Hidden Toxins and Toxic Burden: How Environmental Toxin Exposure Disrupts Hormones, Thyroid Function, and Chronic Disease

How cumulative toxic exposure disrupts regulatory systems—and why hormones, thyroid function, and chronic illness are often the first to be affected

Modern chronic illness is increasingly shaped not by a single diagnosis, but by cumulative physiological strain.

One of the most significant—and least adequately addressed—contributors to that strain is chronic, low-dose toxic exposure from food, drinking water, household products, and the built environment. These exposures rarely cause immediate illness. Instead, they accumulate quietly over years, interacting with nutrition status, stress physiology, gut health, and detoxification capacity to alter how core regulatory systems function (1).

Hormonal signaling, thyroid regulation, immune balance, and cellular energy production are particularly vulnerable to this type of exposure. Disruption often occurs without dramatic lab abnormalities, which is why symptoms such as fatigue, weight resistance, mood instability, poor stress tolerance, and inflammatory conditions are frequently labeled as idiopathic or age-related rather than environmentally driven.

This article provides a clinical overview of toxic burden: how modern exposures enter the body, how they interfere with hormonal and metabolic regulation, why thyroid dysfunction and chronic illness so often emerge downstream, and how different categories of toxins fit together within a systems-based medical framework.

What Is Toxic Burden? How Low-Dose Environmental Toxin Exposure Builds Over Time

Toxic burden refers to the cumulative load of environmental toxins the body must process through detoxification pathways. When exposure exceeds clearance capacity, regulatory systems—including hormones, thyroid signaling, immune balance, and mitochondrial energy production—begin to shift. This often presents as fatigue, hormone resistance, thyroid symptoms, and chronic inflammation despite normal laboratory testing.

This balance is not theoretical—it is physiological. Every day, the body must respond to chemical inputs from food, water, air, and direct skin contact. What determines whether those exposures remain tolerable or become disruptive is not just what the exposure is, but how much arrives, how often, and how resilient the underlying detox systems are.

Several variables shape toxic burden simultaneously:

The number of exposures

Modern life rarely involves a single toxin. Instead, individuals are exposed to dozens of compounds daily—often from multiple sources at once.The frequency and chronicity of exposure

Low-dose exposure repeated day after day places far more strain on regulatory systems than an isolated, short-term exposure.The route of exposure

Chemicals absorbed through the lungs or skin enter circulation directly, bypassing first-pass liver detoxification and placing immediate demand on systemic clearance pathways.The body’s detoxification and repair capacity

Detoxification depends on adequate nutrition, gut integrity, bile flow, kidney function, lymphatic movement, mitochondrial energy production, and antioxidant buffering. When any of these are compromised, tolerance to chemical exposure drops.

This is why modern toxin exposure is rarely acute. It is cumulative, low-dose, and relentless—and why symptoms often appear gradually rather than dramatically (2).

Clinically, this matters because detoxification is not automatic. It is an energy-intensive, nutrient-dependent, multi-organ process involving coordinated activity of the liver, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, lymphatic system, immune signaling, and mitochondria. When incoming chemical load consistently exceeds what these systems can handle, the body adapts by shifting function—often subtly at first (3).

Over time, these adaptations can manifest as hormonal resistance, impaired thyroid signaling, chronic inflammation, reduced stress tolerance, and declining cellular energy—long before overt disease or abnormal standard labs appear.

Why Modern Environmental Toxins Disrupt Hormones, Metabolism, and Detox Pathways

Human detoxification systems evolved to handle intermittent exposure to naturally occurring toxins—plant compounds, smoke, microbial byproducts, and occasional environmental stressors. These exposures were typically limited in duration, variable in intensity, and followed by recovery periods that allowed detox and repair systems to recalibrate.

Modern chemical exposure is fundamentally different. It challenges human physiology in ways our regulatory systems were never designed to manage, particularly in three interrelated dimensions.

