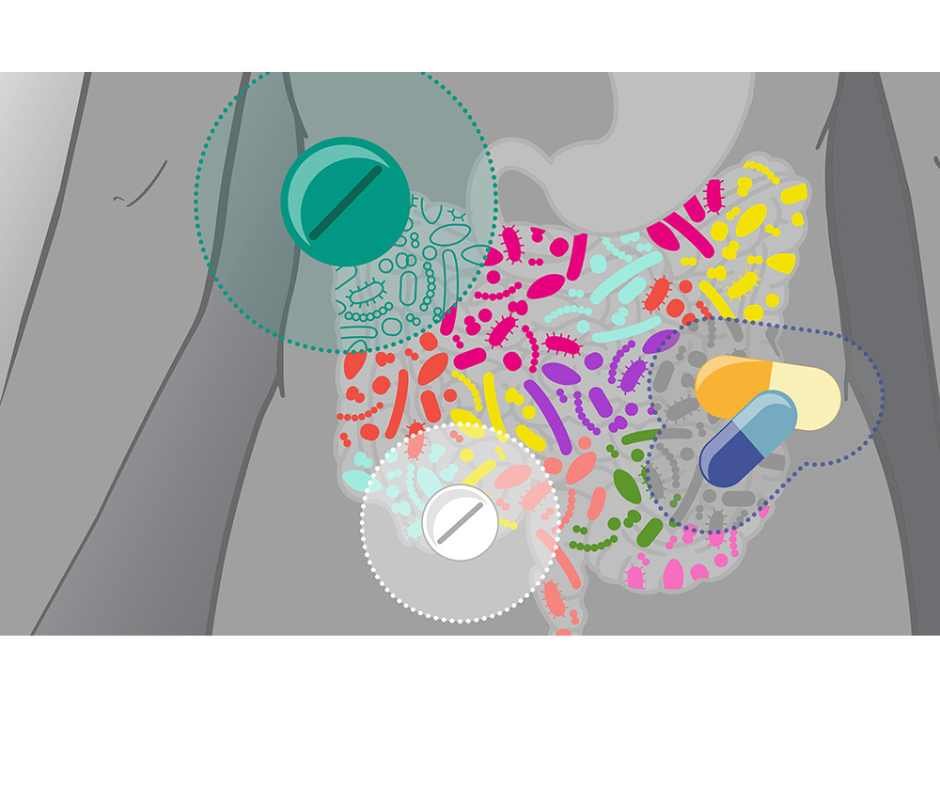

How PPIs, Antibiotics, Birth Control, and NSAIDs Disrupt Gut and Hormone Health

How PPIs, antibiotics, birth control, and NSAIDs damage gut integrity, deplete nutrients, and impair hormone metabolism

Your gut and hormone systems are central to how your body functions day to day. They regulate digestion, nutrient absorption, detoxification, metabolism, immune balance, mood, and fertility. When these systems are working well, the body feels stable and resilient.

But many commonly used medications quietly interfere with these core processes.

Acid blockers (PPIs), antibiotics, hormonal birth control, and NSAIDs are frequently prescribed—or taken over the counter—to manage reflux, infections, cycle symptoms, and pain. In the short term, they can be helpful. Over time, repeated or long-term use may weaken stomach acid production, disrupt the gut microbiome, impair nutrient absorption, and increase strain on detoxification pathways.

These changes rarely show up as dramatic side effects. Instead, they build gradually. Bloating, fatigue, anxiety, brain fog, acne, thyroid shifts, PMS, irregular cycles, or new food sensitivities may seem unrelated. In many cases, they reflect downstream effects of medications altering digestion, microbial balance, hormone metabolism, and immune signaling.

This article examines how proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), antibiotics, hormonal contraceptives, and NSAIDs disrupt gut health, hormone balance, and detox pathways—contributing to nutrient depletion, microbiome instability, and chronic inflammation—and outlines evidence-informed strategies to restore digestive integrity and metabolic resilience.

How PPIs, Antibiotics, Birth Control, and NSAIDs Deplete Nutrients and Damage Gut Health

Many prescription and over-the-counter medications do more than suppress symptoms—they alter digestion, stomach acid production, microbiome balance, and nutrient absorption. Over time, this interference can lead to clinically meaningful nutrient depletion, even in people consuming a nutrient-dense diet (1).

