Mitochondrial Function: How Cellular Energy Shapes Aging, Metabolic Health, and Chronic Disease

Why mitochondrial health influences energy, resilience, and long-term health—and why symptoms appear long before disease is diagnosed

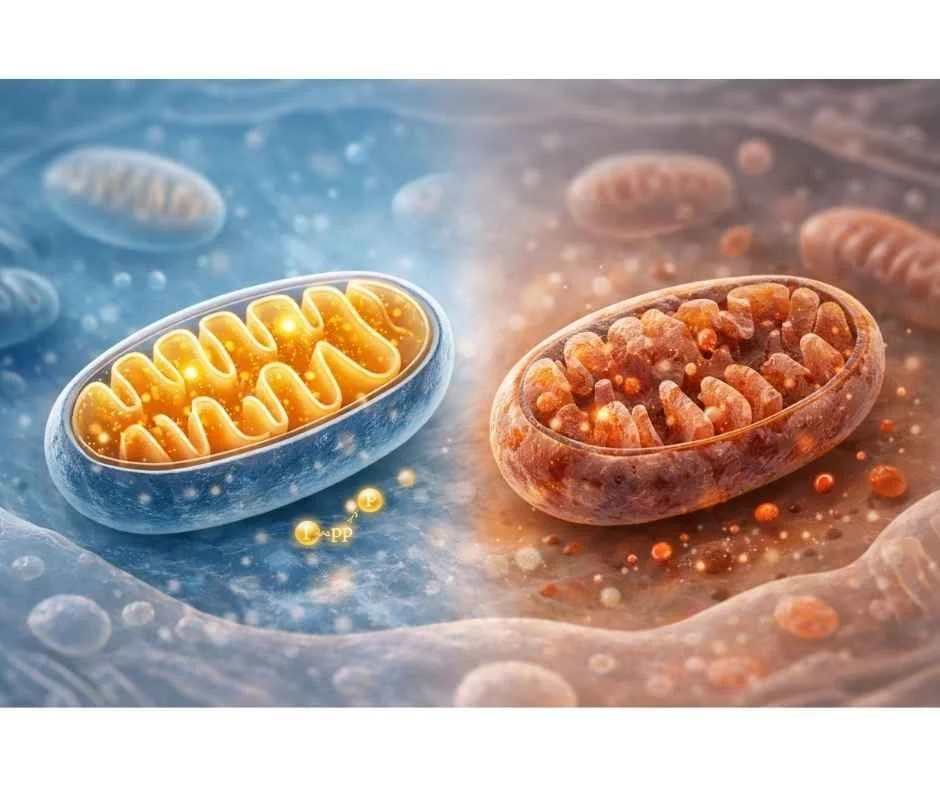

Persistent fatigue, declining resilience, and accelerated aging are often treated as lifestyle problems—or as inevitable consequences of getting older. In reality, these patterns frequently reflect a deeper biological constraint: reduced efficiency in cellular energy production.

Every function in the body depends on energy. Movement, cognition, hormone signaling, immune regulation, detoxification, and tissue repair all require a continuous supply of adenosine triphosphate, the body’s primary energy currency. ATP production occurs largely within mitochondria, specialized organelles present in nearly every cell (1).

When mitochondrial function declines, energy becomes limited at the cellular level. This does not always produce immediate disease, but it often shows up first as subtle, nonspecific symptoms. Over time, this loss of cellular efficiency contributes to chronic disease and accelerated biological aging (2,3).

Importantly, mitochondrial dysfunction is not a diagnosis and is rarely caused by a single factor. It represents a regulatory state influenced by cumulative stressors such as inflammation, oxidative stress, nutrient insufficiency, hormonal disruption, environmental toxins, infections, and chronic nervous system activation (4). These influences can impair mitochondrial signaling and energy output long before abnormalities appear on standard laboratory tests.

As research has advanced, mitochondria are no longer viewed simply as the powerhouses of the cell. They are now recognized as central regulators of metabolism, immune signaling, oxidative balance, and cellular repair. Their function helps determine how the body adapts to stress, how efficiently it ages, and how resilient it remains over time (5,6).