1. Chronic Daily Toxin Exposure Without Detox Recovery

Unlike historical toxin exposure, modern synthetic chemicals are encountered continuously. They enter the body daily through food packaging, drinking water, indoor air, textiles, furniture, cleaning agents, and personal care products. This means detoxification pathways are rarely given a true recovery window (4).

From a physiological standpoint, this matters because detoxification is not a passive process. It requires energy, enzymatic activity, antioxidant buffering, and coordinated organ function. When exposure is constant, detox pathways operate in a near-permanent state of demand. Over time, this contributes to nutrient depletion, oxidative stress, and reduced metabolic flexibility—lowering the threshold at which symptoms begin to appear.

2. Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) and Hormone Signaling Interference

Many modern environmental chemicals do not behave like classic toxins that simply damage cells. Instead, they act as endocrine disruptors, meaning they resemble natural hormones closely enough to interfere with hormonal signaling (5).

These compounds can bind to estrogen, thyroid, cortisol, insulin, and other hormone receptors—sometimes activating them weakly, sometimes blocking them, and sometimes distorting normal feedback loops altogether. The result is not necessarily a deficiency or excess of hormone in the bloodstream, but impaired communication at the tissue level.

Clinically, this explains why patients may have “normal” hormone or thyroid labs while still experiencing symptoms such as fatigue, weight resistance, mood instability, cycle irregularities, or cold intolerance. The issue is not always hormone quantity—it is signal fidelity.

3. Bioaccumulation: Why Toxins Build Up in Fat and Endocrine Organs

Many synthetic chemicals are fat-soluble and resistant to breakdown. Rather than being eliminated quickly, they are sequestered in adipose tissue, the brain, and endocrine organs, where they can persist for years (6).

This storage mechanism is protective in the short term, but it creates delayed and nonlinear symptom patterns. Symptoms often intensify during periods when stored toxins are mobilized—such as hormonal transitions, chronic stress, illness, fasting, weight loss, or increased metabolic demand.

This is why toxin-related symptoms can seem to “appear out of nowhere,” worsen during lifestyle changes intended to improve health, or fluctuate unpredictably. The exposure did not suddenly occur—the physiological burden crossed a threshold.

One of the most clinically significant ways toxins exert these effects is through endocrine-disrupting mechanisms.

How Environmental Toxins Disrupt Hormones and Thyroid Function

Hormonal systems are designed to respond to extremely small signals. Tiny changes in hormone concentration, receptor sensitivity, or feedback timing can produce significant physiological effects. This precision allows hormones to coordinate metabolism, reproduction, mood, immune activity, and stress response—but it also makes them uniquely vulnerable to disruption.

Environmental toxins exploit this vulnerability.

Rather than damaging tissue outright, many modern chemicals interfere with how hormonal messages are sent, received, and interpreted. The result is often dysfunction without obvious laboratory abnormalities—symptoms without a clear explanation on standard testing.

How Endocrine Disrupting Chemicals (EDCs) Affect Hormone Signaling

One of the primary ways toxins disrupt hormonal function is through endocrine-disrupting chemicals (EDCs). These compounds do not behave like classic poisons. Instead, they interfere with hormone signaling at multiple regulatory levels.

EDCs alter hormonal regulation through several overlapping mechanisms:

Hormone mimicry

Some chemicals resemble estrogen, thyroid hormone, or other signaling molecules closely enough to bind hormone receptors, delivering weak or distorted signals that override normal regulation.Receptor interference

Other compounds block hormone receptors, preventing hormones from exerting their intended effects even when circulating levels appear adequate.Altered synthesis and conversion

Certain toxins interfere with enzymes responsible for producing hormones or converting them into their active forms—particularly relevant for thyroid and steroid hormones.Disrupted central signaling

The hypothalamus and pituitary coordinate hormonal output through feedback loops. Environmental toxins can distort this signaling, leading to inappropriate hormonal responses over time.

Collectively, these effects contribute to hormone resistance at the tissue level—a state in which hormones are present in circulation but ineffective where they are needed most (7).

Clinically, this explains a familiar and frustrating pattern:

laboratory values within reference ranges

persistent hormone-related symptoms

limited or inconsistent response to standard hormone-based treatments

The issue is often not hormone production. It is signal integrity.