Unlike acute side effects, medication-induced deficiencies develop gradually. Low vitamin B12, magnesium, zinc, iron, folate, and fat-soluble vitamins may not produce immediate red flags. Instead, they show up as fatigue, anxiety, hormonal irregularity, immune vulnerability, impaired detoxification, or persistent digestive discomfort.

When digestion is disrupted, everything downstream is affected.

Stomach acid initiates protein breakdown, mineral absorption, and pathogen defense. The microbiome synthesizes key vitamins and regulates immune signaling. The gut lining governs what enters circulation and what remains contained. When medications interfere at any of these levels, nutrient status, hormone metabolism, and detox pathways begin to shift.

This is particularly true for acid-suppressing drugs, antibiotics, hormonal contraceptives, and NSAIDs—medications that directly influence stomach acid production, microbial diversity, mucosal integrity, and liver–gut detox communication.

Understanding how these drugs alter digestive physiology is essential to rebuilding nutrient sufficiency and restoring gut–hormone resilience.

Acid Blockers (PPIs & H2 Blockers) and Nutrient Depletion

Acid blockers such as proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) including Prilosec and Nexium, and H2 blockers like Pepcid, reduce stomach acid production to relieve reflux, ulcers, and indigestion.

Here’s the critical point:

Stomach acid is essential for protein breakdown, mineral absorption, microbial defense, and vitamin B12 activation through intrinsic factor.

When acid production is chronically suppressed, nutrient absorption progressively declines (2,3).

Common Nutrient and Metabolic Effects of Acid Blockers

Magnesium depletion

Vitamin B12 deficiency

Reduced iron absorption

Impaired calcium uptake

Lower zinc availability

Vitamin D insufficiency

Stomach acid initiates protein digestion and facilitates absorption of magnesium, iron, zinc, calcium, and vitamin B12. When acid levels decline, these processes become less efficient.

Magnesium depletion may impair cardiac rhythm stability and neuromuscular signaling (4). Reduced B12 absorption can lead to anemia, neuropathy, and cognitive changes if unrecognized.

Clinical Effects Associated with Acid Blocker–Related Nutrient Depletion

Persistent fatigue

Brain fog

Osteopenia or fractures

Iron-deficiency anemia

Neuropathy or tingling

Recurrent infections due to reduced gastric pathogen defense

These symptoms often develop gradually and are frequently misattributed to aging or stress rather than altered digestive physiology.

Supporting Physiological Resilience During Acid Blocker Therapy

Monitoring vitamin B12, magnesium, iron, and vitamin D

Replenishing deficiencies when indicated

Supporting mucosal integrity with zinc carnosine or DGL

Prioritizing mineral-rich whole foods

Encouraging fermented foods to maintain microbial balance

Addressing posture, breathing mechanics, and meal timing

These measures strengthen digestive resilience while therapy remains in place.

Can Acid Blockers Be Reduced?

Reflux often reflects upstream contributors such as dysbiosis, impaired motility, food sensitivities, stress physiology, or structural factors—not simply excess acid production.

When these drivers are corrected, reflux physiology often shifts.

As digestive regulation improves and inflammatory triggers are addressed, medication dependency may change under structured supervision.

The goal is not indefinite acid suppression.

The goal is restoring digestive strength and nutrient integrity.

Antibiotics and Gut Microbiome Disruption

Antibiotics are among the most frequently prescribed medications in modern healthcare. While they can be lifesaving in true bacterial emergencies, routine or repeated use often comes at a significant cost to the gut microbiome, immune resilience, and long-term metabolic stability.

Here’s the critical point:

Antibiotics do not distinguish between harmful pathogens and beneficial gut bacteria. In eliminating infection, they also disrupt microbial diversity—sometimes profoundly (5.6).

And recovery is not as simple as “just taking a probiotic.”

Research shows that antibiotic-induced microbiome disruption can persist for months, and in some cases years—especially after repeated courses or broad-spectrum agents (7). Certain keystone bacterial strains may not fully repopulate without targeted intervention.

This prolonged disruption affects:

Nutrient synthesis (B vitamins, vitamin K)

Immune regulation

Intestinal barrier integrity

Metabolic signaling

Neurotransmitter production

When microbial diversity remains suppressed, the downstream consequences can extend far beyond digestion—impacting inflammation, hormone metabolism, and even mood regulation.

Common Nutrient and Microbiome Effects of Antibiotics

Loss of beneficial gut flora

Reduced vitamin K production

Reduced B-vitamin synthesis

Impaired intestinal barrier integrity

Increased susceptibility to dysbiosis

Healthy gut bacteria synthesize vitamin K and several B vitamins essential for blood clotting, energy metabolism, and neurological function (8). When microbial diversity declines, nutrient synthesis, immune signaling, and mucosal defense are compromised.