Understanding mitochondrial function provides a unifying framework for why symptoms that seem unrelated often occur together. Rather than chasing isolated symptoms, this perspective shifts the focus toward restoring cellular conditions that allow energy production and regulation to recover.

Why Energy Decline Is a Cellular Problem

Feeling persistently low on energy is often attributed to poor sleep, stress, aging, or lack of motivation. While these factors can contribute, they do not fully explain why many people remain fatigued despite adequate rest, nutrition, and lifestyle changes. In many cases, the limitation lies deeper—at the level of cellular energy production.

Energy is not created by effort or intent. It is generated inside cells through tightly regulated biochemical processes. When those processes become inefficient, the body must prioritize survival over performance, leading to reduced stamina, slower recovery, and diminished resilience even in the absence of overt disease (7).

Energy Availability Depends on Cellular Efficiency

Cells do not experience fatigue in the same way humans do. They respond to energy availability. When ATP production declines, cells shift resources away from nonessential tasks such as repair, detoxification, and adaptive responses to stress.

This helps explain why early energy decline often presents as:

Difficulty sustaining physical or mental effort

Poor tolerance to stress or exercise

Slower recovery after exertion

Increased sensitivity to temperature, fasting, or illness

These changes reflect energy conservation, not weakness or lack of discipline (8).

Why Rest and Stimulants Fail to Restore Energy

Sleep and rest are essential, but they do not directly repair impaired energy production. If mitochondrial signaling or substrate utilization is compromised, rest alone cannot normalize ATP output.

Stimulants such as caffeine temporarily increase alertness by activating the nervous system, but they do not increase cellular energy availability. Over time, reliance on stimulants can further tax already limited energy reserves by increasing demand without improving supply (9).

Energy Decline Often Appears Before Disease

One of the most challenging aspects of mitochondrial stress is that it often precedes diagnosable disease. Standard laboratory tests may appear normal because they measure static markers rather than dynamic energy production.

At this stage, the body is compensating. Energy is being rerouted toward essential functions, while optional processes such as optimal cognition, metabolic flexibility, and tissue repair are scaled back. This is why people may feel “off” for years before a clear diagnosis emerges (10).

Understanding energy decline as a cellular problem reframes fatigue and aging-related symptoms not as isolated complaints, but as early signals that regulatory capacity is being exceeded.

What Mitochondria Actually Do

Mitochondria are commonly described as the powerhouses of the cell, but this description is incomplete. Their role extends far beyond energy production. Mitochondria function as regulatory hubs that integrate nutrient availability, stress signals, immune activity, and metabolic demand to determine how cells adapt and survive (11).

ATP Production and Cellular Communication

The most recognized function of mitochondria is the production of adenosine triphosphate through oxidative phosphorylation. This process uses electrons derived from carbohydrates, fats, and proteins to drive ATP synthesis along the electron transport chain (12).

ATP, however, is not merely fuel. It acts as a signaling molecule that informs cells about energy availability and metabolic status. When ATP supply is sufficient, cells can invest resources in growth, repair, detoxification, and adaptation. When ATP becomes limited, cells shift toward conservation and survival mode (13).

This signaling role explains why declining mitochondrial efficiency affects multiple systems simultaneously rather than producing a single, isolated symptom.

Mitochondria as Metabolic Sensors

Mitochondria continuously sense changes in nutrient supply, oxygen availability, hormonal signals, and oxidative load. They adjust energy output accordingly, increasing or decreasing ATP production based on demand and environmental conditions (14).

Different tissues place different demands on mitochondrial function. The brain, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, and gastrointestinal tract are particularly energy dependent, which is why mitochondrial stress often presents as cognitive fog, exercise intolerance, metabolic instability, digestive dysfunction, or temperature dysregulation rather than uniform fatigue (15).