→ Endocrine Disruptors Explained: How Everyday Chemicals Affect Hormone Health

Why the Thyroid Is Highly Vulnerable to Environmental Toxins

Among endocrine organs, the thyroid is one of the most sensitive to toxic burden because its function depends on multiple tightly coordinated processes, each of which can be disrupted by environmental exposure.

Normal thyroid activity requires:

adequate iodine uptake into thyroid tissue

selenium-dependent enzymes to convert T4 into active T3

intact liver and gut function for hormone transport and conversion

sufficient mitochondrial energy production to support hormone synthesis and cellular response

Environmental toxins can interfere at several of these points simultaneously. Some inhibit iodine transport. Others impair selenium-dependent enzymes. Many disrupt liver and gut pathways critical for hormone conversion and clearance. Still others impair mitochondrial energy production, reducing cellular responsiveness to thyroid hormone (8).

Because these disruptions often occur downstream of hormone production, standard screening tests may fail to reflect the problem. Patients may be told their thyroid is “normal” while experiencing fatigue, cold intolerance, weight resistance, hair thinning, mood changes, or exercise intolerance.

For this reason, thyroid dysfunction is one of the most common—and most frequently underrecognized—manifestations of chronic toxic burden.

Why Toxic Burden Disrupting Hormones and Thyroid Function Matters Clinically

When environmental toxins disrupt hormone and thyroid signaling, downstream effects ripple through nearly every regulatory system in the body. Metabolism slows. Stress tolerance declines. Immune balance shifts. Inflammation increases. Energy production becomes inefficient.

Understanding this relationship helps explain why hormone-related symptoms often coexist with fatigue, brain fog, autoimmune patterns, and chronic inflammatory conditions—and why reducing toxic burden is frequently a prerequisite for restoring stable hormone and thyroid function.

How Environmental Toxins Contribute to Chronic Disease at the Cellular Level

Chronic disease rarely begins at the organ level. It begins at the cellular level, where energy production, immune signaling, and detoxification processes intersect. Environmental toxins exert much of their damage not by causing immediate injury, but by eroding cellular resilience over time.

Three interrelated mechanisms are especially important.

Mitochondrial Dysfunction Caused by Environmental Toxins

Mitochondria are responsible for producing ATP—the energy currency required for every active process in the body, including detoxification, hormone signaling, immune regulation, and tissue repair.

Many environmental toxins interfere directly with mitochondrial enzymes or indirectly increase oxidative stress within the cell. This combination reduces ATP production while increasing cellular damage (9).

Clinically, mitochondrial suppression presents as:

persistent fatigue that is not relieved by rest

exercise intolerance or delayed recovery

brain fog and reduced cognitive endurance

heightened sensitivity to stress, illness, or sleep disruption

Because mitochondria regulate far more than energy alone, their dysfunction often precedes and amplifies other forms of chronic illness. When cells cannot generate adequate energy, regulatory systems shift into conservation mode—slowing metabolism, impairing hormone responsiveness, and prioritizing survival over repair.

How Toxins Trigger Immune Dysregulation and Chronic Inflammation

The immune system is highly responsive to environmental signals. Chronic toxin exposure promotes a state of persistent, low-grade immune activation, even in the absence of infection.

This occurs through multiple pathways, including:

increased inflammatory cytokine signaling

mast cell activation and histamine release

disruption of immune tolerance mechanisms

Over time, this pattern shifts the immune system away from balanced surveillance toward chronic reactivity (10).

Clinically, immune dysregulation may appear as:

autoimmune or inflammatory conditions

allergic symptoms or chemical sensitivities

food reactions that evolve over time

exaggerated responses to stress, illness, or environmental triggers

Rather than a single immune disorder, patients often experience overlapping immune symptoms that do not fit neatly into one diagnostic category.

Nutrient Depletion and Impaired Detox Pathways from Toxic Burden

Detoxification is tightly linked to nutrient availability. Amino acids, minerals, antioxidants, and B vitamins are required at multiple stages of toxin neutralization and elimination.