Microbiome disruption can persist for months or even years, particularly after repeated or broad-spectrum antibiotic exposure (9).

Because recovery is not automatic, rebuilding the microbiome requires structured, layered support rather than a single supplement or short-term intervention.

Clinical Effects Associated with Antibiotic-Related Dysbiosis

Digestive distress (bloating, diarrhea, constipation)

Increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”)

Emerging food sensitivities

Recurrent infections

Candida overgrowth

Increased inflammatory load

Higher risk of asthma, allergies, and obesity (7)

Mood and cognitive changes via the gut–brain axis

These downstream effects are often misattributed to unrelated conditions rather than microbiome disruption.

Supporting Physiological Resilience During and After Antibiotic Therapy

Rebuilding the gut after antibiotic exposure requires intentional, phased support. Simply “waiting it out”—or relying on a single probiotic—often prolongs dysbiosis and increases the risk of persistent digestive, immune, and inflammatory dysfunction.

Spore-based probiotics during and after therapy

Saccharomyces boulardii to reduce antibiotic-associated diarrhea

Prebiotic fibers (onion, garlic, asparagus) to nourish commensal bacteria

L-glutamine and zinc carnosine to support barrier repair

Vitamin K–rich foods (leafy greens, natto)

B-complex support when clinically indicated

These strategies aim to restore microbial balance and intestinal integrity rather than passively waiting for recovery.

Nutrition and Lifestyle Strategies That Support Microbiome Recovery

Daily fermented foods (kefir, yogurt, kimchi, sauerkraut)

Low-sugar, anti-inflammatory dietary patterns

Bone broth or collagen to support mucosal repair

Adequate hydration

Sleep optimization

Gentle movement to restore motility and vagal tone

Microbiome recovery is influenced by terrain—stress, sleep, and inflammation matter as much as probiotics.

Can Recurrent Antibiotic Use Be Reduced?

Recurrent infections rarely occur in isolation.

When sinus infections, UTIs, bronchitis, or gut infections return repeatedly, the issue is often not simply bacterial exposure—but impaired host resilience.

Upstream drivers frequently include:

Nutrient depletion

Chronic stress physiology

Sleep disruption

Gut dysbiosis

Toxic load

Immune dysregulation

Impaired detoxification capacity

Repeated antibiotic exposure can temporarily suppress symptoms without correcting these underlying imbalances. Each course may further reduce microbial diversity, weaken mucosal immunity, and increase susceptibility to future infections.

This creates a cycle:

Infection → antibiotic → microbiome disruption → weakened immune defense → recurrent infection.

Breaking that cycle requires rebuilding—not repeated eradication.

Targeted herbal antimicrobials and terrain-based interventions can often address mild-to-moderate infections while preserving beneficial microbial populations. Unlike broad-spectrum antibiotics, many plant compounds exert selective antimicrobial pressure while supporting immune modulation and barrier integrity.

Pharmaceutical antibiotics remain essential in true medical emergencies such as sepsis, severe pneumonia, or confirmed resistant infections. In those settings, they are lifesaving.

However, routine or precautionary use for self-limiting or recurrent conditions frequently worsens long-term immune resilience.

As microbial diversity is restored, mucosal immunity strengthens, and nutrient deficiencies are corrected, infection susceptibility often declines—reducing reliance on repeated antibiotic courses under structured clinical supervision.

The goal is not simply to kill microbes.

The goal is restoring microbial balance and immune strength.

Hormonal Birth Control (Pills & Hormonal IUDs)

Hormonal contraceptives are commonly prescribed for cycle regulation, acne, PMS, or contraception. While often described as “balancing hormones,” their primary mechanism is suppression of ovulation and endogenous hormone production.

Synthetic estrogens and progestins signal to the brain that ovulation has already occurred. This reduces FSH and LH output, flattens natural hormone rhythms, and significantly lowers endogenous progesterone production. On comprehensive hormone testing, including DUTCH panels, ovarian hormone patterns are often markedly suppressed during use.

This suppression is intentional. The physiologic tradeoff is systemic.

Beyond reproductive signaling, hormonal contraceptives increase nutrient demand and measurable micronutrient depletion, alter gut microbial balance, and strain liver detoxification pathways responsible for hormone clearance (10).

