are exposed to compounds that would normally remain contained within the digestive tract.

This process does not always present as digestive symptoms. Many individuals experience fatigue, brain fog, skin issues, or joint pain without overt gastrointestinal distress.

Sugar, Dysbiosis, and Microbial Overgrowth

Chronic sugar exposure can shift the gut environment in ways that favor microbial imbalance. Excess simple carbohydrates preferentially feed certain bacteria and yeast, while repeated inflammatory signaling and blood sugar instability impair immune surveillance within the gut.

In this context, dysbiosis—including yeast overgrowth or other microbial imbalances—may develop as a secondary effect rather than a primary cause. These changes can further amplify inflammation, disrupt appetite and satiety signaling, and contribute to symptoms such as bloating, fatigue, brain fog, and persistent sugar cravings.

Importantly, sugar cravings alone do not indicate Candida or parasitic infection. However, when cravings occur alongside digestive symptoms, immune reactivity, or systemic inflammation, microbial imbalance may be one of several contributing factors reinforcing metabolic strain.

From a clinical standpoint, addressing gut imbalance without stabilizing blood sugar and inflammatory signaling often leads to incomplete or temporary improvement. Sustainable regulation requires correcting the metabolic environment that allowed dysbiosis to persist in the first place.

Low-Grade Inflammation and Immune Signaling

Inflammation associated with chronic sugar intake is often subtle and persistent rather than acute. Insulin resistance, oxidative stress, and gut-derived immune activation contribute to ongoing inflammatory signaling that the body must continuously regulate (23).

This low-grade inflammation increases overall physiological load, making recovery from stress, illness, or injury more difficult. It also interferes with hormone signaling, mitochondrial function, and nervous system regulation.

Over time, inflammatory burden compounds metabolic dysregulation rather than remaining a separate issue.

Why Symptoms Extend Beyond Digestion

Because immune and inflammatory signaling influences nearly every organ system, sugar-driven inflammation often presents as multi-system symptoms. These may include headaches, musculoskeletal pain, sleep disruption, mood changes, or heightened sensitivity to environmental stressors (24).

When inflammation is addressed only at the symptom level—without stabilizing metabolic inputs such as sugar exposure—improvement is often partial or short-lived.

Supporting gut integrity and immune balance requires reducing ongoing metabolic stressors while restoring regulatory capacity across systems (25).

Long-Term Metabolic Consequences of Chronic Sugar Intake

When added sugar exposure remains frequent over years rather than weeks or months, the cumulative effects extend beyond symptoms and into measurable metabolic disease risk. These outcomes are not sudden events—they reflect a gradual erosion of regulatory capacity across interconnected systems.

Metabolic Syndrome as a Spectrum, Not a Diagnosis

Metabolic syndrome is often described as a checklist of risk factors, but clinically it functions as a continuum. Blood sugar instability, rising insulin levels, central fat accumulation, lipid changes, and blood pressure shifts develop progressively rather than appearing all at once (26).

Many individuals move along this spectrum for years without meeting formal diagnostic criteria. During this time, fatigue, inflammation, hormonal disruption, and reduced stress tolerance often worsen—despite reassurance that labs are “acceptable.”

Understanding metabolic syndrome as a process rather than a label allows for earlier, more effective intervention.

Fatty Liver, Cardiovascular Risk, and Type 2 Diabetes

Excess sugar—particularly fructose—places a disproportionate burden on the liver. When glycogen storage capacity is exceeded, sugar is converted into fat, contributing to non-alcoholic fatty liver disease and impaired lipid metabolism (27,28).

These changes increase cardiovascular risk by promoting insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and vascular inflammation. Over time, pancreatic insulin output may no longer keep pace with demand, progressing toward type 2 diabetes (29).

Importantly, these conditions often share a common upstream driver: chronic metabolic stress from repeated sugar exposure.