Regulation of Oxidative Balance

Mitochondria are also central regulators of oxidative balance. While they generate reactive oxygen species as a natural byproduct of energy production, these molecules serve signaling roles at controlled levels. Problems arise when oxidative demand exceeds antioxidant and repair capacity (16).

When this balance is disrupted, mitochondrial membranes, enzymes, and DNA become vulnerable to damage. Over time, this contributes to reduced efficiency, impaired signaling, and increased susceptibility to inflammation and chronic disease (17).

Mitochondria and Cellular Repair Pathways

Mitochondria influence cellular repair through processes such as autophagy and mitophagy, which help remove damaged cellular components and dysfunctional mitochondria. These pathways are essential for maintaining cellular health and metabolic flexibility over time (18).

When repair mechanisms slow—due to aging, nutrient deficiency, chronic stress, or toxin exposure—damaged components accumulate. This further compromises energy production and accelerates functional decline across tissues (19).

Understanding these roles clarifies why mitochondrial health cannot be reduced to energy levels alone. It shapes how cells communicate, repair, and adapt under both normal and stressful conditions.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Is a Regulatory State

Mitochondrial dysfunction is often misunderstood as permanent damage or an inherited defect. In reality, most people experiencing energy decline are dealing with a functional shift in regulation, not irreversible cellular failure. This distinction matters, because regulatory states can change when underlying pressures are reduced.

Cells continuously adjust energy production in response to their environment. When stressors accumulate—such as inflammation, nutrient insufficiency, hormonal disruption, toxin exposure, or chronic nervous system activation—mitochondria downregulate output to protect the cell. This adaptive response favors survival in the short term but reduces performance and resilience over time (20).

Why Dysfunction Develops Gradually

Mitochondrial stress rarely appears overnight. Instead, regulatory capacity erodes slowly as demands exceed repair and recovery. Early on, the body compensates by reallocating energy toward essential processes, while functions like optimal cognition, exercise tolerance, and metabolic flexibility are deprioritized (21).

Because compensation is effective for long periods, symptoms may remain subtle or fluctuate. This explains why people often feel “mostly fine” but notice increasing effort required to maintain normal function long before a clear diagnosis emerges.

Why Standard Labs Often Miss Mitochondrial Stress

Most routine laboratory tests measure static markers rather than dynamic energy production. Blood values may fall within reference ranges even when cellular efficiency is declining. As a result, people are frequently told nothing is wrong despite persistent fatigue, poor recovery, or reduced stress tolerance (22).

This disconnect can be frustrating and discouraging. Understanding mitochondrial dysfunction as a regulatory issue helps explain why symptoms are real even when conventional tests appear normal.

Regulation, Not Failure, Determines Outcomes

Viewing mitochondrial dysfunction through a regulatory lens shifts the clinical focus. Rather than asking how to force energy production, the more useful question becomes what factors are limiting regulation. Reducing interference—such as inflammation, oxidative burden, or metabolic overload—often allows energy production to recover without aggressive stimulation (23).

This perspective also explains why one-size-fits-all interventions frequently fail. Supporting mitochondrial health requires understanding the individual context in which energy regulation is occurring.

How Mitochondrial Stress Drives Aging and Chronic Disease

Aging is often described as a function of time, but biologically it reflects the gradual loss of cellular resilience. Mitochondria play a central role in this process because they sit at the intersection of energy production, repair capacity, and stress response.

When mitochondrial regulation is intact, cells adapt efficiently to metabolic demands and environmental stressors. When regulation falters, cells shift into conservation mode. Over time, this reduces the body’s ability to repair damage, maintain balance, and recover from everyday stress (24).

Oxidative Stress and Loss of Cellular Resilience

Mitochondria naturally generate reactive oxygen species as part of energy production. At controlled levels, these molecules act as signals that support adaptation and repair. Problems arise when oxidative demand exceeds antioxidant and repair capacity (25).

Excess oxidative stress damages mitochondrial membranes, enzymes, and genetic material. As this damage accumulates, energy production becomes less efficient, creating a cycle in which reduced ATP availability further limits repair. This cycle contributes to accelerated biological aging and increased vulnerability to chronic disease (26).