Common Nutrient and Metabolic Effects of Hormonal Birth Control

Vitamin B6 depletion

Vitamin B12 depletion

Folate reduction

Magnesium depletion

Zinc depletion

Selenium reduction

Vitamin C depletion

Vitamin E depletion

These nutrients are required for:

Methylation and estrogen clearance

Neurotransmitter production (serotonin, dopamine, GABA)

Thyroid signaling

Antioxidant protection

Stress resilience

Immune function

When these nutrients decline, symptoms often appear gradually rather than immediately.

Clinical Effects Associated with Hormonal Contraceptive Use

Hormonal contraceptives rely on the liver for hormone metabolism and clearance. This process requires adequate B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, and antioxidant support.

At the same time, hormonal birth control can alter gut microbial balance. The gut microbiome plays a critical role in estrogen recycling and detoxification, and disruption of the estrobolome can increase estrogen recirculation rather than elimination (11).

Chronic nutrient depletion and altered hormone metabolism may contribute to:

PMS or PMDD

Low libido

Anxiety or depressive symptoms

Hair thinning or skin changes

Fatigue and reduced stress tolerance

Recurrent infections

Thyroid-related symptoms

Bloating and new food sensitivities

These patterns often develop gradually and may not be immediately connected to contraceptive use.

Supporting Physiologic Resilience During Hormonal Contraceptive Use

Support focuses on preserving nutrient sufficiency, protecting liver detox capacity, and maintaining gut integrity.

Common strategies include:

Replenishing B vitamins, magnesium, zinc, selenium, and antioxidants when indicated

Supporting estrogen metabolism with cruciferous vegetables and adequate fiber

Protecting gut barrier function and microbial diversity

Stabilizing blood sugar and stress physiology

Botanicals such as vitex, myo-inositol, and maca may support ovulatory signaling and luteal resilience during transition phases when used appropriately under supervision.

What Happens After Stopping Hormonal Birth Control?

When hormonal contraceptives are discontinued, the body must restart its own hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) signaling (12). During suppression, ovulation has been pharmacologically inhibited and endogenous progesterone production reduced. After discontinuation, the brain must resume pulsatile LH and FSH signaling, ovarian follicles must mature appropriately, ovulation must occur consistently, and progesterone must be produced in the luteal phase in order for true cycle stability to return.

This reactivation does not always occur immediately.

Common temporary changes after stopping hormonal birth control may include:

Irregular or delayed ovulation

Breakthrough bleeding or short cycles

Heavy or prolonged bleeding

Breast tenderness

Bloating

Migraines

Irritability

Intensified PMS

Mood variability

Acne or androgen shifts

Low progesterone symptoms

These patterns are not random. They reflect how well underlying regulatory systems are functioning.

During hormonal contraceptive use, endogenous estradiol and progesterone production are suppressed. On advanced hormone testing, this often appears as markedly flattened hormone curves. When suppression is removed, estrogen production frequently resumes before ovulation becomes consistent. This creates a common transition phase of relative estrogen dominance — where estrogen rises but progesterone remains insufficient due to inconsistent ovulation.

Estrogen production typically resumes before consistent ovulation is restored. This creates a common transition phase where:

Estrogen rises

Progesterone remains low due to inconsistent ovulation

Estrogen-dominant symptoms intensify

This does not indicate a new disorder. It reflects incomplete axis recovery.

At the same time, estrogen clearance must function efficiently. If liver detoxification pathways or gut microbial balance were impaired during contraceptive use, estrogen metabolites may recirculate — amplifying bloating, breast tenderness, headaches, and mood instability (11).

Hormonal contraceptives suppress symptoms, but they do not correct upstream drivers such as:

Insulin resistance

Chronic stress activation

Impaired estrogen clearance

Gut dysbiosis

Nutrient depletion (B6, B12, folate, magnesium, zinc, selenium)

Thyroid dysfunction

If these factors were present before starting birth control, they typically reemerge once suppression is removed.

Restoring physiologic hormone rhythm involves:

Repleting depleted nutrients required for ovulation and methylation

Supporting estrogen metabolism through liver and gut pathways

Rebuilding progesterone signaling via consistent ovulation

Stabilizing blood sugar and insulin dynamics

Reducing chronic sympathetic activation to normalize LH pulsatility

Discontinuation alone does not restore hormonal balance.

Rebuilding ovulatory signaling and endocrine coordination is what restores long-term stability.

The goal is not indefinite hormone suppression.

The goal is restoring endogenous hormonal regulation and metabolic balance.