Individual Susceptibility and Why Outcomes Vary

Not everyone responds to sugar in the same way. Genetics, early-life exposures, gut health, stress load, sleep quality, and activity patterns all influence metabolic resilience (30).

Some individuals develop disease quickly; others experience years of subclinical dysfunction before diagnosis. This variability explains why generalized dietary advice produces mixed results—and why personalized assessment is often necessary.

Reducing sugar intake alone may slow progression, but restoring metabolic health requires addressing the broader regulatory context in which sugar is consumed.

How to Identify Hidden Sources of Added Sugar

For many individuals, the primary challenge with sugar is not intentional overconsumption—it is unrecognized exposure. Added sugar is embedded throughout processed and packaged foods, often in products marketed as healthy, balanced, or functional.

Identifying these sources is a critical step in reducing metabolic strain without resorting to unnecessary restriction.

Misleading Health Foods and Label Pitfalls

Foods commonly perceived as “better choices” frequently contain significant amounts of added sugar. Yogurts, protein bars, granola, smoothies, plant-based milks, salad dressings, and sauces often include sweeteners to enhance palatability and shelf stability (31).

Marketing claims such as “natural,” “organic,” “low-fat,” or “plant-based” do not indicate low sugar content. In some cases, these products contain more added sugar than conventional alternatives.

Relying on front-of-package messaging rather than ingredient review is one of the most common reasons sugar intake remains higher than expected.

Understanding “Added Sugar” on Nutrition Panels

Nutrition labels now distinguish between total sugar and added sugar. Total sugar includes naturally occurring sugars from whole foods, while added sugar reflects sweeteners introduced during processing.

From a metabolic standpoint, added sugar is the more relevant metric. Frequent exposure—especially in liquid or refined form—places greater demand on insulin and stress-regulation systems than naturally occurring sugars consumed within whole foods (32).

Even small amounts can accumulate quickly when consumed across multiple meals and snacks.

Common Ingredient Aliases to Recognize

Added sugar may appear under many names, making it difficult to identify without familiarity. Common examples include cane sugar, evaporated cane juice, brown rice syrup, corn syrup, maltodextrin, agave, fruit juice concentrates, and various “natural flavors” with sweetening properties (33).

Becoming familiar with these aliases allows for more informed choices without rigid rules or excessive label scrutiny.

Reducing hidden sugar exposure is often less about eliminating foods entirely and more about strategic awareness—choosing products that minimize unnecessary metabolic load while preserving flexibility and enjoyment (34).

Reducing Sugar Without Triggering Restriction or Rebound

Reducing added sugar is most effective when approached as a regulatory strategy, not a rigid rule set. Aggressive elimination without supporting blood sugar stability often backfires, increasing cravings, stress hormone output, and rebound consumption.

Sustainable change focuses on improving metabolic signaling first—so the body no longer relies on sugar for short-term compensation.

Stabilizing Blood Sugar Before Cutting Sugar

When blood sugar is unstable, the drive for quick glucose is physiological, not psychological. Attempting to remove sugar without addressing this instability often intensifies fatigue, irritability, and cravings.

Stabilization begins with:

Adequate protein intake

Consistent meal timing

Sufficient dietary fat for satiety

Minimizing liquid sugars

These inputs reduce reactive hypoglycemia and lower the stress response associated with energy dips (35).

Once blood sugar is regulated, sugar cravings often decrease naturally—without force or restriction.

Protein, Fat, and Fiber as Regulatory Tools

Macronutrient balance plays a central role in reducing sugar dependence. Protein supports satiety and blood sugar control, fats slow gastric emptying, and fiber moderates glucose absorption while supporting gut health (36,37).

Rather than focusing on what must be removed, prioritizing these stabilizing nutrients improves metabolic flexibility and reduces reliance on rapid glucose spikes for energy.

This approach also preserves enjoyment and variety in the diet, which is critical for long-term adherence.