As toxin load increases, demand for these nutrients rises. When intake, absorption, or recycling cannot keep pace, detox pathways become progressively less efficient. This inefficiency allows toxins to persist longer, further increasing oxidative stress and nutrient depletion (11).

The result is a self-reinforcing feedback loop:

rising toxic burden increases detox demand

increased demand depletes critical nutrients

depleted nutrients reduce detox capacity

reduced capacity allows toxins to accumulate further

Standard care often misses this cycle because routine testing may show “normal” organ function while cellular resilience continues to decline.

Why This Cellular Perspective Matters

When mitochondrial energy production, immune regulation, and detoxification capacity are simultaneously compromised, the body adapts by altering function rather than failing outright. These adaptations—fatigue, hormone resistance, inflammation, heightened sensitivity—are often labeled as separate conditions rather than recognized as expressions of the same underlying strain.

Understanding toxin-driven cellular dysfunction helps explain why chronic illness is frequently multisystem, fluctuating, and resistant to isolated, symptom-based interventions.

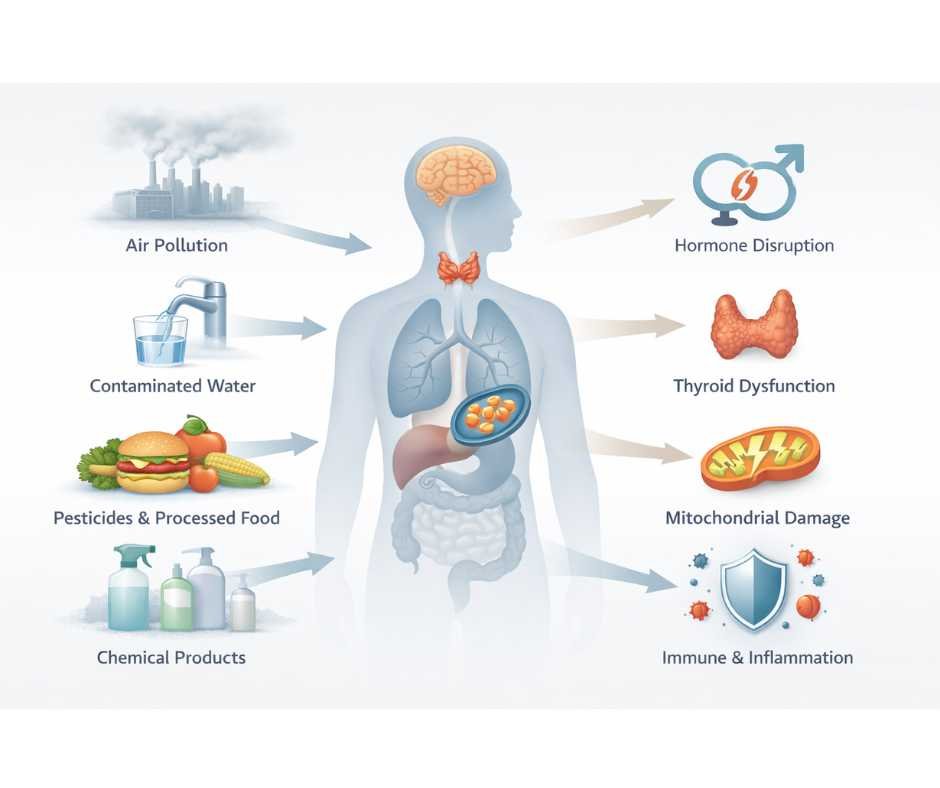

Major Sources of Environmental Toxins: Food, Water, Household Products, and Air

Although toxins are often discussed as isolated threats, the body does not experience them that way.

From a physiological standpoint, food, water, household products, air, and metals all converge on the same core systems: detoxification pathways, hormonal signaling, immune regulation, and cellular energy production. What differs is how each category enters the body, where it accumulates, and which systems are stressed first.

Understanding these distinctions is essential for recognizing exposure patterns and reducing toxic burden strategically rather than reactively.