Inflammation and Energy Drain

Chronic inflammation places a significant energetic burden on the body. Immune activation requires substantial ATP, and prolonged inflammatory signaling diverts energy away from maintenance and repair processes.

Mitochondria both influence and respond to inflammatory signals. When inflammation becomes persistent, mitochondrial efficiency declines, which in turn amplifies inflammatory activity. This feedback loop helps explain why chronic inflammatory conditions are often accompanied by profound fatigue and poor recovery (27).

Tissue-Specific Decline and Disease Patterns

Not all tissues are affected equally by mitochondrial stress. Organs with high energy demands—such as the brain, heart, liver, skeletal muscle, and gastrointestinal tract—are often impacted first. This contributes to the wide range of conditions associated with mitochondrial dysfunction, including metabolic disorders, neurodegenerative diseases, immune dysregulation, and impaired detoxification (28).

These patterns highlight why aging and chronic disease rarely develop in isolation. They emerge from shared upstream constraints on cellular energy and regulation rather than from single-organ failure.

Environmental and Lifestyle Stressors That Disrupt Mitochondrial Function

Mitochondrial efficiency is shaped not only by genetics or aging, but by the cumulative environment in which cells operate. Modern life exposes mitochondria to a level of metabolic, chemical, and neurological stress that far exceeds what human physiology evolved to manage. Over time, this burden erodes regulatory capacity and limits energy production.

Environmental Toxins and Oxidative Burden

Mitochondria are particularly vulnerable to environmental toxins because of their role in energy metabolism and redox balance. Heavy metals, pesticides, air pollutants, and endocrine-disrupting chemicals interfere with mitochondrial enzymes, damage membranes, and increase oxidative stress (29).

Unlike acute toxic exposures, low-level chronic exposure often produces subtle effects that accumulate slowly. The result is not immediate illness, but reduced efficiency in ATP production, impaired repair mechanisms, and heightened inflammatory signaling. This helps explain why toxin burden is frequently associated with fatigue, metabolic instability, and poor stress tolerance rather than a single, clearly defined disease (30).

Sleep Disruption and Circadian Stress

Mitochondria operate on biological rhythms. Energy production, repair processes, and antioxidant defenses fluctuate across the day in response to circadian signaling. Disrupted sleep patterns, irregular light exposure, and chronic circadian misalignment impair these rhythms and reduce mitochondrial efficiency (31).

When circadian signals are inconsistent, mitochondria receive conflicting instructions about when to produce energy and when to prioritize repair. Over time, this mismatch contributes to persistent fatigue, hormonal disruption, and reduced resilience to both physical and psychological stress.

Chronic Stress and Nervous System Load

The nervous system plays a powerful role in regulating energy demand. Persistent sympathetic activation increases metabolic requirements while simultaneously impairing recovery and repair. In this state, mitochondria are asked to meet high demand without sufficient opportunity to restore balance (32).

This pattern is common in individuals experiencing long-term psychological stress, overtraining, chronic illness, or unresolved inflammatory conditions. Energy production may initially increase to compensate, but sustained demand eventually leads to depletion and dysregulation rather than improved performance.

Nutrient Availability and Metabolic Mismatch

Mitochondria require a steady supply of micronutrients to function efficiently. Deficiencies in minerals, B vitamins, amino acids, and antioxidants impair enzymatic reactions involved in energy production and repair (33).

At the same time, excessive caloric intake, frequent eating, or metabolic inflexibility can overload mitochondrial pathways. This mismatch—too much fuel with insufficient regulatory support—creates inefficiency rather than abundance, contributing to fatigue and metabolic dysfunction despite adequate or excessive nutrition (34).

Together, these stressors illustrate why mitochondrial dysfunction is rarely caused by a single factor. It emerges from the interaction between environmental load, lifestyle patterns, and the body’s capacity to regulate energy over time.