NSAIDs (Ibuprofen, Naproxen, Aspirin) and Gut Barrier Disruption

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are widely used for headaches, joint pain, injuries, menstrual cramps, and fever. Because many are available over the counter, they are often perceived as low risk. Physiologically, however, repeated or long-term NSAID use directly alters prostaglandin signaling in ways that compromise gut integrity, nutrient absorption, and mucosal defense.

NSAIDs work by inhibiting cyclooxygenase (COX-1 and COX-2) enzymes, reducing prostaglandin production (13). While this reduces pain signaling, prostaglandins are also protective compounds required for maintaining the gastric mucus layer, supporting intestinal blood flow, regulating epithelial repair, and preserving barrier integrity.

When prostaglandin activity is chronically suppressed, the gastrointestinal lining becomes structurally more vulnerable.

How NSAIDs Weaken the Gut Lining

COX-1 inhibition decreases protective prostaglandins that maintain mucosal blood flow, mucus secretion, and epithelial regeneration (14). With repeated exposure, microinjury accumulates across the stomach and small intestine.

This does not always present as an acute ulcer. More commonly, it manifests as:

Subtle erosion of the mucosal barrier

Increased intestinal permeability

Low-grade inflammatory activation

Impaired epithelial repair

When barrier integrity weakens, bacterial fragments, endotoxins, and partially digested proteins can translocate into circulation. The immune system responds with inflammatory signaling.

Over time, this low-grade immune activation increases systemic inflammatory tone.

Common Nutrient and Metabolic Effects of NSAIDs

Folate depletion

Vitamin C depletion

Iron depletion (via microbleeding and impaired absorption)

Potassium imbalance

Reduced gastric mucosal protection

Increased intestinal permeability

Microbiome disruption

Chronic microbleeding may gradually lower iron stores (16). Reduced vitamin C impairs collagen repair and antioxidant buffering. Folate depletion may affect cellular regeneration and methylation pathways.

These changes rarely produce immediate symptoms. Instead, they accumulate gradually, affecting energy production, immune regulation, and tissue resilience.

Clinical Effects Associated with NSAID-Related Gut Injury

Reflux, gastritis, ulcer formation, or GI bleeding

Fatigue and reduced stamina

Increased intestinal permeability (“leaky gut”) and mucosal injury (15)

Iron-deficiency anemia (16)

Food sensitivities and immune activation

Kidney strain and electrolyte imbalance (17)

When intestinal permeability increases, immune reactivity becomes more pronounced. Cytokine signaling rises. Inflammatory tone shifts upward.

Rather than resolving inflammation, chronic NSAID exposure may perpetuate a gut-driven inflammatory loop.

When gut barrier integrity declines, immune activation increases and systemic inflammatory tone rises. This heightened inflammatory signaling often presents as:

Worsening joint pain

Headaches

Musculoskeletal stiffness

Autoimmune flares

As symptoms intensify, NSAIDs are taken again. Pain temporarily decreases, but mucosal injury and intestinal permeability continue to progress beneath the surface.

Over time, this creates a self-perpetuating loop:

Pain → NSAID → mucosal damage → intestinal permeability → immune activation → systemic inflammation → more pain.

What begins as short-term pain control can gradually become a driver of chronic inflammatory burden through compromised gut integrity.

This distinction prevents symptom suppression from evolving into long-term physiologic compromise.

NSAIDs and the Gut–Hormone Axis

The gut microbiome and intestinal barrier play a critical role in estrogen metabolism and detoxification. When mucosal integrity is compromised, hormone clearance patterns may shift.

Impaired barrier function can:

Increase systemic inflammatory signaling

Alter microbial diversity

Influence estrogen recirculation through the gut–liver axis

Over time, these changes may contribute to bloating, cycle irregularity, PMS intensification, or inflammatory flares in susceptible patients.

The issue is not short-term, clinically appropriate NSAID use. The concern arises with repeated, long-term exposure that gradually weakens barrier resilience and nutrient sufficiency.

Supporting Physiological Resilience During NSAID Therapy

When NSAIDs are clinically necessary, protective strategies can help reduce gut barrier injury and inflammatory escalation.

Supportive measures may include:

Zinc carnosine to reinforce gastric mucosal defense

L-glutamine to support intestinal epithelial repair

Vitamin C to assist collagen synthesis and antioxidant buffering

Omega-3 fatty acids to modulate inflammatory cytokine signaling

Curcumin or boswellia to influence inflammatory pathways without gut erosion

Adequate hydration and mineral balance

Anti-inflammatory dietary patterns rich in polyphenols and phytonutrients

These strategies aim to preserve gut integrity and reduce downstream immune activation while therapy remains in use.