Food-Based Environmental Toxins and Daily Dietary Exposure

Food represents one of the most consistent sources of toxic exposure because it is consumed daily and in volume. Even individuals who eat “clean” or organic diets may be exposed through agricultural practices, processing, packaging, and environmental contamination.

Food-based toxins are particularly impactful because they:

interact directly with gut and liver detox pathways

influence bile flow and elimination

affect the microbiome and intestinal barrier

contribute to systemic inflammation when clearance is impaired

Over time, repeated dietary exposure can quietly tax detox capacity and alter metabolic and hormonal regulation.

→ Hidden Toxins in Food Labels: How to Identify Harmful Ingredients (Part 1)

→ The Dark Side of Food Processing & Engineering (Part 2)

→ The Hidden Dangers of CAFO-Raised Meat & Emerging Food Alternatives (Part 3)

→ When Good Food Gets Contaminated: Hidden Toxins from Farming, Industry, and the Environment (Part 4)

→ How to Avoid Hidden Toxins in Food: Source Clean Ingredients, Shop Smarter, and Eat Safer (Part 6)

Drinking Water Contaminants and Hidden Daily Chemical Exposure

Water is unique among toxin sources because it is consumed multiple times per day and is rarely questioned. Many contaminants are odorless, tasteless, and invisible, allowing exposure to continue unnoticed for years.

Water-based toxins:

enter circulation rapidly

compound daily exposure load

bypass many of the “protective pauses” that occur with food

Even low concentrations can become clinically meaningful due to frequency and cumulative dose.

→ Is Your Drinking Water Safe? The Truth About Hidden Contaminants (Part 5)

Household and Personal Care Toxins That Disrupt Hormones

Household and personal care products represent one of the most underestimated toxin categories. Chemicals absorbed through the skin or inhaled indoors enter circulation without first-pass liver detoxification, placing immediate demand on systemic clearance pathways.

These exposures disproportionately affect:

hormonal signaling

nervous system regulation

immune reactivity

Because they are part of daily routines, they often persist even when diet and supplementation are optimized.

→ Hidden Toxins in Household Products & Your Environment

Heavy Metal Toxicity and Bioaccumulative Environmental Stress

Heavy metals differ from many organic chemicals in that they do not break down or metabolize efficiently. Instead, they accumulate in tissues and interfere directly with enzymes, mitochondria, and neurological signaling.

Heavy metal exposure:

compounds effects of other toxins

increases oxidative stress

impairs detox enzyme function

disproportionately affects thyroid and nervous system regulation

Because accumulation is gradual, symptoms are often delayed and nonspecific.

→ Heavy Metal Toxicity: The Hidden Threat Lurking in Your Food, Water, and Environment

Indoor Environmental Toxins: Mold, Mycotoxins, and Airborne Chemicals

Indoor environmental exposures represent another major—but often overlooked—source of toxic burden. Water-damaged buildings can harbor mold and mycotoxins that enter the body through inhalation and direct contact, placing sustained strain on immune regulation, mitochondrial energy production, and detoxification pathways. Unlike many dietary exposures, these toxins are encountered continuously and may persist even when diet and lifestyle are optimized.

→ Is Mold Toxicity Making You Sick? Hidden Symptoms, Mycotoxins, and How to Detox Safely

Detoxification Pathways Explained: What Determines Your Ability to Handle Toxic Exposure

Detoxification capacity determines how effectively the body can process, neutralize, and eliminate environmental exposures.

Every person encounters toxins through food, water, air, and daily contact with household materials. What differs is how well the body can manage that load. Detoxification capacity determines whether ongoing exposure remains tolerable or becomes physiologically disruptive. When capacity is reduced, even relatively modest inputs may trigger symptoms.

This distinction helps explain why two individuals with similar diets, environments, or lifestyles can experience very different health outcomes. In many cases, the issue is not exposure alone, but whether the systems responsible for clearance and recovery are functioning within their limits.

→ Detox Done Right: A Comprehensive Guide to Safe and Effective Detoxification

Why Toxic Burden Is Cumulative: How Multiple Exposures Overload the Same Systems

In clinical practice, toxic burden is rarely attributable to a single source. More often, it reflects simultaneous exposure across multiple domains, layered onto a background of limited detoxification capacity.

Food, water, household products, air, and materials do not act independently. Their effects converge on the same regulatory systems—hormonal signaling, immune balance, detoxification pathways, and cellular energy production. When these systems are already under strain, additional inputs that might otherwise be tolerated can become symptomatic.

This is why isolated interventions—addressing diet alone, focusing on supplements alone, or attempting standalone detox strategies—often lead to partial or short-lived improvement. Durable progress depends on recognizing how exposures interact, identifying which inputs are exerting the greatest load, and reducing burden in a way that aligns with the body’s current capacity.

Why Environmental Toxin Exposure and Toxic Burden Are Often Missed in Conventional Medicine

Toxic burden is rarely identified in conventional medical settings—not because it lacks evidence, but because it does not align with how modern medicine is structured.

Conventional evaluation is optimized to detect discrete disease states: a failing organ, a clearly abnormal lab value, or a defined pathology. This approach is effective for acute illness and advanced disease, but far less effective for identifying gradual, multisystem strain that develops over time.

Most routine testing asks a narrow question: Is this value inside or outside a reference range today?

It does not assess whether regulatory systems are maintaining function under increasing physiological load.

Environmental toxin exposure and toxic burden primarily affect regulatory systems rather than isolated organs. Hormonal signaling, immune balance, mitochondrial energy production, and detoxification capacity may all be strained simultaneously while standard labs remain within reference ranges. As a result, exposure history, cumulative load, and clearance capacity are often overlooked.

Symptoms affecting multiple systems are then evaluated in isolation. Fatigue is attributed to stress or sleep. Hormonal symptoms are treated as gland-level issues. Brain fog is framed as mood, attention, or aging. The shared upstream driver—systemic toxic load—remains unrecognized.

The result is a familiar clinical pattern: persistent symptoms, reassuring test results, and treatment strategies that manage surface findings without addressing the underlying strain.

Cumulative Environmental Toxin Exposure Is Rarely Evaluated in Standard Care

In conventional care, patients are rarely asked detailed questions about food sourcing, drinking water quality, household and personal care products, occupational exposures, or long-term environmental history. Without this context, chemical exposure remains largely invisible in the clinical record—even when it is biologically significant.

From a medical standpoint, what is not measured is often treated as irrelevant.

Why Detoxification Pathways Are Rarely Assessed in Conventional Medicine

When liver enzymes fall within reference ranges, detoxification is often presumed to be adequate. In reality, toxin neutralization and elimination depend on far more than liver enzymes alone. Nutrient availability, gut integrity, bile flow, mitochondrial energy production, antioxidant reserves, and lymphatic clearance all influence how effectively the body can manage chemical load.

These dimensions of function are rarely evaluated in routine care, yet they play a significant role in symptom development and recovery capacity.

Why Multisystem Symptoms Are Treated in Isolation Instead of Root Cause

When physiological systems are evaluated separately, symptoms are often siloed. Fatigue is attributed to sleep or stress. Hormonal symptoms are treated as gland-level issues. Brain fog is framed as mood, attention, or aging. Each presentation is managed independently, while the shared upstream driver—systemic toxic load—remains unrecognized.

This fragmented approach frequently leads to sequential or overlapping treatments that address surface manifestations without resolving the underlying strain.

The Clinical Consequences of Missing Toxic Burden

When toxic burden is not considered, toxin-driven physiology is frequently mislabeled as:

stress or burnout

normal aging

idiopathic fatigue

unexplained hormone imbalance

“functional” symptoms without a clear cause (17)

Patients are often told their labs are “normal” while their lived experience steadily worsens. Management becomes symptom-focused rather than capacity-focused, and the cumulative burden continues to build.

Understanding this gap is essential—not to assign blame, but to explain why so many people feel unwell without a clear diagnosis, and why a systems-based framework is often required to make sense of complex, chronic symptoms.