Why One-Size-Fits-All Energy Solutions Fail

When energy declines, the instinct is often to look for a single solution—change the diet, add supplements, increase exercise, or follow the latest longevity protocol. While these strategies may help some people temporarily, they often fail to produce lasting improvement because they do not account for individual differences in regulation and capacity.

Mitochondrial function is highly context dependent. The same intervention can support energy production in one person while increasing stress and depletion in another. Without understanding the underlying constraints on energy regulation, even well-intentioned approaches can backfire (35).

Diet, Fasting, and Metabolic Flexibility

Dietary strategies are frequently promoted as universal solutions for fatigue and aging. In reality, their effects depend on metabolic flexibility, nutrient status, stress load, and hormonal signaling.

For some individuals, reducing carbohydrate intake or extending fasting windows can improve mitochondrial efficiency and metabolic signaling. For others, these same approaches increase cortisol output, worsen sleep, impair thyroid signaling, or deepen energy deficits. When baseline resilience is low, additional metabolic stress may exceed adaptive capacity rather than strengthen it (36).

This variability explains why dietary advice often feels contradictory—and why outcomes differ so widely between individuals following similar plans.

Exercise as a Stressor or a Signal

Exercise is a powerful regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis and energy efficiency, but only when recovery capacity matches demand. When mitochondria are already under strain, excessive or poorly timed exercise can amplify inflammation and oxidative stress rather than improve energy production (37).

This is why some people feel energized by movement, while others experience worsening fatigue, prolonged soreness, or delayed recovery. The difference lies not in effort, but in the ability to adapt to the imposed load.

Supplements Cannot Override Systemic Overload

Supplements that support mitochondrial pathways are often marketed as direct energy boosters. While targeted nutrients can be helpful when deficiencies or increased demands exist, they do not correct the broader regulatory environment in which mitochondria operate.

If inflammation, toxin burden, sleep disruption, or nervous system stress remain unaddressed, supplements may offer limited or short-lived benefit. In some cases, they can even increase demand on already constrained systems (38).

Understanding why one-size-fits-all solutions fail reinforces the importance of context. Supporting mitochondrial health is not about applying more force, but about aligning interventions with the body’s current capacity to respond.

Supporting Mitochondrial Health Requires Systems-Level Assessment

By the time energy decline becomes noticeable, multiple regulatory systems are usually involved. Mitochondrial function does not exist in isolation; it reflects the combined influence of nutrient availability, inflammatory signaling, hormonal regulation, detoxification capacity, and nervous system balance. Because of this complexity, symptoms alone rarely provide enough information to determine what is limiting energy production.

Many people attempt to self-correct fatigue or aging-related symptoms by layering interventions—diet changes, supplements, exercise protocols—without understanding whether the body is capable of responding to those inputs. When regulatory capacity is already strained, additional stressors can deepen dysfunction rather than restore balance (39).

Why Symptoms Do Not Tell the Whole Story

Fatigue, poor recovery, and cognitive fog can arise from very different underlying patterns. In one person, mitochondrial stress may be driven primarily by micronutrient insufficiency. In another, chronic inflammation, toxin exposure, hormonal disruption, or circadian misalignment may be the dominant factor.

Because these drivers produce overlapping symptoms, treating based on presentation alone often leads to trial-and-error approaches with inconsistent results. A systems-level view shifts the focus from suppressing symptoms to identifying which inputs are limiting cellular energy regulation (40).

The Role of Functional Assessment

Evaluating mitochondrial health requires looking beyond routine blood work. Functional assessment can help reveal patterns such as impaired metabolic byproduct clearance, increased oxidative stress, nutrient insufficiencies, or disrupted energy pathways that are not visible on standard panels (41).

This type of assessment allows interventions to be selected based on need rather than trend. It also helps determine when supportive strategies are appropriate—and when the priority should be reducing physiological load before attempting to stimulate energy production.