Why Sustainable Change Matters More Than Elimination

Short-term sugar elimination can reduce exposure, but without addressing regulation, benefits are often temporary. Metabolic systems adapt based on patterns, not isolated interventions.

Gradual reduction paired with improved signaling allows insulin sensitivity, appetite regulation, and energy production to normalize over time (38).

When the body no longer perceives sugar as a compensatory necessity, occasional intake becomes far less disruptive—and far less compelling.

A Root-Cause Approach to Blood Sugar and Metabolic Health

Persistent sugar sensitivity, energy instability, or hormonal symptoms are rarely caused by sugar intake alone. In clinical practice, these patterns often signal deeper regulatory strain involving insulin signaling, stress physiology, gut function, inflammation, and mitochondrial efficiency.

A root-cause approach focuses on identifying why the body has become reliant on frequent glucose input—and what systems are no longer communicating effectively.

When Sugar Sensitivity Signals Deeper Dysregulation

Heightened reactions to sugar—such as pronounced fatigue, anxiety, brain fog, or cravings—often reflect reduced metabolic flexibility. This may be influenced by factors such as chronic stress, disrupted sleep, inflammatory load, gut permeability, nutrient insufficiencies, or prior dieting patterns (39).

In these cases, simply “eating less sugar” may reduce exposure but does not restore regulation. Without addressing upstream contributors, symptoms often persist or resurface in other forms.

Recognizing sugar sensitivity as a signal, rather than a failure, allows for more targeted and sustainable intervention.

The Role of Functional Lab Testing

Functional lab testing can help clarify where regulation is breaking down. Markers related to insulin signaling, lipid metabolism, inflammation, adrenal stress patterns, gut integrity, and micronutrient status provide insight that standard screening labs may miss (40).

This information helps distinguish between:

Primary blood sugar dysregulation

Stress-driven metabolic instability

Gut-immune contributions

Mitochondrial energy limitations

Testing guides sequencing—ensuring interventions support the body rather than overwhelm it.

Individualized Strategies for Long-Term Regulation

Restoring metabolic health requires individualized planning based on physiology, lifestyle demands, and adaptive capacity. Strategies may include targeted nutrition adjustments, stress regulation, sleep optimization, gut support, and graduated metabolic conditioning.

When regulation improves, tolerance for dietary flexibility—including occasional sugar—often returns without triggering symptoms or setbacks.

A systems-based approach prioritizes resilience over restriction, allowing metabolic health to stabilize in a way that is both effective and sustainable (41).

When Sugar Sensitivity Reflects Underlying Metabolic Dysregulation

If fatigue, energy crashes, cravings, or hormonal symptoms persist despite eating “well” and doing all the right things, sugar may not be the root problem—but it is often a signal that metabolic regulation is under strain.

Addressing sugar-related symptoms effectively requires more than blanket restriction or willpower. It involves understanding how blood sugar signaling, stress physiology, gut health, inflammation, and cellular energy production are interacting in your body—and where regulation has begun to break down.

→ Metabolic & Hormone Health Optimization

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, evaluation is grounded in a root-cause, systems-based framework. Care focuses on identifying what is driving metabolic stress and supporting regulation in a way that is individualized, sustainable, and clinically appropriate.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sugar and Health

Is added sugar harmful even if my blood work looks normal?

Yes. Standard blood tests often reflect late-stage metabolic changes rather than early dysregulation. Added sugar can disrupt insulin signaling, blood glucose stability, and inflammatory pathways long before abnormalities appear on routine labs.

Can added sugar contribute to fatigue, brain fog, or mood swings?

Yes. Repeated blood sugar spikes and crashes affect energy availability, neurotransmitter balance, and stress hormone signaling. Over time, this can lead to unstable energy, cognitive fog, irritability, and reduced stress tolerance.

Why do I crave sugar even when I’m not physically hungry?