The Long-Term Objective

NSAIDs are clinically appropriate in acute, clearly inflammatory states.

The long-term objective is not continuous prostaglandin suppression.

The objective is restoring gut integrity, reducing inflammatory burden at the barrier level, and rebuilding nutrient sufficiency so immune and hormone regulation can stabilize naturally.

Reassessing Chronic NSAID Dependence

Persistent reliance on NSAIDs often reflects unresolved upstream drivers of inflammation — particularly gut barrier dysfunction and metabolic instability — rather than isolated pain pathology.

Common contributors include:

Gut dysbiosis and intestinal permeability

Insulin resistance

Chronic stress physiology

Poor sleep quality

Micronutrient depletion

Mechanical instability or connective tissue weakness

When gut integrity is restored, inflammatory signaling becomes more regulated.

When metabolic flexibility improves, cytokine activity stabilizes.

When nutrient sufficiency returns, tissue resilience improves.

NSAIDs remain clinically appropriate in acute, clearly inflammatory states where short-term prostaglandin suppression reduces severe pain or tissue stress.

The long-term objective, however, is not continuous suppression.

The objective is restoring gut integrity, reducing inflammatory burden at its source, and rebuilding physiologic resilience.

This is the difference between suppressing inflammation and resolving it.

While NSAIDs primarily compromise health through gut injury, prostaglandin suppression, and nutrient depletion, they are only one part of a broader pain-medication landscape.

Other commonly used pain medications — including acetaminophen, steroids, and opioids — exert harm through distinct biochemical pathways, including oxidative stress, immune suppression, and impaired detoxification.

→ When Pain Relief Backfires: The Hidden Risks of Tylenol, NSAIDs, Steroids & Opioids

What You Can Do Now: Restore Gut and Hormone Physiology at the Root

PPIs, antibiotics, hormonal contraceptives, and NSAIDs are designed to suppress symptoms. They are not designed to restore stomach acid production, rebuild the microbiome, repair the gut lining, or normalize hormone signaling.

When nutrient depletion, microbiome disruption, or hormone suppression accumulates, symptoms often persist despite “normal” labs.

Restoration requires correcting what has been disrupted and removing what continues to drive dysfunction.

1) Remove or Reduce the Ongoing Driver (When Clinically Appropriate)

If a medication is actively impairing digestion, microbial balance, hormone signaling, or mucosal integrity, rebuilding will be limited while the disruption continues.

The first step is structured reassessment.

This may include:

Reviewing why the medication was started

Determining whether the original condition still requires it

Evaluating duration of use versus intended short-term indication

Identifying safer alternatives when appropriate

Implementing a gradual, supervised taper when clinically indicated

Some medications are essential in specific clinical situations. Others were intended for short-term use but continue indefinitely without structured reassessment.

Physiology normalizes when the underlying drivers are addressed and unnecessary suppression is reduced under proper medical oversight.

Rebuilding does not begin with supplements.

It begins with removing what is perpetuating drivers.

2) Rebuild the Microbiome

Microbial diversity regulates digestion, immune balance, estrogen metabolism, neurotransmitter production, and inflammatory tone.

Restoration may include:

Targeted probiotic therapy based on clinical context

Strategic use of Saccharomyces boulardii after antibiotics

Prebiotic fibers to nourish commensal bacteria

Daily fermented foods when tolerated

Reduction of excess sugar and alcohol

Microbiome repair is not immediate. Repeated antibiotic exposure or long-term acid suppression may require months of intentional rebuilding.

3) Replete What Has Been Depleted

Different medication classes predictably alter nutrient status.

Repletion is targeted, not generic.

Common patterns include:

PPIs / H2 blockers

→ Vitamin B12, magnesium, zinc, iron, vitamin D

Antibiotics

→ Microbial diversity, vitamin K synthesis, B vitamins

Hormonal contraceptives

→ Vitamin B6, B12, folate, magnesium, zinc, selenium, vitamins C and E

NSAIDs

→ Folate, iron, vitamin C, potassium (as clinically indicated)

Correction is guided by laboratory assessment and symptom correlation, not guesswork.

Nutrient sufficiency restores enzymatic function, mitochondrial efficiency, immune regulation, and hormone metabolism.

4) Repair and Protect the Gut Lining

Chronic acid suppression, antibiotics, and NSAIDs weaken mucosal integrity and increase intestinal permeability.