→ Advanced Functional Lab Testing

Reducing Interference Before Forcing Energy

One of the most important clinical insights is that mitochondrial recovery often begins by removing obstacles rather than adding stimulation. Lowering inflammatory burden, improving sleep and circadian alignment, addressing toxin exposure, and restoring nervous system balance can allow energy production to normalize without aggressive intervention (42).

When support is introduced in the right context, mitochondria are far more responsive. This approach prioritizes resilience and sustainability over short-term energy spikes.

Aging Well Requires Reducing Interference

Aging is often framed as a process that must be fought or overridden. From a cellular perspective, however, aging reflects the gradual accumulation of interference—signals that disrupt energy production, repair, and regulation over time.

When mitochondrial function is supported, cells maintain the ability to adapt. They respond to stress efficiently, recover more quickly, and preserve balance across systems. When interference accumulates, energy is diverted toward survival rather than maintenance, and resilience declines even in the absence of overt disease (43).

Energy Returns When Regulation Improves

Sustained energy is not created by forcing output. It emerges when regulatory systems are no longer overwhelmed. Removing chronic stressors—whether inflammatory, metabolic, environmental, or neurological—reduces the demand placed on mitochondria and allows energy production to normalize.

This is why people often notice improvements in energy, clarity, and recovery not immediately after adding a new intervention, but after addressing factors that were silently draining capacity. Energy returns as regulation stabilizes, not as stimulation increases (44).

Resilience Over Stimulation

Short-term strategies that push energy output can mask underlying dysfunction, but they rarely restore long-term resilience. In contrast, approaches that support regulation prioritize durability. They allow the body to respond appropriately to both stress and rest, rather than remaining locked in a constant state of compensation.

From this perspective, aging well is less about doing more and more about creating conditions that allow cellular systems to function as intended. Mitochondria respond to consistency, recovery, and balance—not force (45).

This shift reframes aging as a modifiable process influenced by how well energy regulation is preserved over time.

A Personalized, Root-Cause Approach to Cellular Energy

Supporting mitochondrial health is not about applying the same protocol to everyone. Energy regulation reflects the combined influence of genetics, environment, nutrition, stress exposure, and recovery capacity. What restores balance for one person may overwhelm another if underlying constraints are not addressed first.

A root-cause approach begins by understanding why energy production has become limited. This includes identifying the stressors that are consuming regulatory capacity and determining whether the body is prepared to respond to support. In many cases, restoring energy is less about intensifying intervention and more about sequencing care appropriately.

When cellular systems are no longer operating under constant strain, mitochondria often regain efficiency without aggressive stimulation. Energy improves alongside resilience, recovery, and adaptability. This shift supports long-term health rather than short-lived gains.

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, care is guided by this systems-based perspective. Rather than chasing symptoms, the focus is on understanding the physiological context in which symptoms arise and addressing the factors that limit regulation over time.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Mitochondrial Function

What causes mitochondrial dysfunction?

Mitochondrial dysfunction develops when cumulative stressors overwhelm the cell’s ability to produce energy efficiently. Common contributors include chronic inflammation, oxidative stress, nutrient deficiencies, hormonal imbalances, environmental toxins, infections, and prolonged metabolic or nervous system stress.

Can mitochondrial dysfunction cause fatigue even if labs are normal?

Yes. Many standard labs do not assess cellular energy production or mitochondrial efficiency. It is common for people to experience significant fatigue, brain fog, or low resilience despite “normal” routine blood work when mitochondrial signaling and energy production are impaired.

Is mitochondrial dysfunction reversible?

In many cases, mitochondrial dysfunction is functional rather than permanent. When underlying stressors are identified and reduced, and cellular repair pathways are supported, mitochondrial efficiency and energy production can often improve over time.

How does aging affect mitochondrial function?

As we age, mitochondrial efficiency naturally declines due to accumulated oxidative stress, reduced repair capacity, and changes in metabolic signaling. This contributes to lower energy, slower recovery, and increased vulnerability to chronic disease, especially when compounded by environmental and lifestyle stressors.

Do supplements improve mitochondrial health?

Supplements can support mitochondrial function when deficiencies or increased demands are present, but they do not correct root causes on their own. Without addressing inflammation, toxin exposure, metabolic stress, or hormonal signaling, supplements alone rarely lead to sustained improvements in energy.

Why do energy-boosting strategies work for some people but not others?

Mitochondrial function is highly individualized. The same intervention can be supportive for one person and stressful for another depending on nutrient status, metabolic flexibility, nervous system regulation, and overall physiological load.

How long does it take to improve mitochondrial function?

Improvement depends on the severity and duration of stressors involved. Some people notice gradual changes in energy within weeks, while others require longer-term support as cellular repair and regulatory balance are restored.

When should mitochondrial dysfunction be evaluated clinically?

Clinical evaluation is appropriate when fatigue, poor recovery, cognitive fog, or declining resilience persist despite adequate sleep, nutrition, and lifestyle changes. Assessment helps identify whether deeper metabolic, inflammatory, or environmental factors are limiting cellular energy.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology – Mitochondria and cellular energy metabolism

Cell Metabolism – Mitochondrial function and aging-related decline

The Lancet – Mitochondrial dysfunction in chronic disease

Trends in Endocrinology & Metabolism – Hormonal and metabolic regulation of mitochondrial function

Science – Mitochondria as regulators of cellular signaling

Nature – Mitochondrial control of immune and metabolic homeostasis

Journal of Applied Physiology – Cellular energy availability and fatigue

Physiological Reviews – Energy conservation and adaptive stress responses

Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews – Stimulants, stress, and energy regulation

Clinical Chemistry – Limitations of standard laboratory testing in metabolic dysfunction

Annual Review of Biochemistry – Integrated roles of mitochondria beyond ATP production

Biochimica et Biophysica Acta – Oxidative phosphorylation and the electron transport chain

Cell – ATP as a signaling molecule in cellular regulation

Nature Metabolism – Mitochondria as metabolic sensors

Gut – Energy demand in gastrointestinal and metabolic tissues

Free Radical Biology & Medicine – Reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial signaling

Aging Cell – Oxidative damage and mitochondrial decline

Autophagy – Mitophagy and cellular repair mechanisms

Mechanisms of Ageing and Development – Accumulation of mitochondrial damage over time

Cellular Metabolism – Adaptive downregulation of mitochondrial output

Experimental Gerontology – Compensation and early energy decline

BMJ Open – Fatigue with normal laboratory findings

Frontiers in Physiology – Regulatory versus structural mitochondrial dysfunction

Nature Aging – Cellular resilience and aging biology

Redox Biology – Oxidative signaling and mitochondrial stress

Journal of Gerontology: Biological Sciences – Mitochondrial efficiency and aging

Immunology – Inflammation and energy demand

Lancet Neurology – Tissue-specific mitochondrial vulnerability

Environmental Health Perspectives – Environmental toxins and mitochondrial damage

Toxicological Sciences – Chronic low-level toxin exposure and cellular energy

Sleep Medicine Reviews – Circadian rhythm and mitochondrial function

Psychoneuroendocrinology – Stress, nervous system activation, and metabolic load

Nutrients – Micronutrient requirements for mitochondrial enzymes

Metabolism – Caloric excess, metabolic overload, and mitochondrial inefficiency

American Journal of Clinical Nutrition – Individual variability in metabolic interventions

Endocrine Reviews – Fasting, stress hormones, and metabolic adaptation

Sports Medicine – Exercise stress and mitochondrial recovery

Journal of Clinical Medicine – Limitations of supplement-based energy support

Functional Medicine Research – Systems-based approaches to fatigue

Systems Biology in Medicine – Symptom overlap and regulatory complexity

Clinical Biochemistry – Functional testing and metabolic assessment

Journal of Inflammation Research – Reducing physiological load to restore regulation

Aging Research Reviews – Interference, resilience, and biological aging

Frontiers in Aging – Recovery, regulation, and energy restoration

Nature Communications – Mitochondrial adaptability and long-term health