Sugar cravings are often driven by blood sugar instability, stress hormones, and reward signaling in the brain rather than true caloric need. These signals can override hunger cues, particularly during periods of fatigue or chronic stress.

Is sugar addiction real, or is it just a lack of willpower?

Cravings are not simply behavioral. Repeated sugar exposure reinforces neurochemical reward pathways and compensatory stress responses, making cravings feel urgent or compulsive even in highly disciplined individuals.

Are natural sugars like fruit or honey different from added sugar?

Sugars found in whole foods are accompanied by fiber, water, and micronutrients that slow absorption and moderate blood sugar responses. Added sugars are more concentrated and easier to overconsume, placing greater metabolic demand on regulatory systems.

Can sugar cravings mean Candida, dysbiosis, or gut infection?

Sometimes, but not always. Sugar cravings are most commonly driven by blood sugar instability and stress signaling. Gut imbalances may contribute in certain cases, particularly when digestive or immune symptoms are also present, but cravings alone are not diagnostic.

How long does it take to notice changes after reducing added sugar?

Some individuals notice improvements in energy or cravings within days to weeks, while deeper metabolic changes take longer. Responses vary based on insulin sensitivity, stress load, sleep quality, and overall nutrition.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Journal of Clinical Investigation – Mechanisms of insulin resistance and metabolic stress

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition – Added sugars and cardiometabolic risk

Obesity Reviews – Liquid calories, satiety signaling, and metabolic load

Nutrition Reviews – Sugar-sweetened beverages and metabolic outcomes

Endocrine Reviews – Early metabolic dysregulation before abnormal glucose markers

Diabetes Care – Pathophysiology of insulin resistance

Nature Reviews Endocrinology – Insulin signaling and metabolic disease progression

Physiological Reviews – Counter-regulatory hormones in glucose homeostasis

The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology – Hyperinsulinemia as an early metabolic driver

Journal of the American Medical Association – Limitations of fasting glucose and A1C

Clinical Endocrinology – Reactive hypoglycemia and autonomic symptoms

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Mitochondrial dysfunction in metabolic disease

Cell Metabolism – Nutrient signaling and mitochondrial efficiency

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Caffeine, cortisol, and stress physiology

Frontiers in Physiology – Energy regulation and metabolic resilience

Endocrine Reviews – Cortisol regulation and glucose metabolism

Nature Reviews Neuroscience – Insulin, leptin, and appetite signaling

Obesity – Leptin resistance and metabolic adaptation

Thyroid – Insulin resistance and thyroid hormone conversion

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Hyperinsulinemia and ovarian hormone signaling

Gut – Diet, sugar intake, and microbiome composition

Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology – Dysbiosis and intestinal permeability

Trends in Immunology – Metabolic inflammation and immune signaling

Brain, Behavior, and Immunity – Systemic inflammation and neurocognitive symptoms

Annual Review of Immunology – Immune regulation and chronic inflammatory load

Circulation – Metabolic syndrome as a progressive spectrum

Hepatology – Fructose metabolism and fatty liver disease

Journal of Hepatology – De novo lipogenesis and insulin resistance

Diabetologia – Progression from insulin resistance to type 2 diabetes

Nature Genetics – Genetic susceptibility to metabolic dysfunction

Public Health Nutrition – Hidden sugars in processed foods

Food & Nutrition Research – Added sugar labeling and metabolic relevance

Journal of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics – Sugar aliases in ingredient lists

Nutrition & Metabolism – Dietary patterns and metabolic load

American Journal of Physiology – Protein intake and glucose stability

Nutrients – Dietary fat, satiety, and glycemic control

Journal of Nutrition – Fiber intake and blood sugar regulation

Metabolism – Insulin sensitivity restoration through dietary modulation

Frontiers in Endocrinology – Stress, sleep, and metabolic regulation

Clinical Chemistry – Functional biomarkers in metabolic assessment

Systems Biology in Medicine – Integrative approaches to metabolic resilience