Repair strategies may include:

L-glutamine to support enterocyte regeneration

Zinc carnosine to stabilize gastric and intestinal mucosa

Collagen or bone broth to support structural repair

DGL and aloe to soothe irritated tissue

Sulforaphane or NAC to reduce oxidative stress

When barrier integrity improves, systemic inflammation declines.

5) Restore Regulatory Physiology

Symptom suppression bypasses regulation. Recovery restores it.

This includes:

Stabilizing blood sugar and insulin signaling

Rebuilding ovulatory function after hormonal suppression

Supporting estrogen clearance through the gut–liver axis

Restoring circadian rhythm and sleep quality

Reducing chronic stress activation

As regulatory systems normalize, inflammatory signaling quiets, hormone patterns stabilize, and tissue repair capacity improves.

Resilience returns through restoration — not suppression.

Restoring Gut Health and Hormone Balance After Long-Term Medication Use

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, recovery begins by identifying medication-related disruption and correcting the physiologic imbalances that follow.

Persistent reflux, bloating, fatigue, PMS, acne, mood instability, irregular cycles, or chronic inflammatory symptoms that emerge during or after prolonged medication use often reflect:

Impaired digestion and low stomach acid physiology

Microbiome imbalance and reduced microbial diversity

Micronutrient depletion

Altered estrogen metabolism

Compromised detoxification pathways

These patterns do not resolve with additional suppression. They require objective assessment.

Comprehensive evaluation clarifies:

Intracellular micronutrient status

Gut microbial balance and inflammatory markers

Estrogen metabolism and clearance patterns

Methylation and detoxification capacity

Precise testing allows for targeted restoration of gut integrity, hormone regulation, and metabolic resilience — rather than continued symptom management.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

Frequently Asked Questions About Medication Side Effects on Gut Health, Hormones, and Nutrient Depletion

Do PPIs and acid blockers cause nutrient deficiencies?

Yes. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and H2 blockers reduce stomach acid, which is required for proper absorption of vitamin B12, magnesium, zinc, calcium, iron, and vitamin D. Long-term acid suppression can impair mineral ionization, intrinsic factor activation, and protein digestion, increasing the risk of nutrient depletion over time.

What nutrients do PPIs and H2 blockers deplete?

Commonly affected nutrients include:

Vitamin B12

Magnesium

Zinc

Iron

Calcium

Vitamin D

Because stomach acid initiates digestion and supports mineral absorption, prolonged suppression disrupts multiple downstream pathways simultaneously.

Can long-term acid blockers cause low magnesium symptoms?

Yes. Chronic PPI use has been associated with hypomagnesemia. Low magnesium may present as muscle cramps, heart palpitations, arrhythmias, fatigue, anxiety, tremors, or neurological symptoms. Severe depletion can affect cardiac rhythm stability.

Can PPIs cause vitamin B12 deficiency and nerve symptoms?

Yes. Vitamin B12 absorption requires adequate stomach acid and intrinsic factor. Long-term acid suppression can impair this process. Untreated B12 deficiency may contribute to anemia, neuropathy, numbness or tingling, memory changes, cognitive decline, and mood instability.

Do antibiotics damage the gut microbiome long term?

Antibiotics do not distinguish between harmful pathogens and beneficial gut bacteria. Broad-spectrum agents can significantly reduce microbial diversity. In some cases, microbiome disruption persists for months or longer, particularly with repeated courses.

Loss of microbial diversity affects immune regulation, nutrient synthesis, intestinal barrier integrity, and inflammation control.

How long does it take the gut microbiome to recover after antibiotics?

Recovery timelines vary. Partial microbial restoration may occur within weeks, but full ecosystem recovery can take months and, in some cases, longer—especially after repeated antibiotic exposure or in the presence of ongoing stress, poor diet, or gut dysfunction.

Simply taking a probiotic is rarely sufficient. Rebuilding requires microbial diversity, mucosal repair, and metabolic support.

Can antibiotics cause yeast overgrowth or Candida?

Yes. When beneficial bacteria are reduced, opportunistic organisms such as Candida species may proliferate. This imbalance can contribute to bloating, brain fog, fatigue, recurrent infections, skin issues, and immune dysregulation.

Does hormonal birth control deplete vitamins and minerals?

Hormonal contraceptives have been associated with depletion of:

Vitamin B6

Vitamin B12

Folate

Magnesium

Zinc

Selenium

Vitamin C

Vitamin E

These nutrients are required for liver detoxification, neurotransmitter production, hormone metabolism, and oxidative stress regulation.