How Functional Medicine Evaluates and Treats Toxic Burden

A functional medicine approach begins with a different clinical question.

Rather than asking, “What diagnosis does this fit?” it asks:

“What combination of exposures and physiological demands is exceeding this person’s capacity to regulate, adapt, and recover?”

From this perspective, symptoms are not random failures or isolated malfunctions. They are signals—evidence that one or more regulatory systems are under sustained strain. Toxic load is evaluated not as a stand-alone problem, but as a force that interacts with nutrition, stress physiology, gut function, hormonal signaling, immune balance, and cellular energy production.

At Denver Sports & Holistic Medicine, toxin-related care is sequenced, individualized, and intentionally conservative. The clinical priority is not to initiate detoxification prematurely, but to understand why detoxification has become difficult or destabilizing in the first place.

This approach is guided by three core clinical principles.

Why Detox Capacity Must Be Supported Before Mobilizing Toxins

Detoxification places significant demand on the body. Mobilizing stored toxins increases the need for ATP, antioxidants, bile flow, gut elimination, kidney filtration, and lymphatic movement.

Before attempting clearance, we assess whether the body has sufficient capacity to tolerate that demand. This includes evaluating energy availability, nutrient reserves, digestive and eliminative function, oxidative balance, and nervous system stability.

When clearance is pursued without adequate capacity, patients often experience worsening fatigue, headaches, anxiety, inflammation, or hormonal symptoms. These reactions are not “die-off” in a therapeutic sense—they are signs that the system is being pushed beyond its current resilience.

Reducing Ongoing Toxin Exposure as First-Line Therapy

One of the most underestimated interventions in toxin-related illness is reducing incoming exposure.

Improving food sourcing, water quality, indoor air, and household product use can significantly lower toxic burden without stressing detox pathways at all. For many patients, these changes alone lead to noticeable improvements in energy, sleep, mood, hormone stability, and inflammatory symptoms.

This step is often more impactful—and safer—than supplements or protocols, particularly in individuals with fragile energy reserves or heightened sensitivity.

Why Detoxification Must Be Gradual and Clinically Sequenced

When detoxification is appropriate, it is supported gradually and in phases, aligned with the patient’s overall physiological state. Timing matters. So does sequencing.

Effective detoxification accounts for:

nervous system regulation

hormonal context

metabolic stability

immune reactivity

elimination capacity

The goal is not to force clearance, but to restore regulatory balance so detoxification can occur naturally and sustainably.

→ Detoxification & Environmental Medicine

Testing and clinical assessment are used to clarify exposure patterns, identify limiting factors, and guide decisions about when—and how—to intervene. This prevents unnecessary protocols and reduces the risk of destabilization.

The objective is not aggressive detoxification. It is restoring resilience, so hormonal, metabolic, immune, and neurological systems can stabilize and function effectively again (18).

When exposure decreases and capacity improves, the body often does far more of the healing work on its own than patients expect.

Signs You May Need Evaluation for Toxic Burden or Environmental Illness

Lifestyle changes—such as improving diet, reducing stress, and optimizing sleep—are often meaningful first steps. However, when symptoms persist or recur despite these efforts, it suggests that underlying physiological strain has not been fully addressed.

Deeper evaluation may be appropriate if you are experiencing patterns such as:

fatigue that does not resolve with rest or improved sleep

hormone-related symptoms that persist despite “normal” lab results

thyroid symptoms with limited or inconsistent response to standard treatment

increasing sensitivity to foods, chemicals, or environmental exposures

inflammatory or immune symptoms that fluctuate without a clear trigger

symptom worsening during stress, illness, weight loss, or lifestyle changes intended to improve health

These patterns often indicate that regulatory systems—energy production, detoxification, immune balance, and hormonal signaling—are operating near their limits. In such cases, addressing surface-level inputs alone may not be sufficient.

A systems-based evaluation focuses on identifying what is exceeding capacity, rather than chasing individual symptoms in isolation. This allows care to be targeted, sequenced, and supportive rather than reactive.

Persistent fatigue, hormone instability, thyroid symptoms, or chronic inflammation with “normal” labs may reflect toxic burden rather than isolated dysfunction.

You may request a free 15-minute consultation with Dr. Martina Sturm to review your health concerns and outline appropriate next steps within a root-cause, systems-based framework.

The goal is clarity—not assumptions—and a path forward that aligns with how your body is actually functioning.

Key Clinical Insights on Toxic Burden and Hormone Dysfunction

Toxic burden develops gradually through cumulative environmental toxin exposure.

Hormonal and thyroid systems are highly sensitive to regulatory disruption.

Normal laboratory ranges do not rule out toxin-driven dysfunction.

Detoxification requires sufficient energy, nutrients, and proper sequencing.

Reducing ongoing environmental exposure is often the most impactful first step.

Frequently Asked Questions About Toxic Burden and Environmental Exposure

What is toxic burden, and how does it affect health over time?

Toxic burden refers to the cumulative chemical load the body carries relative to its ability to neutralize and eliminate those substances. It develops gradually through repeated low-dose exposure from food, water, air, and everyday products. When cumulative exposure exceeds detoxification and regulatory capacity, the body adapts by altering function—often contributing to fatigue, hormone resistance, thyroid dysfunction, inflammation, and reduced resilience over time.

Can toxins cause hormone symptoms even if my labs are normal?

Yes. Many environmental chemicals disrupt hormone signaling rather than hormone production. They may interfere with hormone receptors, cellular uptake, or feedback loops between the brain and endocrine glands. In these cases, blood hormone levels can appear normal while tissues fail to respond appropriately, leading to persistent symptoms despite reassuring lab results.

Why is the thyroid especially vulnerable to toxic exposure?

The thyroid depends on tightly coordinated processes including iodine transport, selenium-dependent enzyme activity, liver and gut conversion, and adequate cellular energy. Environmental toxins can interfere at multiple points simultaneously. Because many disruptions occur downstream of hormone production, standard screening tests may not reflect the underlying dysfunction until symptoms are well established.

Can detox cleanses or fasts safely reduce toxic burden?

Not always. Detoxification is a biochemical process, not a cleanse. Aggressive detox programs or prolonged fasting can mobilize stored toxins faster than the body can safely eliminate them—especially in individuals with low energy reserves, nutrient deficiencies, or hormonal instability. This can worsen fatigue, inflammation, anxiety, or hormone symptoms rather than improving them. Effective detoxification prioritizes capacity, sequencing, and support over intensity.

Is toxic burden reversible?

In many cases, yes—particularly when addressed early and strategically. Reducing ongoing exposure, restoring nutrient sufficiency, supporting detoxification capacity, and stabilizing energy and immune regulation can allow the body to regain function over time. Improvement is typically gradual, with increased resilience and symptom stability often preceding full resolution.

Still Have Questions?

If the topics above reflect ongoing symptoms or unanswered concerns, a brief conversation can help clarify whether a root-cause approach is appropriate.

Resources

Endocrine Society – Endocrine-Disrupting Chemicals

WHO – Chemical Exposure and Chronic Disease

NIH – Human Detoxification Pathways

Environmental Health Perspectives – Chronic Low-Dose Chemical Exposure

NIEHS – Hormones and Environmental Chemicals

Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism – Endocrine Disruption

American Thyroid Association – Environmental Influences on Thyroid Health

Frontiers in Endocrinology – Thyroid Hormone Disruption

Cell Metabolism – Mitochondrial Toxicity

Journal of Immunology – Environmental Immune Dysregulation

Nutrients – Detoxification and Micronutrient Depletion

FAO – Food Contaminants and Health

EPA – Drinking Water Contaminants

Environmental Research – Dermal Chemical Absorption

Toxicology Letters – Heavy Metal Bioaccumulation

Clinical Toxicology – Risks of Improper Detox

Lancet Planetary Health – Environmental Disease Burden

Functional Medicine Research Center – Personalized Detoxification