Is breakthrough bleeding on birth control a real period?

No. Withdrawal or breakthrough bleeding on hormonal birth control is not a true menstrual period. It reflects a drop in synthetic hormone exposure rather than a completed ovulatory cycle.

Ovulation is typically suppressed, and endogenous progesterone is not produced in meaningful amounts.

Can hormonal birth control suppress natural hormone production?

Yes. Hormonal contraceptives suppress the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian (HPO) axis. Ovulation is inhibited, and endogenous estrogen and progesterone production are reduced. On hormone testing such as DUTCH panels, hormone metabolites often appear significantly suppressed during active use.

Can hormonal birth control affect gut health and estrogen clearance?

Yes. Hormonal contraceptives influence the gut–liver axis. They can alter microbial composition, increase oxidative stress, and impact estrogen metabolism. Disruption of the estrobolome may impair hormone clearance and contribute to PMS, mood symptoms, and cycle instability after discontinuation.

Can NSAIDs cause leaky gut or damage the gut lining?

Yes. NSAIDs inhibit prostaglandins that protect the gastrointestinal lining. Repeated use increases intestinal permeability, impairs mucosal defense, and can contribute to ulcers, bleeding, food sensitivities, and chronic inflammatory signaling.

What nutrients do NSAIDs deplete?

NSAID use has been associated with depletion or disruption of:

Folate

Vitamin C

Iron

Potassium

They may also impair collagen repair and mucosal integrity.

What are the signs a medication may be affecting gut or hormone health?

Common patterns include:

Persistent bloating or reflux

New food sensitivities

Chronic fatigue

Mood changes or anxiety

Irregular cycles or intensified PMS

Brain fog

Slow recovery from stress or illness

Worsening inflammatory symptoms

When symptoms develop after starting or increasing a medication, structured evaluation is warranted.

Can PPIs, NSAIDs, or hormonal contraceptives be tapered safely?

Some medications can be tapered under medical supervision when clinically appropriate. Abrupt discontinuation—particularly with PPIs or hormonal contraceptives—may trigger rebound acid production or temporary cycle disruption.

Safe transition requires correcting nutrient depletion, supporting gut repair, stabilizing blood sugar, and restoring physiologic signaling.

What tests can identify medication-related nutrient depletion or gut damage?

Comprehensive evaluation may include:

Micronutrient panels

Vitamin D and B-vitamin assessment

Iron studies

Magnesium status

Stool testing for microbiome diversity and inflammation

Hormone metabolite testing

Markers of intestinal permeability and detoxification capacity

Objective testing allows for targeted correction rather than symptom suppression.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Nutrients – Evidence of Drug–Nutrient Interactions with Chronic Use of Commonly Prescribed Medications

Therapeutic Advances in Drug Safety – Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk of Vitamin and Mineral Deficiency: Evidence and Clinical Implications

Current Gastroenterology Reports – The Risks of Long-Term Proton Pump Inhibitor Use

FDA Drug Safety Communication – Low Magnesium Levels Can Be Associated with Long-Term Use of Proton Pump Inhibitor Drugs (PPIs)

Journal of Clinical Medicine – Effects of Antibiotics on the Gut Microbiome: A Review of the Literature

Microorganisms – Antibiotics as Major Disruptors of Gut Microbiota

Frontiers in Microbiology – Antibiotic-Associated Dysbiosis and Approaches for Its Management

Case Reports in Medicine – Association of Broad-Spectrum Antibiotic Therapy and Vitamin K Deficiency-Induced Coagulopathy

Frontiers in Microbiology – Long-Term Ecological Impacts of Antibiotic Exposure on the Human Gut Microbiota

The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition – Oral Contraceptives and Changes in Nutritional Requirements

Gut Microbes – The Estrobolome and Estrogen Metabolism in Health and Disease

Endocrine Reviews – Hormonal Contraception and Suppression of the Hypothalamic–Pituitary–Ovarian Axis

Nature Reviews Drug Discovery – The Structural Basis for NSAID Inhibition of Cyclooxygenase

Gastroenterology – Mechanisms of NSAID-Induced Gastrointestinal Injury

Gut – Intestinal Permeability and Inflammation Associated with NSAID Use

Gastroenterology – NSAID-Induced Small Intestinal Injury and Iron Deficiency

Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology – Kidney Injury Associated with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs

Circulation – Cardiovascular Risks Associated with Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs